On the way to Moratuwa from Piliyandala, you cross the Bolgoda Bridge, where the path bifurcates between the road to Katubedda on your right, and the road to Rawathawaththa on your left. The road to Rawaththawaththa is smaller and more crowded: you pass countless furniture shops, fruit and vegetable stalls, a few fishmongers, some grocery stores and a church and a temple, before winding up at a small suburb which forks into several small lanes.

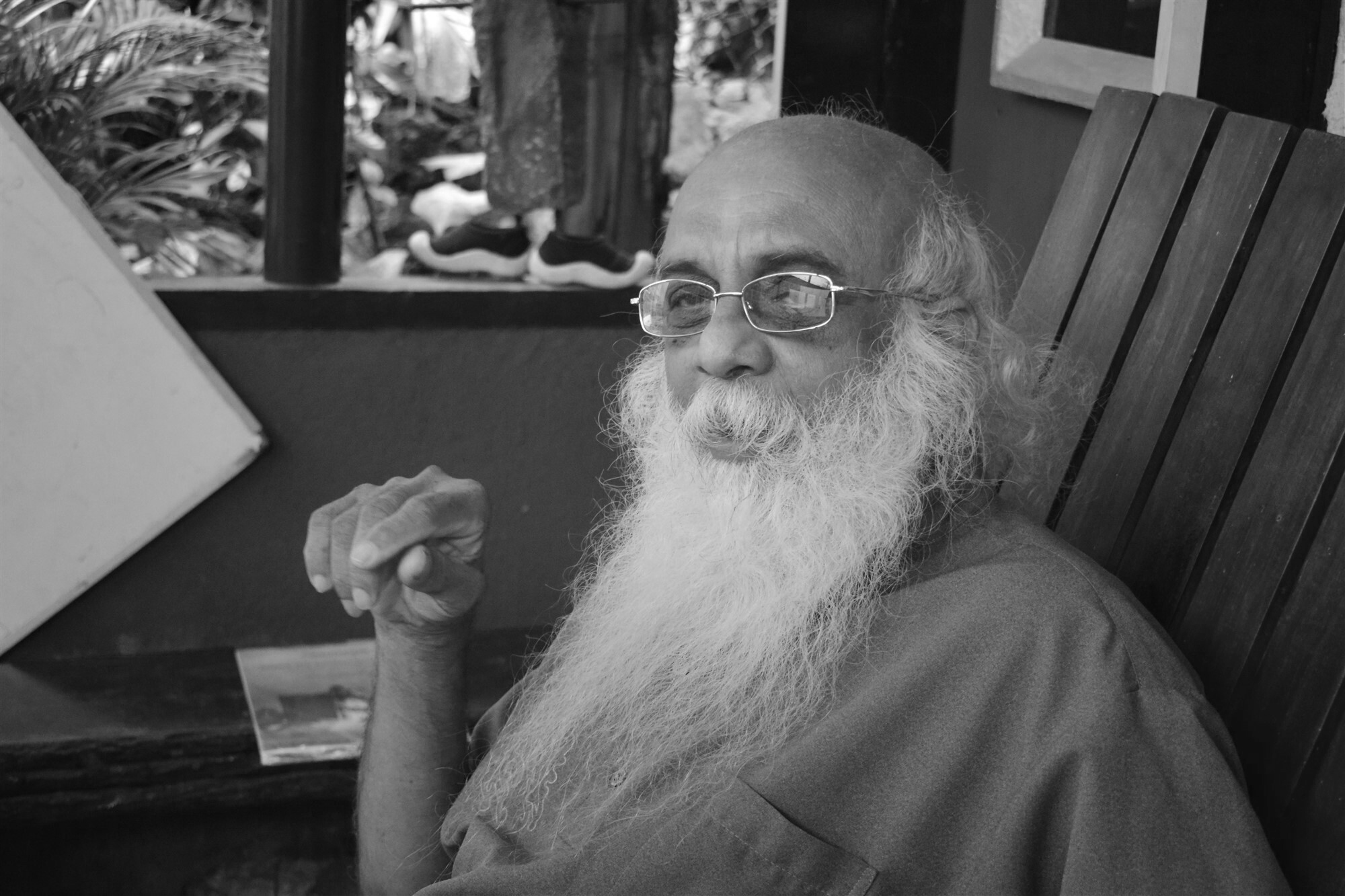

This is where Givantha Arthasad lives.

Initially, the maze of lanes that lead to his house made it difficult for me to locate him. Once I found it, however, all the other houses seemed to vanish before me; his one looked like it stood a world or two apart.

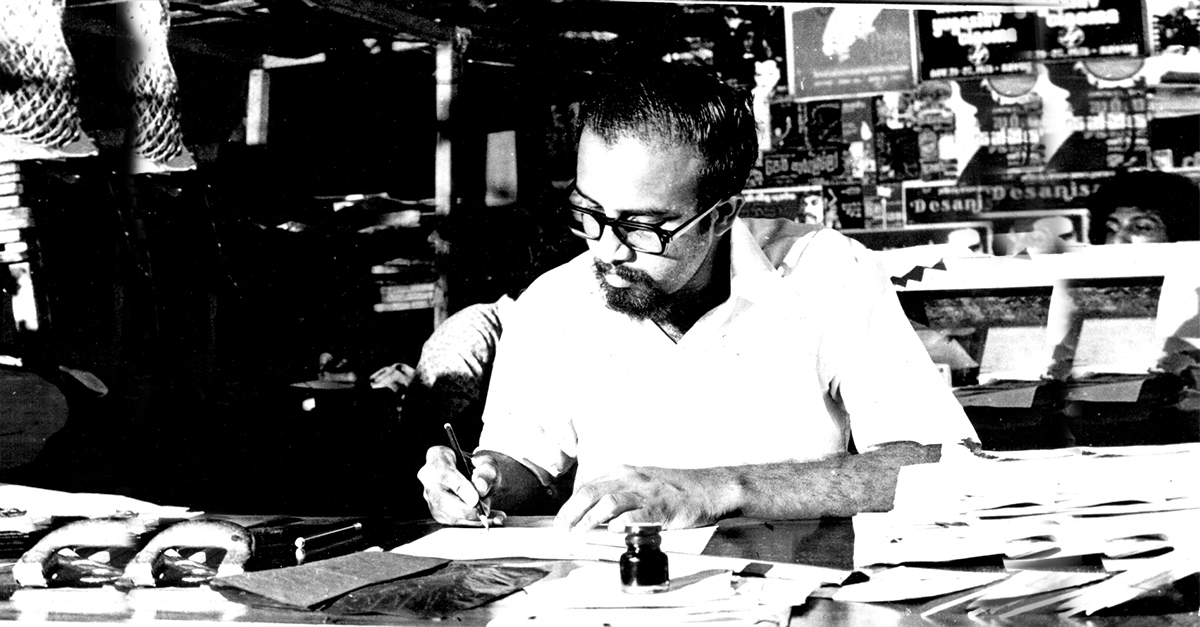

A series of steps lead to a low elevation, with shrubs and bushes flanking either side. The veranda, where we sat, was adorned with craftwork and designs, including paintings and clay figures that I could only look upon with awe.

Arthasad calls himself an artist. Of what kind though? Diplomatically, he refrains from answering. For someone who has led so many lives—as a graphic designer, painter, photographer and dramatist, working in cinema, television, broadcasting, and journalism—the word “artist” hardly captures his versatility, especially since his contributions surpass anything a crass generalisation of that sort can lead us to assume.

This is his story.

Early Years

Arthasad was born Baminihennedige Givantha Arthasad Peiris to religiously devout parents in Katunayake, both of whom were involved in education. His father, George A. Peiris, was the Scout Commissioner of Sri Lanka and his mother, Dulcie Peiris, worked as a teacher. “I attended Methodist College in my hometown, where my father served as principal, before being sent to Wesley College in Colombo from Grade Two,” he told me.

Arthasad inherited his artistic capabilities from his parents. “My mother used to bring children from our neighbourhood to our home, where she taught them to make toys, sculpt, and paint—for free. Naturally, she taught me too,” he said. His father, on the other hand, taught him to “read newspapers upside down, and to read aloud, paying close attention to the dramatic nuances of a passage.”

With these early encounters, he moved on to Wesley, where his Grade One class teacher was so impressed by his painting skills he had once remarked, “You shouldn’t have been born in a country like this.” That class teacher was Cyril Wickramage, later a renowned, award-winning actor. And he wasn’t the only staff member to encourage young Arthasad’s talent. “My Grade Three class teacher, Mrs Ivy Marasinghe would conduct art classes after school, which my friends and I helped her with. During weekends she took us to watch cartoons. That’s where I encountered the world of animation, from Mickey Mouse to Donald Duck,” he explained.

Surprisingly, for someone who loved to draw, young Arthasad opted to take science at Wesley. This was to become a problem when his studies clashed with his desire to paint and submit his work to various art competitions. “The principal at Wesley, the educationist Shelton Wirasinha, who had to sign off on my work before submission, would always say something to the tune of ‘Putha, we can’t do this every day, it would be better if you chose art’,” Arthasad said.

Not even that he was entirely removed from science: In fact, physics was one of his favourite subjects and as he progressed, he eventually graduated from geometry to mechanical drawing.

“I can’t say these didn’t influence my career,” he said. “When we draw, the foundation for our work is the line and the circle. No matter what those who try to divide art and science say, there will always be a scientific aspect to drawing. I realised this very early on.”

Still, he confesses, “Mr Wirasinha’s prodding led me to wonder whether I ought to be studying science instead.” Eventually, with the intervention of Wirasinha and Jayantha Premachandra,head of the Arts Section, Arthasad moved from the science stream to the arts stream. How did the elders in his family take it? “My father had wanted me to become a parson due to a promise they’d made to God after the death of my elder brother,” he said, but they gave in to my wishes. After my O/Levels, they allowed me to do what I pleased.”

Finding His Calling

One of the very first problems Arthasad faced in his career was that no institution taught what he wanted to pursue: the performing arts. “The only place I could go to was the Heywood Institute (now the University of Visual and Performing Arts),” he said. “But Heywood taught music. I realised soon that it wasn’t my cup of tea, so I decided to teach myself.” Arthasad said he reckoned an opportunity would come his way sooner or later, and as anticipated, an opportunity did come, much sooner than he’d expected.

Linus Dissanayake, a doctor turned film producer, had started a small but prominent studio called ‘Dissanayake Studios’, which had bankrolled Professor Siri Gunasinghe’s groundbreaking film ‘Sath Samudura’ in 1967, which featured a breakthrough performance by Arthasad’s Grade One class teacher at Wesley, Cyril Wickramage. Three years later the studio financed another landmark production, Vasantha Obeyesekere’s ‘Wes Gaththo’, also starring Cyril.

By the time of Wes Gaththo’s release, Arthasad had come into contact with Dissanayake, “from whom I borrowed a camera and went on to make a short animated sketch on Andare,” he said. The Film Critics’ and Journalists’ Association nominated it for their annual Short Film Festival in 1971, where it competed with Sunil Ariyaratne’s ‘Sara Gee’and Dharmasena Pathiraja’s ‘Sathuro’.”

Arthasad’s next destination was Ceylon Theatres, where, thanks to his friendship with the comedian and singer Freddie Silva, he made contact with Derrick Fernando, who worked as an official there, and Titus Thotawatte, who taught him filmmaking and also introduced him to Andrew Jayamanne, who taught him cinematography.

He had by then made another animated short film, ‘Muhuda Yatin Ira Payayi’, which won for him a Jury Prize from the Film Critics’ and Journalists’ Association in 1972. His third attempt, seven years later, would leave a much larger imprint on the cinema.

The ‘Dutugemunu’ Episode

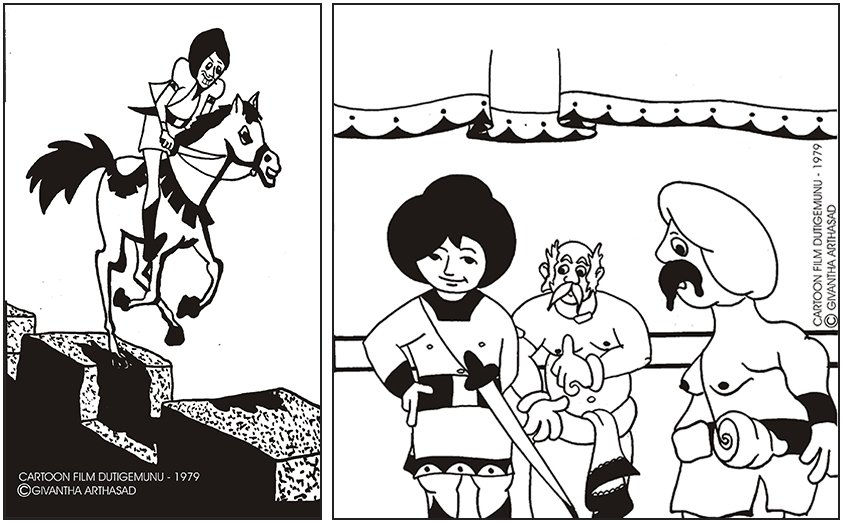

That third film, ‘Dutugemunu’, was not well received by officials at the time of its release in October 1979, although according to Arthasad, the few ordinary people who saw it were thrilled by it. Based on an important episode from Sri Lankan history, its charm lay in the dazzlingly novel way it presented an otherwise serious subject.

“I didn’t follow a conventional narrative,” Arthasad told me. “Instead of relating the story of the hero, I started with an unlikely beginning: a cat visiting the Ruwanwelisaya Dagoba with its kittens, who want to know the story behind its construction. From there, the film relates the Mahavamsa version of events. The cat figures in those events because in one of its previous births, it had served as Dutugemunu’s purohita or chaplain.

With a prominent cast, including influential figures from Arthasad’s own childhood—Wickramage voiced the eponymous hero, while Felix Premawardhana, a stage actor who’d taught literature at Wesley, voiced his main soldier, Nandimitra), Dutugemunu the film focused on the hero’s search for the ‘dasa maha yodhayo’ (ten giant warriors) for his battle against Elara or Ellalan, a member of the South Indian Chola dynasty, who ruled as the King of Sri Lanka’s Anuradhapura Kingdom from 205 BCE to 161 BCE. With the renowned Sri Lankan playwright Henry Jayasena voicing Dutugemunu’s father, Kavantissa, and Arthasad voicing various other characters, the animated film was tipped to be a watershed. As things turned out though, “audiences barely noticed it.”

The issue wasn’t with the audiences, however, but with political authorities. In 1977, the United National Party (UNP) had come to power promising, on the one hand, a dharmista samajayak or a “righteous society”, and on the other, ethnic coexistence.

“Certain educationists thought the story of Dutugemunu was not amenable to coexistence, given the racialist overtones of his triumph over Elara. They made a complaint to the Education Ministry, which excised the story from textbooks and imposed a ban on any form of propagating it. That is why I was forced to take out my film right after I’d released it,” Arthasad said.

A tragedy, because the film didn’t carry a racist message – “It was entertainment for kids based on Westerns like ‘The Magnificent Seven’” Arthasad said, explaining also that he had toiled to make his characters—including the sunglass-wearing cat that takes us through history—come alive on screen.

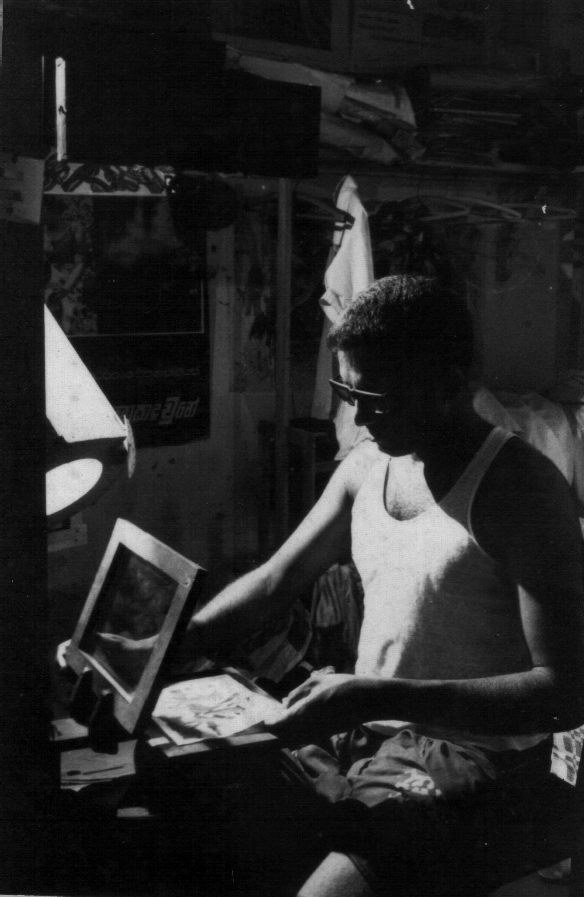

How hard had he toiled, really, considering that this was produced at a time when digital cinema remained, even in the West, a distant dream? “I had to insert India ink on every frame,” Arthasad said. “In each of my first two films I used more than a thousand such frames. Dutugemunu used more than that. You can imagine the concentration I had to put into these efforts!”

Mercifully, he didn’t have to suffer a financial loss due to the ban. Far from it, in fact: With the compensation he received from authorities after they ordered theatres to stop screening his film, he was able to buy the house he currently lives in.

Television And Stamp Designing

Controversy over Dutugemunu notwithstanding, Arthasad proceeded to the next phase of his career. It had only been six months before that television had made its entry to the country, and the following year Arthasad was sent to study television in Berlin. On his return, he was first posted to the Animation Division of the Sri Lanka Rupavahini Corporation (SLRC), but later worked in other divisions as well.

In 1987, two years after he discovered his eyesight was failing him, he gave in his resignation to Rupavahini. “I was told my retina had been damaged, and that I’d lose my sight in a few years. I was then told that I would have to live with God. Well, God has been merciful to me. I can see clearly even now!,” he said.

It was around that time that Arthasad discovered a new career: stamp designing. On the wall of his veranda is a huge poster displaying his most prominent designs, which include the 150th anniversary stamp of Royal College and a stamp issued to celebrate the opening of the Victoria Dam. Once again, in a pre-digital era, “drawing these wasn’t the easiest thing to do,” Arthasad said. For the Victoria Dam stamp, for instance, he had to personally visit and survey the site, just to come up with a miniature graphical representation of it.

Further Work in Animation

In 2001, 22 years after Dutugemunu was released, Arthasad made Sri Lanka’s first digitally animated film: ‘Mahadana Muththayi Golayo Roththayi’. Due to the then ongoing war, however, it too passed by unnoticed, though on those who saw it—including an eight year old me—it made a favourable impression. It certainly made an impression on the International Catholic Organization for Cinema (OCIC). At the 28th OCIC and UNDA (or International Catholic Association for Radio and Television) Awards Ceremony the following year, it won a Special Jury Prize.

Last year, Arthasad screened his third feature film, ‘Eureka’, but to a limited audience of dignitaries and journalists. This film still has not been released and the larger public is still agog with anticipation. What little we know can be summed up in Arthasad’s own words—“it is an “experimental film, probably the first of its kind in Sri Lanka.” Only time will tell if the film, as a whole, stands up to such an estimation. Until then, we can only wait.