What comes to your mind when you remember media reports of rape and suicide? Photographs of the victims, including their names? Gruesome details of how it happened, along with quotes from the family?

The photographs and names might help to ‘humanise’ the story a bit, but it is also a massive violation of the victim’s—and the family’s—privacy. Publishing these details could also lead to stigmatisation, impeding the survivors’ recovery.

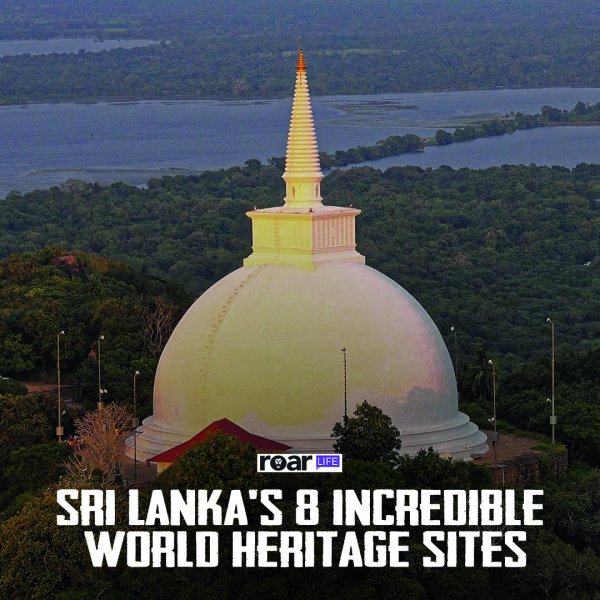

In February, Duncan Macmillan’s one-man show “Every Brilliant Thing” was performed in Sri Lanka. Both humorous and poignant, the play told the story of a man living in the shadow of his mother’s suicide—while also touching on how it should be addressed by the media.

A broadway hit, a review by Mitchell Miller, from Willamette Week runs through guidelines newspapers ought to follow through when reporting on suicide.

“…never describe the method used, don’t assume motivation from recent life events, don’t use the word ‘commit’ in reference to the action, never describe an attempt as ‘successful’. ‘Suicide is contagious, says Lamb, who plays the one-man show’s unnamed character. One suicide can often lead to more suicides in densely populated areas, he explains, citing the Goethe novel The Sorrows of Young Werther. Toward the end of the play, he adds, ‘There’s one thing you should know if you’re considering suicide: don’t do it.’”

Is Suicide Contagious?

Not only does this play address topics like suicide and depression, it also reminds the media of how they ought to report these incidents. Image courtesy: pcs.org

Focusing on the life of a man with a suicidal mother, the lead character emphasises on the statement that suicide is contagious—hence, giving publicity to the act must be done cautiously. For instance, studies in the United States have noted that whenever a popular public figure dies of suicide, there is a jump in the number of suicides in the following months. According to the New York Times, approximately 5% of youth suicides are influenced by other suicides—ergo establishing a link between incident, publicity, and repetition. However, don’t just take our word for it; this is also corroborated in the paper “Media Contagion and Suicide Among the Young”, which notes that:

“Research continues to demonstrate that vulnerable youth are susceptible to the influence of reports and portrayals of suicide in the mass media. The evidence is stronger for the influence of reports in the news media than in fictional formats. However, several studies have found dramatic effects of televised portrayals that have led to increased rates of suicide and suicide attempts using the same methods displayed in the shows. Recent content analyses of newspapers and films in the United States reveal substantial opportunity for exposure to suicide, especially among young victims. One approach to reducing the harmful effects of media portrayals is to educate journalists and media programmers about ways to present suicide so that imitation will be minimized and help-seeking encouraged.”

How Media Monitoring Helps

Verite Research has a media watchdog arm by the name of Ethics Eye. Active on Facebook and Twitter, the organisation keeps tab of unethical reporting by each mainstream media publication, and corrects it online.

Verite’s Head of Media Research Deepanjalie Abeywardana told Roar Media that a significant number of ethics violations have reduced since they started their monitoring campaigns. However, unlike the Press Complaints Commission, Ethics Eye does not engage directly with the media organisations, unless invited to do so.

“We train journalists on how to report ethically on issues if we’re approached. They then practice what they learn, and we see can see that reflected in papers afterward. One of the things we tell them is to not simplify suicide when reporting it. We can’t just say someone hung himself because of a break up, because a suicide is the outcome of a series of complications. It’s not up to the media to conclude the cause of suicide; there are a load of factors,” Abeywardena elaborated.

How Should We Report ‘Sensitive’ News?

Press Complaints Commission of Sri Lanka CEO Sukumar Rockwood. Image courtesy: caffesrilanka.org

The Editors’ Guild of Sri Lanka has a code of professional practice, last revised four years ago. Whether this code is practiced or not is, in most cases, evident in local headlines and news pieces—especially in media organisations which report in the vernacular.

Speaking to Roar Media, Press Complaints Commission of Sri Lanka (PCCSL) CEO Sukumar Rockwood outlined what a media organisation’s responsibility should be.

“When reporting on suicide, care should be given not to go into detail of how the act was performed. For instance, the journalist shouldn’t describe how the person climbed a chair or table, and then used a rope and such. They shouldn’t give methods used in suicide—you can say how they died, but not in detail,” he said.

PCCSL’s annual report for 2016 noted 133 complaints, with most of them from the Sinhala media. Most of these were resolved amicably by editors providing a ‘Right of Readers’, reports say.

It is interesting to note that the mainstream media can publish almost anything they want as there is no monitoring institute which can take action against them. The PCCSL in itself is a voluntary, independent, and self-regulatory body. The commission simply resolves issues by making note of the complaint, and then contacts the editors, Rockwood said.

Speaking further on reporting rape, Rockwood emphasized that absolutely no details (except for the age) of the victim should be published—be it their name, address, or photographs. It’s fine to publish those of the perpetrators once convicted, he added.

Meanwhile, the Poynter Institute has a few more tips on how to report rape, reproduced below:

- Use clear language when reporting on rape. Journalists sometimes slip into the habit of making victims the “actors” as a way of sanitizing the language. We say, for instance, that a young girl “performed an oral sex act,” rather than, “He forced his genitals into her mouth”. Words and sentence structure matter in stories about rape.

- Describe charges of sex without consent as rape, not anything less. While no rational person will suggest that these women were complicit in their ordeal, sometimes writers minimize the trauma of rape by describing it as sex or intercourse if the rape doesn’t involve the kind of physical violence that requires medical attention.

- Be careful about details that could imply you are blaming victims. Describing what a girl was wearing, or how she made a choice, can be perceived as assigning blame.

However, there is a loophole when it comes to victim privacy, Rockwood added.

“We’ve told journalists now that they can publish what comes out in courts…but to please use discretion.”

He also noted that while English newspapers are more careful, the Sinhala and Tamil publications were not. “The problem with Sinhala and Tamil reports is that it comes from correspondents from all corners of the country,” Rockwood said, stating that they were, “not from trained journalists”.

In an attempt to reduce these unethical practices, the PCCSL conducts training programmes for journalists and provincial correspondents. They are also in regular contact with editors of mainstream media organisations. However, the necessity of giving garish detail in vernacular reports need to be monitored and lessened.

Cover credit maxpixel.net