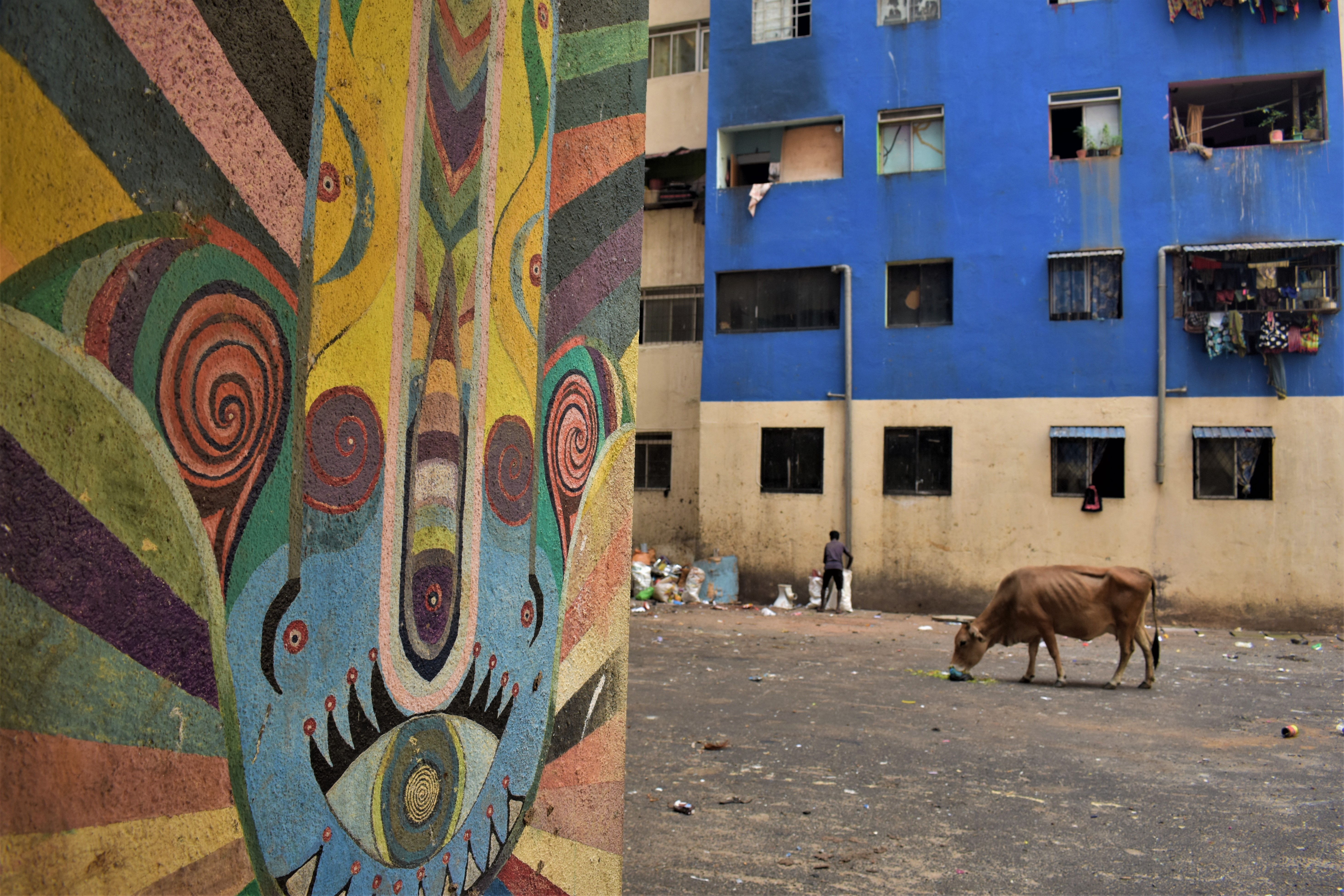

For a person walking the narrow paths of Wanathamulla, the concrete alleyways amidst the high-rise condominiums, the last thing you would expect to find are murals.

The dull drab walls of Sahaspura, housing families in its 430 small apartments, that run up 12 storeys has a common courtyard that has been turned into a garbage dump.

One wall donnes a traditional red and orange yaksha mask with piercing deadly eyes. Alongside it is a half painted sketch of a woman’s face overlaid with a clock. A sketch of Ravana in all his godly regalia is drawn on another wall. Nearby, someone has crudely written කුනු (garbage) on the side.

No one ever goes there to collect the garbage. Scraps and whatnot are thrown out of the condominium windows that fall straight down 12 storeys, it is dangerous enough to maim a person. These walls that have forgotten at least a semblance of fresh paint are decorated in curious murals.

We asked a couple of men, smoking a beedi nearby whether they knew the artist who painted these murals. “Probably some කුඩුකාරයා (drug user),” they responded and told us to go away.

Art As Disruption

Sri Lanka has a vibrant art culture. We have a historic tendency to draw on walls, that go back to the earliest cave paintings to the Sigiriya murals. However, murals and street art remains a dying subculture even in the arts hub of the nation. Yes, we have the one off competition organised by a high profile restaurant chain to paint the walls in a bid to attract a potential market. Other than that it is hard to find artists, who are dedicated to make art for the sake of making art.

Photo credits: Akila Jayawardana

The public perception of making murals is considered a nuisance mostly due to the unwanted graffiti that decorate every other wall with the names of schools and disturbed lovers to the toilet cacography. Many of the residents in Dematagoda and Wanathamulla, did not know who was behind the murals that were found all over the place. Most of them, disregarded them, despite its uniqueness and the obvious story they were telling.

A dirty staircase, covered in betel juice spit stains held Bugs Bunny passing a rolled up cigarette to Mickey Mouse, drawing attention to the ever present narcotics trade, these areas are notorious for. There is never a signature, never an artist identification, claiming ownership of the work.

Why would anyone do this?

Art As A Public Service

According to Prageeth Ratnayake, artist, exhibitor and the art director at the Sri Lanka Rupavahini Corporation, a mural is the physical manifestation of an idea that cannot be sold, it does not have a price tag or an owner, once the artist has completed it, once the wet paint dries on the wall, it becomes a public property.

“As an artist I sell my work. People come and buy them and hang it on their homes as decoration. But when I draw on a random wall of a random street, that cannot have any capital equity. Your piece can be worth millions but at the end of the day, you are satisfied with giving back to the society,” he noted.

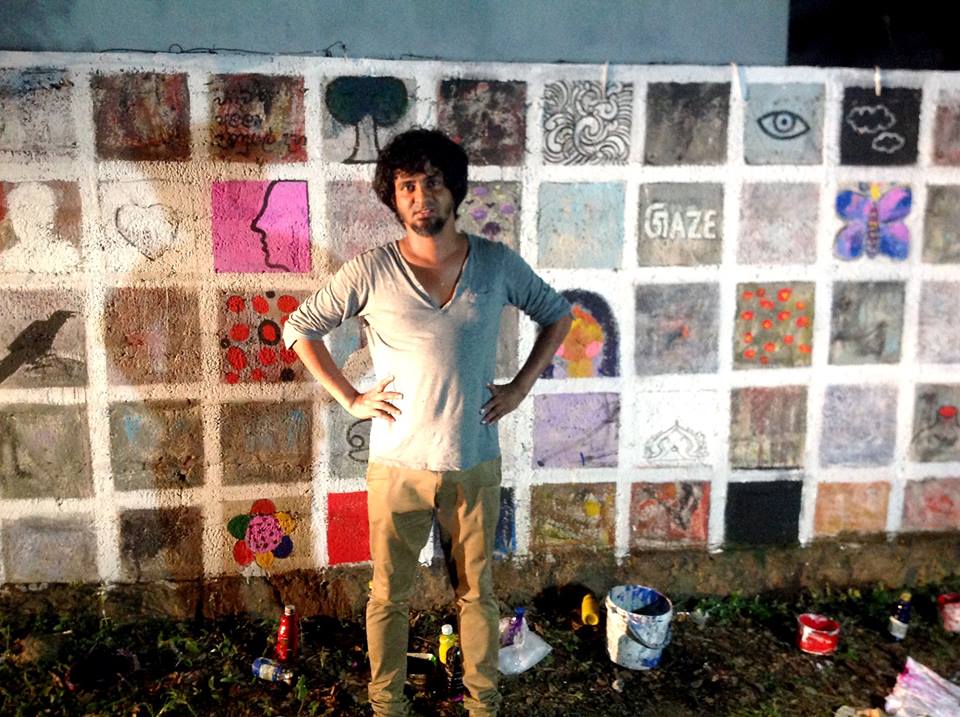

Ratnayake, during his career as a professional artist that spans at least 20 years, did his first mural last February. His piece decorated the road to Bakeriye Kattiya Space in Pannipitiya, which held the Down Town Pulse—a cultural celebration of the new arts.

Ratnayake’s mural took less than two weeks; the selected wall—with permission from the owners—was whitewashed with two coats of paint. His wife and children, together with him, painted the collage of squares, depicting a miniscule portraits, words, a map of Sri Lanka and even a barcode.

Photo credits: Prageeth Ratnayake

“I had the idea in my head. I knew what I wanted the final outcome to look like. This is engagement. My work engages with the society. It takes the discourse out of the heart of Colombo and into the heart of the suburban locales. Once it was done, the nearby residents had a lot of questions. They were intrigued as to what they were; they slowed down when walking past it and I knew people were wondering and trying to interpret it. I didn’t offer any answers and to be honest, the meaning of the mural can be whatever they want. The public engagement that I witnessed after the paint dried down and settled, that feeling of satisfaction cannot be put to words.”

Art As An Identity

Firi Rahman, Parilojithan Ramanathan and Vicky Shahjahan are the most unusual trio you would find in the tapering tunnels of Wekanda and Kompannavidiya, Colombo. They are artists– their lifestyles intertwined with the community they have known since birth; their home and heart, they would say.

For their crusade, murals and street art are a modus operandi through which they are trying to outlast a community that has been degraded and demeaned. Kompannavidiya is known as Slave Island, given its historic context. It has been called a mudukkuwa — a slum, filled with criminals, drug dealers and danger all around.

Photo credits: We Are From Here , Facebook page

The We Are From Here project, spearheaded by Rahman, is an art project to portray that the community is not bound by the stereotypes set by society. The idea is to curate, in a sense, a disappearing community in the face of rapid urban restructuring while portraying a dimension that is not visited, unrecognised, undiscussed and unacknowledged.

“Our intention is to celebrate our neighbourhood. We want to talk about the good things that happen in it and the best way to talk about it is through the people in the community. We want to take the attention away from the negative perceptions with regards to our neighbourhood is viewed through. So since 2015, we have started collecting stories for the project to curate our history in the form of anecdotes and identities,” Rahman said.

Photo credits: Ranmini Gunasekara

For the project, Rahman drew pastel coloured portraits of several individuals from their neighbourhood. One could be seen near a random manioc vendor, another next to a makeshift garage, another alongside a black and white mural of a camera staring back at you.

The locations mattered. The primarily orange, yellow and blue mural next to the vendor told the vendor’s story; he would meet you with a bright smile that resonated through his eyes, tell you his story and if he liked you, he would give you a kadala packet to go. The other of an individual known as ‘Captain’–mechanic, resident of the torn down Java Lane and overall expert in classic motorcycle. The one next to the camera mural was of the artist herself—Rahman drew Shahjahan without her knowledge. Once completed and seen, she said it was the greatest gift one could have given her.

At the moment, there are ten portraits strewn across the many walls of Kompannavidiya. According to Rahman, they have no intention of stopping at ten.

To Shahjahan, the project is all about meeting new people and getting to know them. As an androgynous artist, who went through many a challenges put forward by her own community when she was coming out, she claims to have first hand experience in the stigma that surrounds Slave Island.

“We want to break that stigma. We are getting to know people we didn’t even know lived here. People here have achieved so many things. We have a champion martial artist. We have people who sell food at Galle Face. We have artists like Firi [Rahman] and so many other people, with so much talent. They deserve recognition, they deserve to be identified.”

.jpg?w=600)