On July 8, in the most recent instance of a growing number of drug hauls, the police confiscated a cache of heroin worth over 1.2 billion rupees during a raid conducted in Kalubowila and Battaramulla. This is reportedly the largest stock of heroin seized by the authorities on Sri Lankan soil. Earlier this year, in April, the Sri Lanka Navy and the Police Narcotics Bureau seized over 100 kg of heroin aboard a vessel off the southern coast that was bound for Sri Lanka. These recent hauls come in the wake of several high-value drug seizures over the last few years.

According to Dr. Shanaka Jayasekara, Programme Coordinator for the Indian Ocean Region of the Global Maritime Crime Programme and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), who delivered a lecture on the subject at the Bandaranaike Center for International Studies in late July, these incidents point to a worrying new reality: Sri Lanka is being used as a regional drug distribution hub in the South Asian region.

Where Does Heroin Come From?

There are two major opium and heroin production zones. One is the Golden Crescent, a region that overlaps Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan, with their mountainous peripheries defining the crescent. Afghanistan is the focal point of this crescent, having long been a hub for poppy production. The country currently produces around 80% of the global supply of heroin. The Golden Triangle consisting of Thailand, Laos, and Myanmar meets most of the remaining demand, but mainly supplies South East Asia.

Afghan heroin is grown with Taliban protection in the Helmand province. According to the Afghanistan Opium Survey published by the UNODC, opium cultivation in Afghanistan has hit record high levels with an estimated 328,000 hectares used for poppy cultivation. That’s a 63% increase compared with the 201,000 hectares in 2016. With more opium— and heroin—available, traffickers are looking for new consumer markets.

The Routes

There are three routes for heroin to leave Afghanistan:

The Northern route goes through Uzbekistan and the Russian Federation and ends in Europe. The Balkan route takes it through Iran and Turkey to the Balkan states and then to Europe.

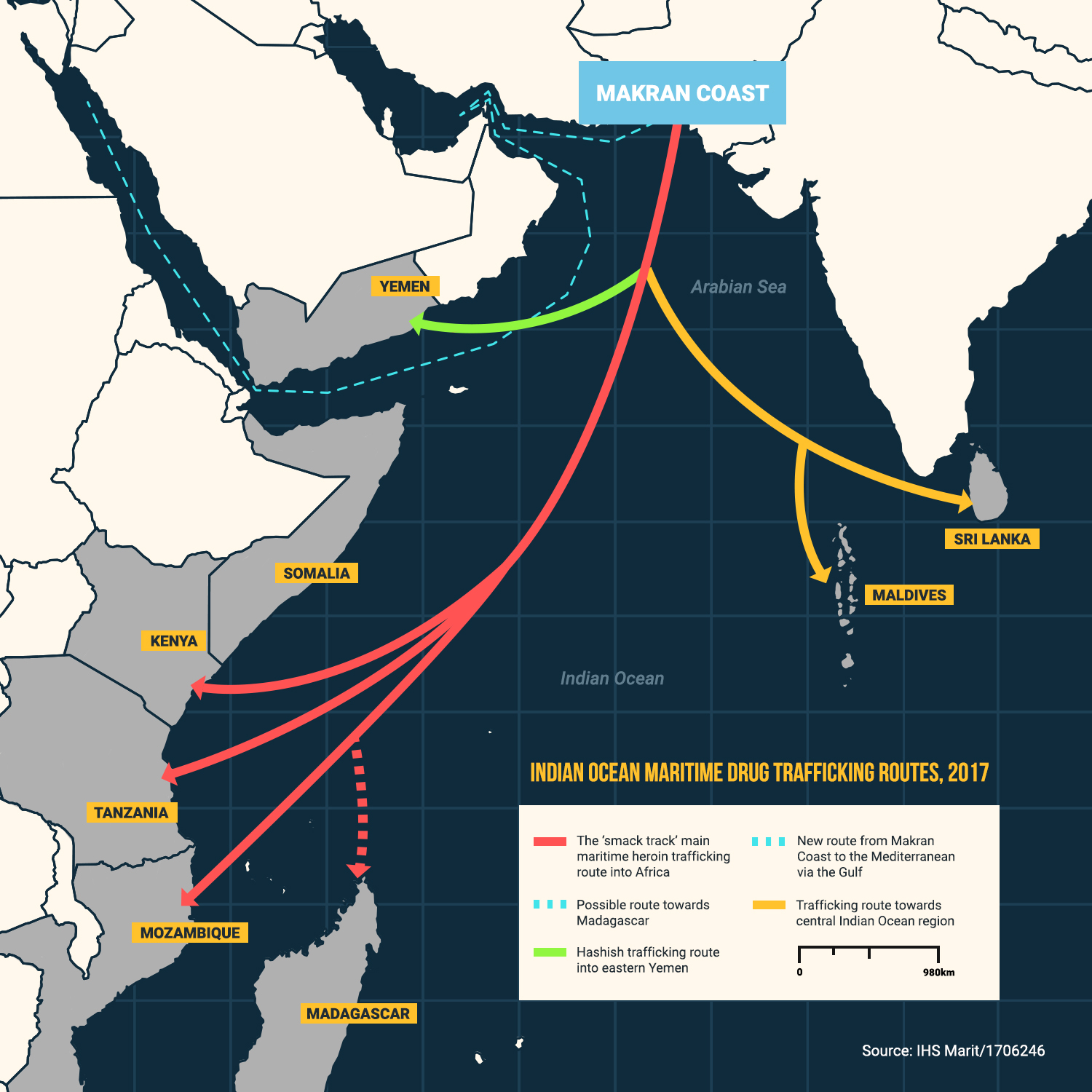

The Southern route is what concerns the nations around the Indian Ocean. On this route, both land and sea transport are used. The advantage for drug smugglers in using a sea route is the lack of jurisdiction on the sea. Any arrests can only be made in a nation’s territorial waters, which only extends for 12 nautical miles from the low-water mark of that nation.

This makes the unmonitored high seas a sanctuary for criminal activity. For any law enforcement vessel to raid a vessel in the open sea, it requires flag state consent or consent from the nation that the target vessel is registered in. This is a process that takes far too long for any arrests to be plausibly made. Often, suspects simply dump the drugs overboard when they encounter law enforcement craft, to eliminate evidence.

Afghan heroin is first taken to the coast of Pakistan by facilitators who connect with the networks that traffic heroin. They take the drugs to the Makran coast of Balochistan, a sparsely controlled, semi-desert coastal strip across Pakistan and Iran, along the coast of the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. From the Makran coast, they are taken by speedboats to dhows, or ocean-going trading vessels that date back to 600 BC. There are hundreds of thousands of dhows in the Indian Ocean in legitimate businesses like cargo transport. Dhows are the predominant form of drug trafficking in the Indian Ocean. They take cargo from the Makran Coast to locations on the East African coast, such as Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, and Madagascar.

In recent times, it appears that a secondary route has emerged, with dhows heading towards Sri Lanka and the Maldives as well after leaving the Makran coast. According to a report on global security and stability issues by the international security and intelligence journal, Jane’s Intelligence Review, this trend was highlighted when almost 200 kg of Afghan heroin, smuggled via a maritime route and transferred to a Sri Lankan fishing boat, was seized in Muthupanthiya in May 2017.

While there is some local consumption of heroin, the larger consignments are likely to be transshipped. The high volumes of the Colombo port make Sri Lanka attractive to drug traffickers who use containers for the entire journey and for onward movement. Dr. Jayasekara says in Jane’s Intelligence Review, “Much of the heroin coming to the East Indian Ocean region is in containerised cargo and trafficked across the world.”

A kilo of pure heroin at around 75% purity is worth around $2,500 when it leaves an Afghan factory after processing. When it gets to the Pakistan coast, its value goes up to $4,000. By the time it’s brought to the East African coast on the dhows at a purity level of 45%, it is worth $12,000. When it reaches Europe, that value further skyrockets to $25,000. Ultimately, what you buy on the street is only at 8-15% purity. With so much room for dilution, the profit volumes and margins in drug trafficking are huge.

Consequences

While the traffic to Sri Lanka and Maldives is relatively new, and not much is known about it, the parallels with the African routes make it important to note what effect the drug trade has had on those nations.

A key example is one of the Southern route’s drop off points: Mombasa, Kenya.

The most obvious risk is that a drug transit hub could eventually create a local user base as well. A 2017 US State Department report confirms this: “Kenya is a significant transit country for a variety of illicit drugs, including heroin and cocaine, with an increasing domestic user population.”

According to Dr. Jayasekara, drug traffickers also took advantage of government corruption in Kenya to funnel large amount of money into the political system, to buy access, influence and protection. It was found that container yards and security for container yards in the Mombasa port were managed by key members of the drug trafficking network. The UNODC suspects that containerisation of drugs takes place in Mombasa and then they are sent to Europe.

Countermeasures

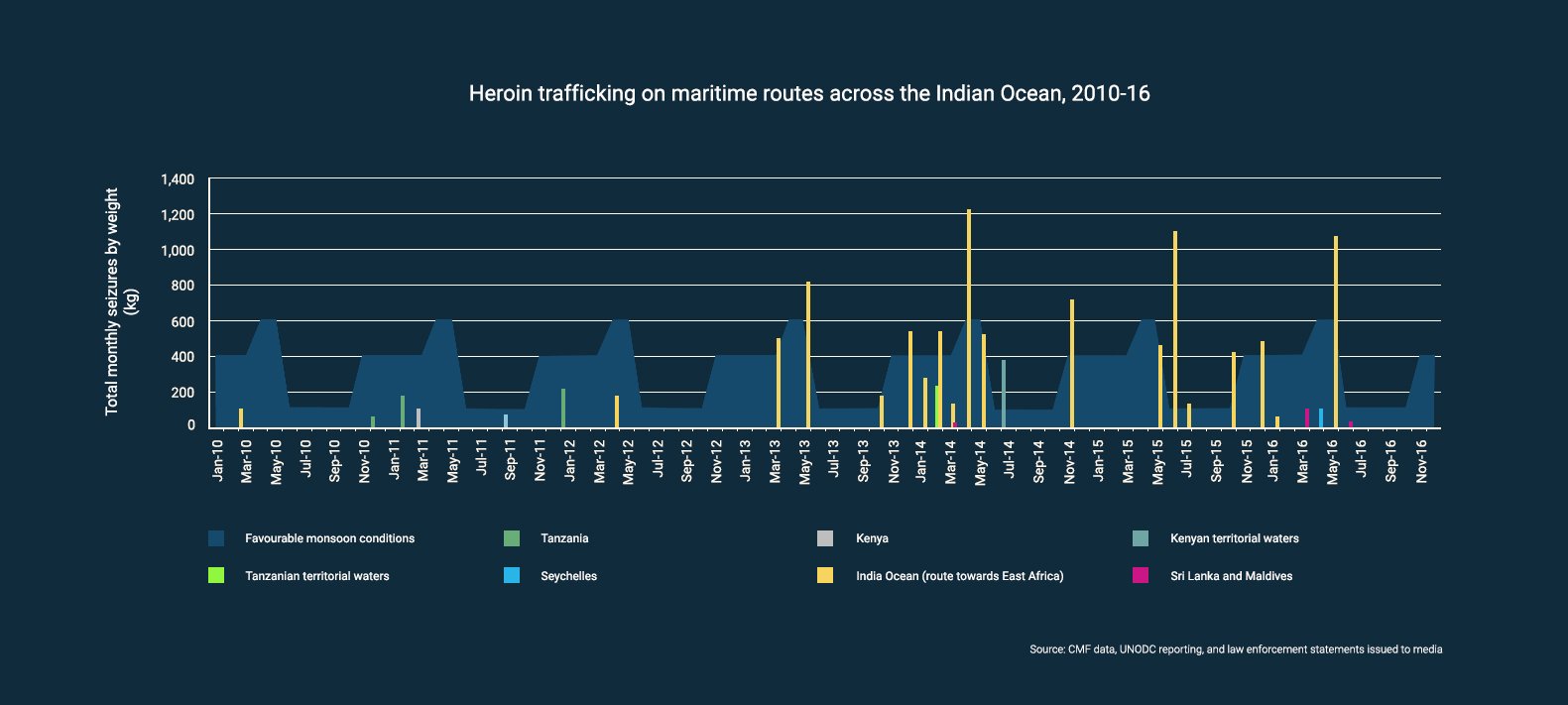

The Combined Maritime Forces is a multinational naval partnership between 33 member nations ranging from the United States to Pakistan. While the combined forces were initially deployed to combat Somali piracy, the partnership has provided the most successful response to drug trafficking vessels of the African coast. However, they are unable to prosecute any smugglers since arrests happen on the high seas. The most they can do is dispose of the drugs and document what they discovered. This is valuable data towards understanding drug trafficking patterns. A Regional Narcotics Interagency Fusion Cell is also part of this effort. Fusion cells collate and share information between law enforcement agencies in order to better combat illegal activity. However, these forces are for the western side of the Indian ocean.

For the Sri Lankan region, two significant initiatives were spearheaded by the Sri Lankan government.

One is the Southern Route Partnership, an umbrella group for national drug enforcement agencies, international organizations and other stakeholders to improve coordination and collaboration on counter narcotics initiatives along the Southern Route. The Southern Route Partnership meets annually. The heads of drug enforcement agencies discuss matters ranging from strategies and maritime drug enforcement dialogues, to training on how to board vessels. In fact, much of the training is done in Trincomalee with the partnership of the Special Boat Squadron training school. They send aid such as interpreters and other necessary resources to help with information gathering, if an arrest is made in a partner nation’s sovereign waters.

The second initiative is the South Asian Regional Intelligence Coordination Centre, a proposed intelligence sharing agency based in Colombo with liaisons from ministries of all member countries. This office’s mission is to work to counter drug- and other transnational crime in the South Asian region.

The Future

Before Sri Lanka becomes established as a drug transit hub, the problem needs be to nipped in the bud. Like in Mombasa, transit points can easily become consumer points as well. Needless to add, if narcotics money enters politics, it would complicate matters significantly. Additionally, if Colombo is labelled as a high risk port, it is likely to affect legitimate trade. Clearing goods coming from Colombo would likely take much longer as they would have to be be scrutinised thoroughly, causing delays to businesses.

It is imperative for authorities to continue to apprehend traffickers and share information with other agencies. Agencies such as the UNODC rely on local authorities to seize and report drug consignments, so that they can use that data to identify routes and patterns. For example, the UNODC collates data on drug stamps. Each drug stash has a stamp, which identifies quality and purity and acts as a brand. If these stamps are found in Europe, they can identify the routes that were used.

Sri Lanka has a pivotal role to play in the Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) of the Indian Ocean. This means that authorities must know what ships are in Sri Lanka’s waters. Current technology is not enough, because MDA requires layers of data from as many sources as possible, such as purchased satellite imagery or synthetic aperture data imagery. Forces like the CMF may not operate on this side of the Indian Ocean, but their surveillance data may be invaluable towards identifying and apprehending ships coming to Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka is located at a strategically important location, thereby welcoming a great deal of maritime traffic. Hence, the country needs to lead the charge in gathering information.

Also, as Dr. Jayasekara stated, the UNODC does not endorse the death penalty for drug trafficking. Western countries often provide information on the condition that prosecution will not lead to the death penalty. By ignoring the moratorium on the death penalty, Sri Lanka risks alienating nations whose help and information we need to combat drug trafficking.

While Sri Lanka is already taking some measures to combat the proliferation of the drug trade, it will become important not just to solidify the progress made, but also use it as a foundation to improve the country’s maritime capabilities.