On the dark, tropical island of ‘O’, humans and spirits live in harmony, and Queen Devi shares a mystical connection with the magical phoenix ‘Maatha’—from whom the women of the island derive their spirituality and power.

When a Prince hears of the beautiful women of the island and invades, abducting the Queen and her phoenix, the spiritual balance of the island is lost, and chaos descends.

Maya, a young woman from the Queen’s tribe, grows up in hiding, watched over by a priestess, Nambi, who trains her to become a warrior—for Maya must one day find and rescue her Queen and the mystical, magical phoenix ‘Maatha’.

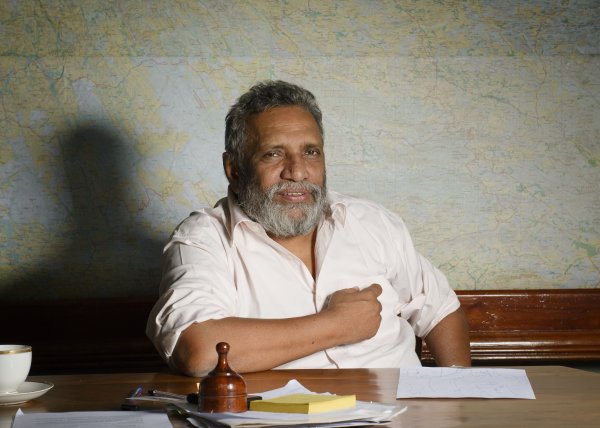

The story is simple, the themes and production, far more complex. Roar Media sat with artistic director Tracy Holsinger to learn more about the mysterious land of ‘O’ and it’s people.

Q: What influenced ‘Maya’?

A: The inspiration for the story of ‘Maya’ comes from two sources. One is the ‘Valahassa Jataka’ (#196, Tale of the Cloud Horse), in which a merchant prince named ‘Simhala’ sails from India to Sri Lanka, where, upon discovering the island is populated by ‘demonic’ women, he gathers an invading force and conquers the island.

Records of this myth can be found in Sri Lanka, India, Nepal and Tibet, but the primary source for this production is the account by the 7th-century Chinese monk and scholar Xuanzang (Hiouen Tsang). Sri Lanka’s origin myth also features a ‘demon’ queen—Kuveni—who is usurped, cast out and killed by her own people. The similarities between the stories prompted me to explore the notion of demonisation and what might cause women to be perceived as such.

In 2016, my husband Deshan Tennekoon conceived an idea for a graphic novel which never came to fruition, but which he has allowed me to explore theatrically. In it, a young warrior named Maya has to rescue a Queen and bring balance back to the land. So I took the ‘Valahassa Jataka’ and the story my husband wrote, and intertwined them.

Q: How, precisely, does ‘Maya’ disrupt patriarchal narratives?

A: The need to address the imbalance in the many tales that depict women as demons or unwholesome or subservient has always been on my mind. It is steeped in our culture, mistaken as tradition and perpetuated by men and women, Maya is inspired by exceptional women in Lankan mythology, like Kuveni, Queen Viharamaha Devi and Queen Sugala.

Q: How have you used different theatre forms and techniques to tell your story?

A: Since 2011, I have often toyed with the idea of making a non-verbal play in order to overcome language barriers while touring the island. The concept was to create a physical theatre production that would draw on traditional Lankan practices. [But] as the play developed, we found it impossible to tell this adventure without language, and so dialogue is used sparingly and tri-lingually.

Everything is very physical. There is a lot of mime, and we’re using a lot of masks – all very much influenced by traditional Sri Lankan theatre forms, including the circular shape of the stage. We’ve even incorporated Angampora – Sri Lanka’s traditional form of martial arts.

We’re also using a little bit of kung-fu, influenced by Asian art forms which are both different and similar – our cultures have histories of non-verbal theatre, movement, and the use of traditional masks, so I really wanted to explore all those elements with this play.

Q: You have employed devised theatre. Does devised theatre and the near absence of dialogue challenge the actors as much as the viewer?

A: It’s been difficult. We are all actors (we have two professionally trained dancers, but the rest of us are theatre people) and we know physical theatre, but trying to communicate without language is still difficult. There are moments when it is too tough, and that’s where you come across the language—when we really couldn’t figure out how to put what we were trying to say across!

Also, I love language and I come from a very language-rich background, so I didn’t really want to get rid of language altogether, either. So it’s kind of a hybrid. I’ve never done anything like this before, and neither has the cast.

We’ve been rehearsing since June, and it’s really been quite a process. How do you distill one sentence into one movement? It’s been a lot of exploring, trying to figure things out and failing—but that’s part of the fun, really.

Q: Why did you decide to make the play trilingual?

A: In our work as a theatre company (we’ve been making original work since 2009— our first original play was The Travelling Circus) we have been really engaged with community-building in the aftermath of war. All our plays since 2009 have been original and have been based on trying to create more understanding between communities, and exploring what has happened to us in the last 10 years.

In 2016, I did my first Sinhala play – ‘Karakena Keliya’, which was the Sinhalese version of The Travelling Circus. I created that play together with the Janakaraliya Cultural Foundation, whose work is incredible. They’re a multilingual theatre group, that travels around the island performing plays in Sinhala and Tamil and it was amazing to be able to make my first Sinhala play with them.

Since then, we’ve been doing a lot more work out of Colombo. We’ve been working with students around the country in the North, East and South—just trying to engage with the reconciliation process. So for me, this was just a natural progression of the work we’re doing. Just to reach out, reach out and reach out, all the time! Make new friends, make the plays and make more connections. That’s the idea.

‘Maya’ goes on board at the Lionel Wendt Theatre from September 6-8.