Sometime between November 9 and December 9 this year, Sri Lanka will hold its eighth presidential election to decide who will lead the country for the next five years. As with any election, the period leading to the election will be filled with fervid political activity as parties decide on which candidate is best able to amass the votes necessary to win.

For many, this election, like others before, will be nothing more than a cacophony of political noise and enthusiastic ululations. But because the active participation of citizens in politics and civic life is key to a functioning democracy, a primer is timely. Find out what the Presidency is, why the position was created, and what powers and limitations come with it.

The Presidency

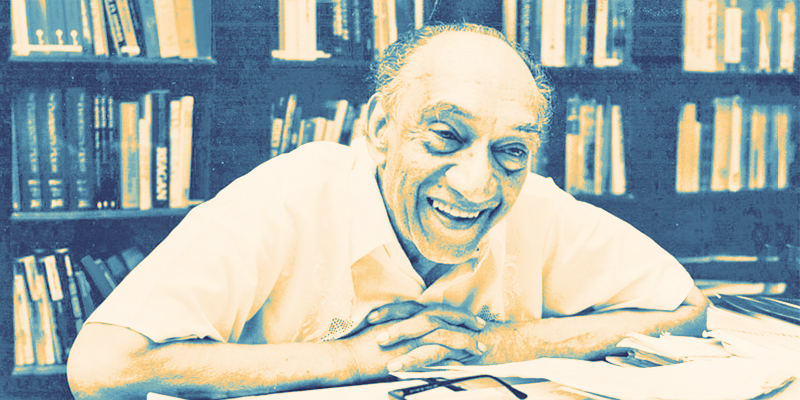

The Presidency was introduced to Sri Lanka through the First Republican Constitution (1972), though at that stage it was a nominal, de jure office—power actually lay with the Prime Minister (Sirimavo Bandaranaike) in a parliamentary system of government.

This changed with the Second Republican Constitution (1978), which introduced a presidential system of government and an Executive Presidency that gave the President (J. R. Jayawardene), sweeping powers, the extent of which is being questioned, to date.

J. R. Jayawardene had advocated for the Executive Presidency from as far back as 1966, on the grounds that a stable executive could not be easily swayed by internal or external pressures and that it would ensure the protection of minority interests.

This is now disputed, and the Executive Presidency has become a highly contentious issue in contemporary Sri Lankan politics.

The Electoral System

Ceylon held its first national election under the parliamentary system of governance in 1947, but although the Executive Presidency was introduced in 1978, it wasn’t until 1982, when J. R. Jayawardena was seeking a second term in office, that the first Presidential election was held.

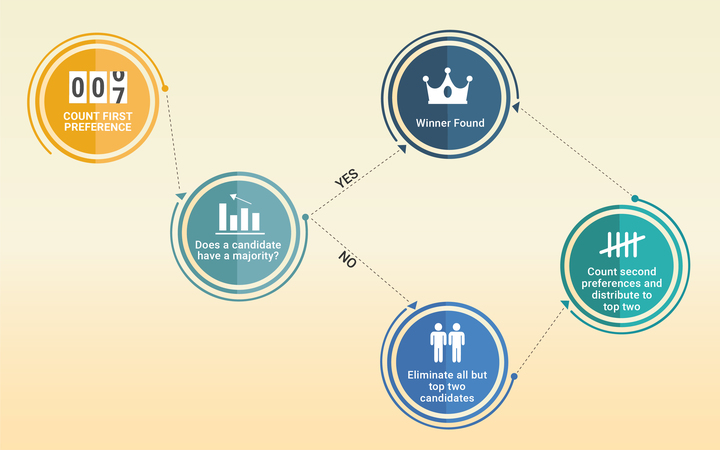

The election is held islandwide on one day, and the President is elected using a variation of the ‘ranked-choice voting’ (RCV) or ‘contingent vote’ system, in which voters rank candidates in order of preference (limited to three preferences).

How Often Is It Held?

The First Republican Constitution (1972) set a limit of four years and two terms on the Presidency, but the Second Republican Constitution (1978) extended it to six years, with a two-term limit.

In 2010, the 18th Amendment to the Constitution removed that two-term limit, creating the conditions for authoritarianism, but the 19th Amendment to the Constitution, passed in 2015, restored it, shortening, as it did, the length of a single term to five years.

How Is It Held?

A Presidential election must take place not less than one month before the expiration of the term of the President, but not more than two months before. However, the President is allowed to appeal for a second term any point after four years of his first term has been completed.

As a President’s official term begins to draw to an end (or if the President expresses an interest in calling an election early) the Elections Commission must publish the nomination order, which is essentially a Gazette that sets a date for the acceptance of nominations, not less than 16 days and not more than 21 days after. Nominations are accepted on that single day, typically between 8 AM and 11 AM (with an additional period for objections), and a date for the election is fixed not less than four weeks and not more than six weeks from the day of nomination.

Thereafter a minimum of one month and a maximum of six weeks are allowed for election campaign work—but all election campaign work must end 48 hours prior to the election.

A host of rules govern the selection of candidates, and specific rules are in place to ensure the ballot is cast in a free, fair and secret manner—aspects we’ll explore in greater detail during this series.

Voting typically begins at around 7 AM and ends at 4 PM. At 4 PM, postal votes—which allow those unable to appear at their polling stations to vote early—will be counted. These include state officers engaged in election duties, public servants engaged in essential services and personnel of the tri- forces, the police and Civil Defense Force who would be engaged in duty all over the island.

Meanwhile, the counting of ballots cast at polling stations will begin at around 7 PM, after ballot boxes have been safely transported from polling divisions to a counting centre.

Five counting agents from each contesting political party or group can be appointed to a counting centre and two agents from each contesting political party or group can be appointed to a postal vote counting centre to ensure the counting is being conducted in an unbiased manner. In addition, independent observers and organisations are entrusted with ensuring the impartiality of the election.

A counting centre is typically allocated to about 10, 000 registered electors, and the head of the counting hall, a senior public servant known as the Chief Counting Officer, is appointed to preside over the counting, aided by six Assistant Returning Officers and between 20-30 government servants serving in varying capacities.

In the ‘ranked-choice voting’ (RCV) or ‘contingent vote’ system, in which voters rank up to three candidates based on preference, if no candidate receives a majority (more than 50%) of votes, then all but the two leading candidates are eliminated and second preferences (if it is for one of the two remaining candidates) are counted towards their previously received votes. The candidate with the most amount of votes collectively accumulated in this manner is declared the President.

What Duties Must The President Perform?

Foremost among the duties of the President is the responsibility to ensure that the Supreme law of the land, the Constitution, is respected and upheld. The President must also promote national reconciliation and integration—this means ensuring the various religious communities, ethnic communities and other identity groups are protected and have equal rights and opportunities before the law.

It is also incumbent on the President to ensure that the Constitutional Council—that was reintroduced in 2015 after being removed by the 18th Amendment in 2010—functions as it should, maintaining independent commissions and monitoring its affairs so as to depoliticise the public service. The President is also expected to ensure free and fair elections in the country.

What Powers Does The President Have?

As Head of State, Head of the Executive, Head of the Government, and the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, the President has a wide range of powers. This includes the power to declare war and peace and to declare a state of emergency (although parliamentary approval is needed to prolong a state of emergency for more than a month).

With regards to the legislature, the President is empowered to make the Statement of Government Policy in Parliament, which is essentially the declaration of a government’s political activities, plans and intentions for the entire legislative session. In addition, the President has the power to summon, prorogue or dissolve Parliament.

The president is also the custodian of the ‘Public Seal of the Republic’, or the official seal of Sri Lanka, giving him the authority to authorise the appointment of, among others, the Prime Minister and the judges of the Supreme and Appeals Courts and President’s Counsels. The President will also appoint, accredit and receive ambassadors, high commissioners and other diplomatic agents.

How Are The President’s Powers Curtailed?

The restraints on the President are complex, open to interpretation by experts, but limits have been placed on the most powerful office in the country. For instance, while the President is immune to civil and criminal action for as long as he holds office, he also has to ensure his actions are “not inconsistent with the provisions of the Constitution or written law, as by international law, custom or usage, that the President is authorised or required to do.”

The Parliament can also hold the President responsible for the due exercise, performance and discharge of his powers, duties and functions under the Constitution and any written law. Any Member of Parliament who feels the President is guilty of intentionally violating the Constitution, or is guilty of treason, bribery, misconduct, corruption or abuse of power, or feels that the President is incapable of discharging the functions of his office due to mental or physical infirmity can have the President investigated by the Supreme Court and removed by a vote in Parliament.

This is not easily done, however. An impeachment motion, as it is called, must be endorsed by no less than two-thirds of the Members of Parliament and the President is allowed to defend himself before the Supreme Court—either in person or by an attorney-at-law—before it makes a determination on the charges. If the Supreme Court rules in support of the charges, the Parliament must vote once again with a two-thirds majority to remove the President.

Similarly, the 19th Amendment to the Constitution placed several checks and balances on the President’s powers. For instance, it reintroduced the Constitutional Council (brought in with the 17th Amendment in 2001 but taken out with the 18th Amendment in 2010) that is tasked with maintaining independent commissions.

While the President is allowed to recommend Chairmen and members to the various Commissions (Elections Commission, National Police Commission, Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery or Corruption…) those recommended cannot be appointed without the approval of the Constitutional Council—which includes the Prime Minister, the Speaker and the Leader of the Opposition—effectively curbing some of the powers of the Executive Presidency and strengthening other institutions of governance.

With election season upon us and the highest office in the country open to a number of aspirants, it is a good time as any to learn about the history, systems and powers enshrined in this office, and to be able to make an informed decision at the election. What do you think about the Presidency? How do you feel about the Executive Presidency? Should Sri Lanka’s President be immune to internal and external pressures? Does the Executive Presidency really protect minority interests? Should the Executive Presidency be abolished, as some think it should be? These are the points to ponder before an election.