“Guné Aiya, mata parippu kilo ekak denna.” (Guné, brother, give me a kilo of dhal)

M. Gunasiri (50) or Guné Aiya as he is known, dutifully weighs a kilo of dhal, bags it, and hands it over to the customer, a frail man from the neighbourhood who plucks coconuts for a living, who in turn hands over a crumpled hundred rupee note, collects his change and sets out in the direction of his home.

But as Gunasiri attends to his next customer, a thought weighs heavy on his mind— he has just made a loss of Rs. 60 on that sale. And by the time he exhausts his stock of dhal alone, he would have made a loss of a few thousand rupees. A princely sum, considering the circumstances.

Gunasiri is the owner of a small kade (shop) by the beach between Dehiwala and Mount Lavinia, and keeps area residents supplied with their daily essentials. His customers are loyal, and frequent his shop often, especially considering the fact that the town is nearly a kilometre away by road.

But with the government announcing a slew of relief measures as a result of the novel coronavirus COVID-19 that has brought the economy to a grinding halt, small, independent retailers like Gunasiri are hit hard.

Canned Fish And Dhal

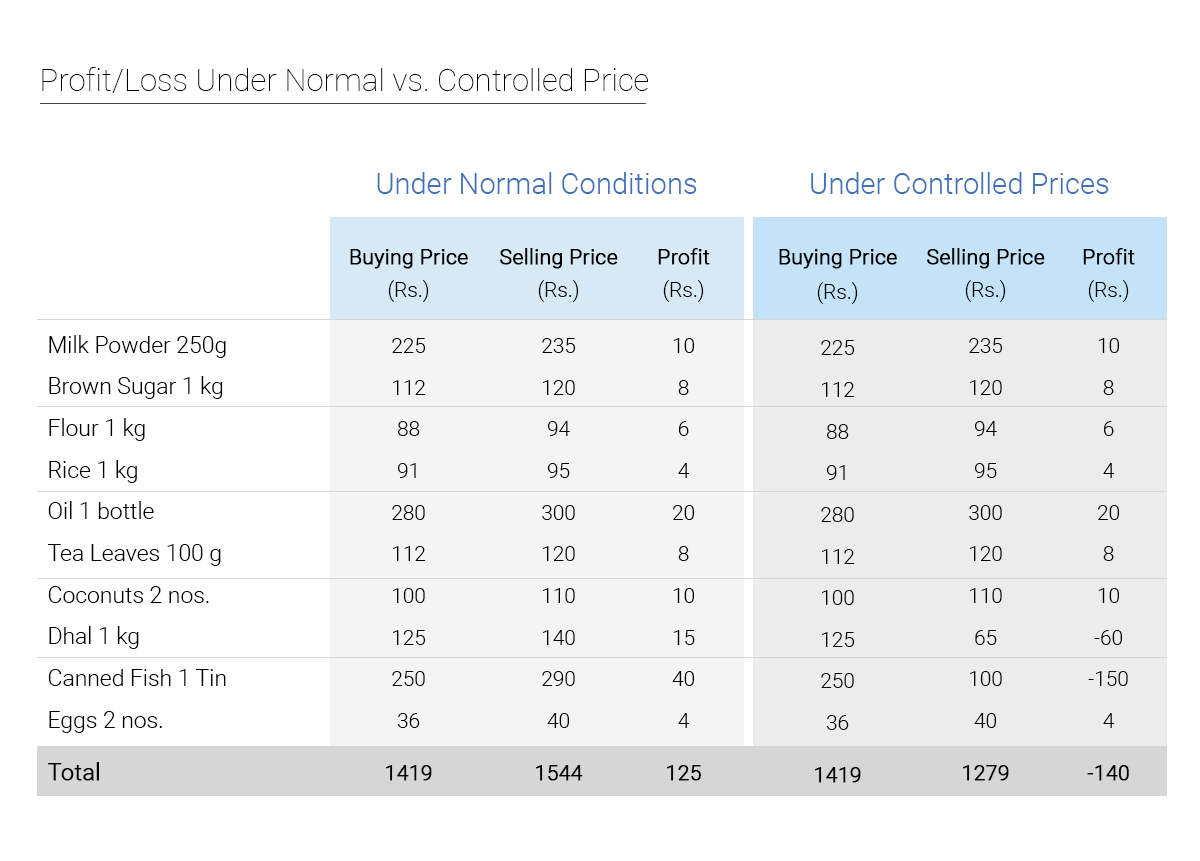

As part of the relief package, maximum retail prices were imposed on a few essential items— Rs. 100 for a tin of canned fish, which is otherwise priced at Rs. 290 and Rs. 65 for a kilo of dhal, which otherwise retails at Rs. 140.

“It’s a good decision, no two words about that. But I wish they had come up with some mechanism to compensate small business owners like me too,” Gunasiri told Roar Media. “See, they have imposed a curfew now. I also need cash to survive, I can’t afford to keep on losing money like this, mahattaya,” he continued.

His concerns are valid. As at the time of writing, the government has not made clear if any mechanism will be put in place to compensate independent retailers for the loss they will incur as a result of imposing price controls overnight, although they have said they would compensate importers of dhal and canned fish.

Canned fish and dhal may be just two of a host of items sold at small shops like Gunasiri’s, but slim margins in the retail industry make it near impossible to make up for losses with the sale of other items. “Our shop is a medium scale one. If a customer purchases goods for Rs. 1,000, we would have a profit of around Rs. 75 at best,” Jameema Raffaideen (20), told Roar Media.

Raffaideen and her family live in a shophouse in Ampitiya, Kandy. The income from the store goes largely towards domestic expenses and to educate Raffaideen’s two younger siblings. The store is restocked every two weeks, and at the time of the government’s announcement, had 100 kilogrammes of dhal and 25 boxes of canned fish (each containing 24 cans), all purchased at the previously prevailing wholesale prices.

“On the one hand, we have to take on a huge loss. But on the other hand, we can’t say no to our customers. Some of them are daily wage earners and the price reduction is a big relief to them in times like these,” Raffaideen explained of her predicament.

“It is commendable that the government has taken steps towards easing the burden on the poor, especially during a time like this. But, controlled prices can also lead to shortages, as producers lose incentive and ability to stock these products. In addition, when imposed with no prior warning, price controls force smaller businesses to take losses, which can sometimes be inequitable. Despite the good intentions behind this decision, it has the potential to make the situation worse,” Aneetha Warusawitarana, Research Manager, Advocata Institute told Roar Media.

But, is there a better way for the government to deliver relief to the poor in times like these, without hurting intermediary retailers?

This is a tough question to answer, and governments around the world in similar predicaments are each pursuing unique policy solutions. The UK, for instance, unveiled a relief package that promised wage subsidies for staff on payroll and is promising similar relief measures for those self-employed. India announced a USD 22.5 billion economic stimulus package that includes direct cash transfers and free packs of essentials to protect daily wagers, small business owners, and low-income households.

Multilateral agencies, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), have also recommended cash transfers, wage subsidies, and tax relief as its preferred immediate policy measures—all of which will empower the end consumer. But there has been no communication from the government in this regard—thus far.

At the small kade between Dehiwala and Mount Lavinia, Gunasiri’s battery-powered radio crackled to life as a newsreader announced the reimposition of curfew in Colombo. “Ah mahattaya, can you hear this? They are going to re-impose the curfew soon,” Gunasiri said, fiddling with the volume controls. “I have no intention of getting rich while everybody else suffers because of this virus. I also don’t have kids or loans to pay, so maybe I can manage a little bit better compared to others. But, I also can’t keep making losses forever and go out of business as a result. We need to eat, and for that, we need money right?”

Gunasiri’s voice trails off. He can see a group of 4 or 5 women hurriedly making their way towards his shop. Gunasiri knows them well and knows what they will buy. He readies his scale and waits. Who knows, perhaps these last few sales will tide him over till the curfew is lifted.