Just last month, Sri Lanka, Japan and India signed a Memorandum of Cooperation (MoC) on the development of the East Container Terminal (ECT) of the Colombo Port. However, trade unions were quick to express fears that the terms of the deal would be disadvantageous to the country.

The unions even threatened to shut down port operations during the early stages of the negotiations, their primary grievance being that Sri Lanka would be handing over key port facilities to foreign nations.

After China was given a controlling equity stake and a 99-year lease of the Hambantota port, there is a suspicion that this deal is also a result of escalating geopolitical competition between regional powers.

But when the matter was brought up in Parliament by JVP leader Anura Kumara Dissanayake, Minister of Ports and Shipping, Sagala Ratnayaka assured the House that the ECT would not be sold to any foreign country.

Why Does Sri Lanka Need A Bigger Port?

The urgency of expanding the Colombo Port comes with changes in the global shipping industry. The size of cargo ships is limited by whether they fit through the locks of the Panama Canal. These ‘Panamax’ ships, that fit through the original canal, are able to dock at Colombo Port. But after the construction of an expanded series of canals in 2016, a new class of larger ‘Post-Panamax’ ships was created, which require deeper harbours and larger cranes to dock.

The ECT project involves dredging the seafloor to accommodate the increasingly common Post-Panamax vessels, and possibly even ‘Super Post-Panamax’ vessels that cannot even fit in the new locks. But the trade unions still worry that the revenue from this shipping will go to the foreign investors and not to Sri Lanka.

The Terms Of The Deal

In 2017, the Colombo Port handled as much as 6, 209, 000 TEU (1 twenty-foot equivalent unit = 1 container box) of cargo. Located along a vital international trade route, Colombo has the 24th busiest container port in the world, with five terminals currently operational.

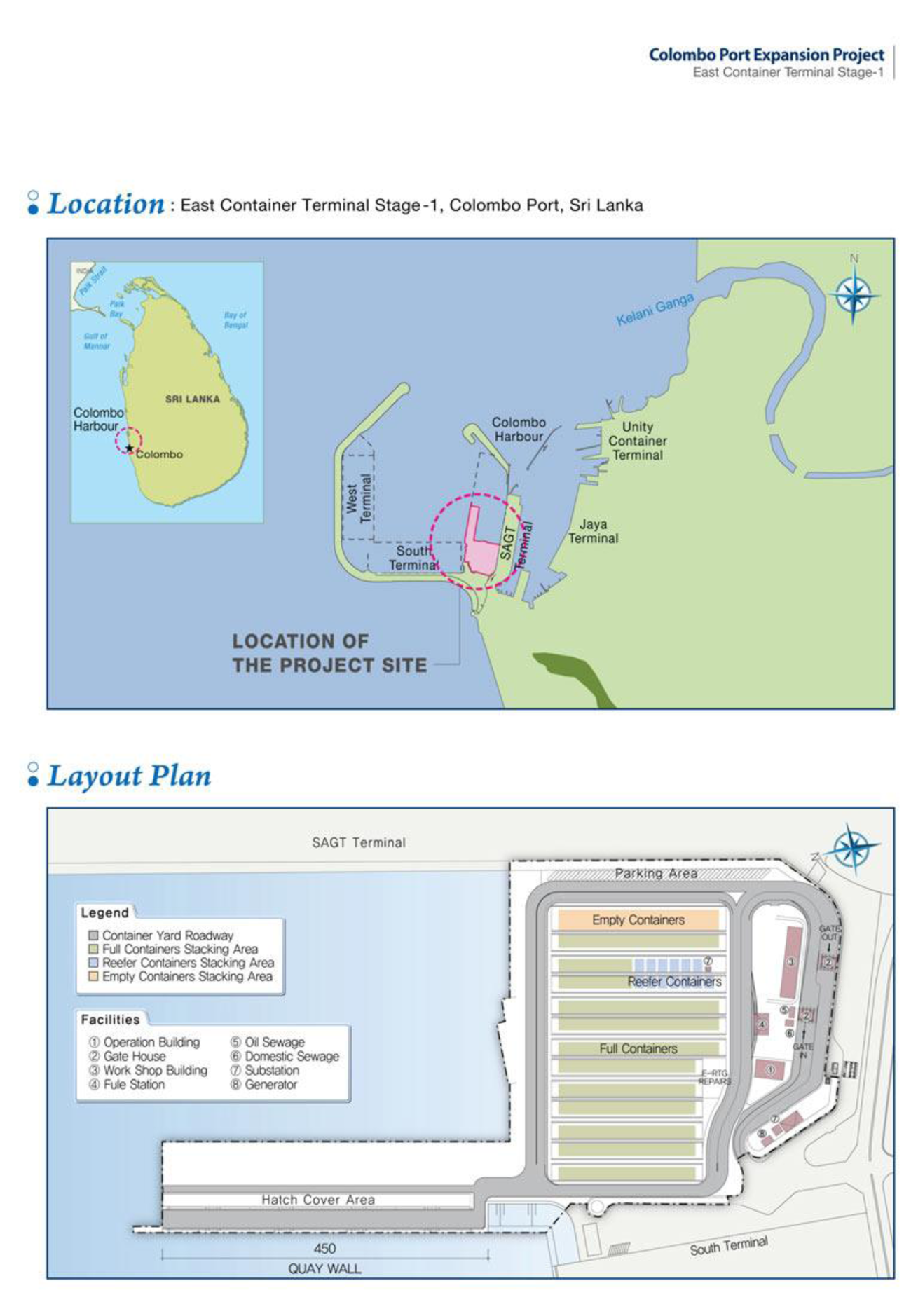

These four, which are part of the old port, are the Jaya Container Terminal, the South Asia Gateway Terminal, the Unity Container Terminal, and the Colombo International Container Terminal. The Colombo Port Expansion Project aims to develop three new terminals, using land reclaimed from the ocean. Construction of the Colombo South Terminal was completed in 2013, and it is now operational, and the construction of the ECT is set to commence this year.

Minister Ratnayaka explained that the Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA) has only had funds to develop the first stage of the ECT. But according to the National Port Masterplan, both the first and second stages of the port have to be developed at the same time to improve the capacity of the terminal, he told Roar Media. It is for this reason that the SLPA decided to develop both stages with a concessionary loan of 500-800 Million USD for 40 years at 0.1% interest from Japan, as a joint venture together with India and Sri Lanka. “Under the agreement, the SLPA will continue to hold the 100% ownership of the terminal and will retain 51% of the Terminal Operator Company (TOC) that will be formed to handle the operations of the terminal, with a 49% stake for joint venture partners.” Ratnayaka told Roar Media, “Therefore, the SLPA will not lose the controlling power over the ECT.”

Japan has provided cooperation for the development of the Jaya Container Terminal since the 1980s, and around 70 % of Colombo Port’s transhipment business is from India. It was therefore reasoned by the SLPA, that Japan and India would be beneficial partners to develop the ECT.

But trade unions affiliated to the Ports Authority threatened to cripple operations at the Colombo Port if the Government failed to cancel the joint MOU on the ECT with Japan and India. Their fears are heightened as the deal comes at a time when China is using the Belt and Road project to increase its influence in the region, and Japan also aspiring to play a significant role in the area by pushing its Free and Open Pacific Ocean and Indian Ocean strategy.

The trade unions point out that the long-term profitability of the Colombo Port will be affected by handing over the only deep-water terminals in Sri Lanka to two foreign countries. “During the past 40 years, the governments that were in power have taken steps to privatise ports, terminals, and these actions have not yielded any positive results,” said Chandrasiri Mahagamage, General Secretary of The All Ceylon Port General Workers’ Union. “Even though we have 51% shares, the operations will be handled by Japan and India, which means the recruitment would also be done by them and not Sri Lanka.”

Is This The Best Way To Develop The Port?

Aneetha Warusavitarana, a research analyst at the Advocata Institute, believes that there is a conflict of interest because of the government’s position. “The government should most definitely not be both a player and a regulator, but right now, the government plays both roles,” she said. Parliamentarian Anura Dissanayake echoed these statements when the issue was brought up in Parliament, stating that “governments are only caretakers, rather than owners of national assets, and as such cannot divest them.”

Seaports are interfaces between several modes of transport — they are multi-functional markets and industrial areas where goods are not only in transit, but they are also sorted, manufactured and distributed. Therefore, they must be integrated within logistic chains to properly fulfil their functions. Additionally, there are ‘ancillary services’ a port requires, such as logistics, bunkering, marine lubricants, freshwater supply, offshore supplies and ship handling, warehousing and many more. Warusavitarana believes that, “if a profitable and productive terminal creates a well-functioning port, allowing ancillary services to grow, then we should be looking to the private sector for investment and not the government.”

When comparing the success of the different terminals, Warusavitarana has found that the privately-operated terminals greatly outperform the government-operated Jaya Terminal. “The performance of the Jaya Container Terminal, in comparison to the private terminals, makes it clear that the government is not as effective as the private sector. It should limit itself to the task of regulation,” she said.

“Of course, when advocating for government regulation, one wants to steer clear of the miles of red tape that the government is fond of,” said Warusavitarana. “A caveat of this argument is that a balance is struck, so that regulation does not stifle innovation or investment,” she said, adding that the role of the government should lie solely in being a regulator. If the Colombo Port is to grow while remaining efficient and profitable, regulation is required to address anti-competitive practices, monitor performance, and enforce standards.