Three-and-a-half billion years ago, our planet was in the midst of a decisive transformation. Until then, meteorites had rained down onto a molten landscape and boiled the oceans, making the six-hour days blisteringly hot. Smokey by-products of the volcanic landscape choked the air, making it heavy, acrid, and unbreathable. The sun was dimmer but the world was warmer; all this extra heat came from below, as the planet’s core cooled off through volcanic vents. The moon had just formed following a forgotten planet’s violent impact with the Earth and was much closer to us then, its pockmarked face mirroring our crater-ridden crust, and filling the night sky. Lava flowed freely, smoke billowed, and oceans roared, but little moved of its own accord—until somewhere between 3.4 and 3.8 billion years ago.

According to Dr. Cyril Ponnamperuma, a 20th Century Sri Lankan philosopher and chemist, this hellish Earth was the cradle of all civilisation; life spawned, he claimed, from normal atoms and normal molecules interacting through normal chemical reactions. The move from inanimate matter to life is a process neither fully understood nor universally agreed upon, yet Ponnamperuma staunchly claimed that our most ancient of ancestors were nothing more than complex chains of atoms.

Born on October 16, 1923, Ponnamperuma was best known for this stance in the origin of life debate. According to Prof. Saman Seneweera, director of the National Institute of Fundamental Studies (NIFS)—a position Ponnamperuma himself once filled—he cultivated these ideas through his “pioneering work in chemical evolution”, which aims to tell the story of how chemistry became biology—or how the non-living became alive.

A Sri Lankan whose academic endeavours took him around the world: from Chennai to study philosophy to Berkeley to read for a PhD in chemistry, and to NASA as an exobiologist piggybacking on the Apollo and Voyager missions, it was at the University of London’s Birkbeck College that Ponnamperuma started musing over life’s beginnings. His background in the chemical sciences, and his application of its experimental and theoretical methods to tackle the issue of life’s genesis—one of philosophy’s most enduring questions—made him a “world-acclaimed scientist”, according to Nalaka Gunawardene, a Sri Lankan science journalist writing at the time.

His charming and affable personality made him widely accepted in Sri Lanka too. A keen populariser of science and technology, “He was a world-class researcher, as well as a very good administrator of scientific institutions—two talents that are not usually found in one and the same person”, Gunawardene told Roar Media. This ensured he was politically and academically relevant, and that he had a competent voice with which to talk about science policy in the country. With studies looking down to the depths of the ocean and up to the outer reaches of our solar system, Ponnamperuma’s scope was as large as his ambition, paralleled only by his enthusiasm for spreading science in the developing world and at home.

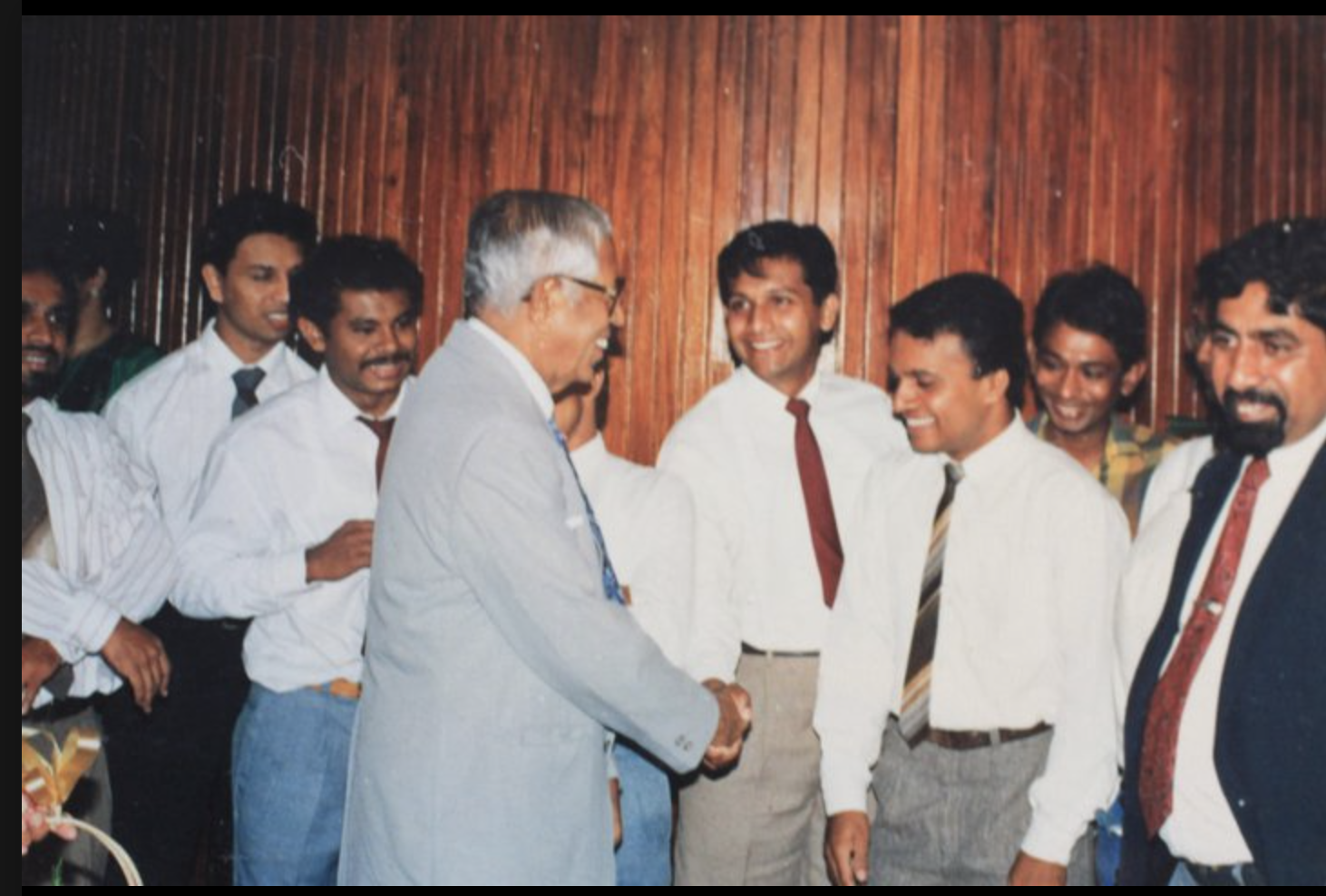

Image courtesy: Prof. Saman Seneweera

Origins Of Life

The idea that the distinction between “life and nonlife [matter] is perhaps an artificial one” is a daring and undoubtedly difficult proposition to prove. Perhaps it was Ponnamperuma’s philosophical inclinations that led him to pursue such a radical stance on the nature of life on our planet. For the rigorously rational, the appeal of such a theory in explaining life’s origins is clear: it requires no divine intervention, and posits the existence of life only where it has been directly observed—on Earth.

Ponnamperuma was a proponent of abiogenesis: the idea that life arose from chemical reactions, whose constituent parts were nothing more than the ordinary matter that we see around us, and the energy driving those processes. Life, he claimed, “is only a special and very complicated form of the motion of matter” (Ponnamperuma, 1964), and likely materialised in ancient clays, in which he claimed “there is probably today more living matter … than above the surface or in the waters” (1964).

Towards the end of his career, Ponnamperuma took to the idea that hydrothermal deep-sea vents may have been the breeding ground for our most ancient of ancestors, an idea that has gained traction in the past two decades, and which is in keen development to this day. The idea is a compelling one: it provides early life with the immense amounts of energy required to sustain itself, and drenches it in water—allowing for the easy transference of energy and matter from the cell to its environment and vice versa.

As editor of the journal Origins of Life, which described itself as a “vehicle for astronomers, geologists, chemists, and biologists to publish their contributions which had a special bearing on the whole question of life’s beginning”, Ponnamperuma facilitated the quest for life’s story through the amalgamation of a variety of disciplines. His personal place in this quest consisted of theorising over the reactions through which inanimate molecules could evolve into living, organic matter.

A background in chemistry was invaluable in this regard: the ability to compose and conduct experiments that directly tried to synthesise the building blocks of life made Ponnamperuma more than just an armchair theorist. According to Seneweera, during his tenure at the Ames Laboratory in Iowa in 1984 Ponnamperuma cooked up five ingredients of RNA and DNA in the lab, as well as the energy-transporting molecule ATP, which was “a huge step for biochemistry”, in demonstrating the emergence of organic matter on Earth of its own accord, and earned him a nomination for the Nobel Prize in chemistry.

For life to stem from those ordinary particles around us presents us with an emphatically humbling view of our place in the cosmos. Just as Darwin’s theory on biological evolution through natural selection whisked away the pedestal humans contrived themselves to be on above all other life, Ponnamperuma’s views on chemical evolution put life on par with everything else in the universe: not only are we star stuff, but the essence of our being and our consciousness is nothing more than it.

Image courtesy: Prof. Saman Seneweera

Science & Sri Lanka

In the 1980s, around a decade before his passing, Ponnamperuma took a keen interest in the role of science in Sri Lanka, and was appointed as then-President J. R. Jayawardene’s personal advisor in the field. He was optimistic about modernising Sri Lanka’s scientific standards and spreading interest for it among the public.

He took over as director of the NIFS (then IFS) in 1984, and worked on incentivising science and increasing the accountability of researchers. “He was the first in Sri Lanka to organise a school science programme”, Seneweera told Roar Media. For many children, this would’ve been their first encounter with science as more than a school subject. “Ponnamperuma would have open days at the NIFS, bringing in bright school kids to meet and talk to researchers and and consider future careers”, Gunawardene said. “Unless kids could see how exciting research work was, they would be pushed into the traditional, typical careers of doctors, engineers, or accountants. He wanted to attract the best talent to science.”

This openness not only helped grow public interest in the sciences, but also allowed researchers to be held financially accountable to the rest of the country. “Since most scientific research and institutions were supported by public funds”, Ponnamperuma told The Scientist in 1987, “the bill-paying public had every right to know what scientists were doing.” To this end “he made the NIFS very accessible to journalists, to school children, and to anyone else interested in what was going on in the institute”, recalled Gunawardene. “This was different from the ivory tower approach adopted by other research institutes at the time.”

The biggest hurdle faced by Sri Lanka’s scientific community at the time was, indeed, this approach of self-interested individualism. “Prof. Ponnamperuma wanted to create a future where we all [could] work together as a team”, said Seneweera, “and he tried to make the NIFS an institution where one could do multidisciplinary science in one place.” But it wasn’t only collaboration between the sciences Ponnamperuma tried to facilitate: he also talked about government ministries working on research and development together, to avoid “splintering” and “duplication” depleting a developing country’s already limited resources. He also wanted universities to explore research projects as a team, to ensure Sri Lankan academia was thorough, insightful, and of a high enough calibre to be published in top peer-reviewed journals.

Without such opportunities, many Sri Lankan scientists were—and still are—lured to the West by lucrative careers in science. While nothing short of high-paying and fulfilling research opportunities at home will stop the ‘brain drain’, there are temporary, short-term, and small-scale ways to minimise the number of people who leave Sri Lanka for research yearly. In his time, Ponnamperuma sought to mitigate these losses by cultivating personal relationships with those students he and his colleagues at the NIFS groomed for studies abroad. This grassroots approach is what inspired Prof. Seneweera—a protege of Ponnamperuma from 1987—to direct his academic talents homeward, despite his postgraduate career initially taking him across three continents.

Image courtesy: Prof. Saman Seneweera

From academics to advocacy, Ponnamperuma was a visionary concerned with the trajectory of life in both directions, back to our chemical beginnings and forwards to our technological future. Despite international acclaim and local reverence, it was Ponnamperuma neither as a researcher nor an activist, but rather as an individual, that has been immortalised in the psyche of a generation. The drive to take Darwin’s theory and ask “What about before?” and the optimism to push Sri Lanka to scientific modernity are what remain pertinent in the minds of those he influenced. “The lasting legacy of Cyril Ponnamperuma is not the research papers he published, or the PhDs he supervised, or the thousands of students he taught,” Gunawardene remarked. “That was all significant—but as far as Sri Lanka is concerned, it’s the inspiration he provided to a generation of young people, young researchers in the ‘80s and beyond to pursue careers in science and technology.”