When Reeza Zarook, founder of Rukula, used to work at anything.lk—Sri Lanka’s first daily deals and e-commerce online store—he noticed that many of the customers who walked into the store’s physical space down Thimbirigasyaya Road were not regular e-commerce clientele. They were an eclectic mix of people from lower income brackets, often three-wheel drivers from the stand across the street, just stepping in when they noticed the advertised deals.

“They’d ask if they were also allowed to buy things, despite not having a [credit] card, and I’d tell them, yes, of course you can!” he said.

However, their next question would often put the proverbial wrench in the works: they wouldn’t have cash in hand, but wanted to pay in instalments nonetheless. This was not a service that the store offered.

The people who walked in were mostly daily-wage earners who couldn’t make large payments in one go, but needed to buy regular items like gas cookers or mobile phones. Most of these potential customers neither had guarantors or collateral to put forth before banks, nor did they need large loans; their requirement was to simply purchase goods on credit. According to Zarook, this section of ‘unbanked, no-digital-footprint’ customers make up 40% of Sri Lanka’s population— which is quite a sizable percentage.

Noticing an overlooked customer base, Zarook then pitched the idea of whether the company could create a payment scheme for this clientele.

“The Board said no because we’re not a finance company,” he said. “So when I left [anything.lk] in 2014, I decided to look into how we could help them.”

What he came up with several months later was a unique concept: a company which would sell products on credit, without collateral, and without charging interest. The company would sustain itself by having higher profit margins instead.

Expecting The Best, Preparing For The Worst

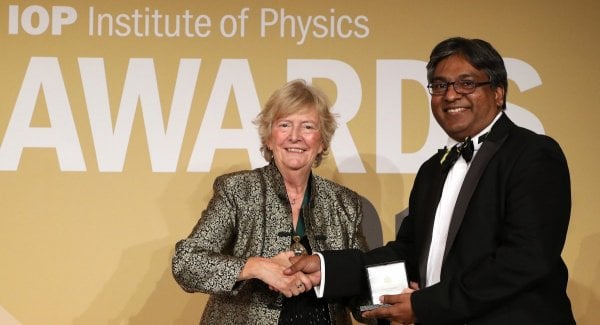

After noticing how most of Sri Lanka’s unbanked citizens were unable to buy household goods on credit, Zarook came up with a unique concept.

Photo credit: echelon.lk

Zarook began in what he calls the “typical start-up fashion” — by spending weeks on end taking up what he said was one of the best seats at Whight and Co., the cafe in Colpetty that overlooks the Indian Ocean.

He first looked at what sort of institutions offered loans, and what their terms and conditions were. He found that finance companies were a ‘bit more unscrupulous’ but were happy to lend money if it was needed to purchase something big, and of resellable value. Next up, he thought about microfinance schemes, which have been around for approximately 35 years, and cater to a South Asian market. However, these had multiple conditions as well..

“Over 35 years of microfinance and the basics haven’t changed much,” he said. “The microfinance institutes prefer a group of borrowers, who are micro-entrepreneurs, preferably female, and the most important thing is that the money you’re borrowing should be used to generate more money — it should be used as working capital or on income generating assets,” he explained. This was precisely what Zarook wanted to change: the culture of having to show capital, collateral, and investment plans, and of choosing whom to lend to. There tends to be an arrogance among educated people, he said, that assumes that poorer people do not know how to spend money.

That, in a nutshell, was how Rukula was born. The fundamental belief that guides the company is that people are inherently good, and that no one is inherently bad. Based on experience and ground realities, the company also built it into their models that their customers would probably have a ‘financial crisis every other week.’ This is not necessarily anything major by definition, Zarook said. It could simply mean that a three-wheel driver’s trishaw needs repairs, or that a fisherman gets sick. That would imply that money would be scarce for the family concerned for that week.

“…because we know this, we don’t stress about it,” he said. “But we do have a sales contract with them. And no matter what happens, we won’t take more than 10% of their income at any given time.”

How Does It Work?

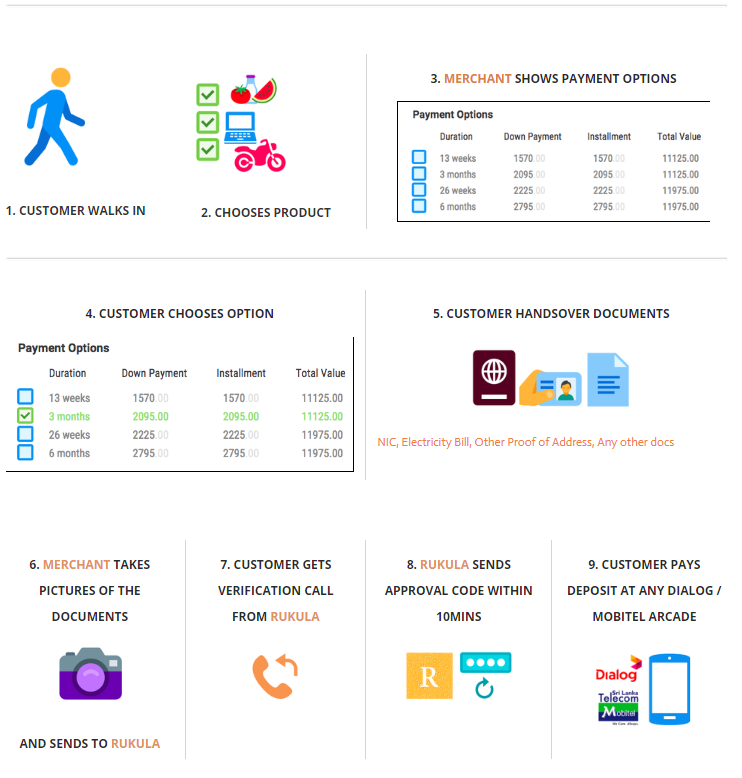

The process is relatively simple. Rukula looks at several different attributes of their clients, not in terms of their financial stability, but in terms of their familial stability. They plug in all the information they receive from potential clients into their system, and begin the process.

With around 250 merchant stores, most located in the Western Province, the customer simply has to fill out an online form to begin with — and this is more often than not done by the merchant. The only thing the customer needs to bring along is a national identity card and proof of residence, which could simply be an electricity bill or along similar lines.

Graphic credit: rukula.lk

The merchant vendor then sends a picture of the documents to the team at Rukula, who immediately follow up with a phone call to the customer. There are a few preliminary questions verifying their interest in the product, with several informal questions (matrimonial status, age and such) thrown in. Once the necessary personal details are acquired, the customer’s request is approved, and they are guided through the payment process — which is made through any Dialog or Mobitel payment platforms.

An initial down payment of 25% has to be made, and the rest is on a monthly basis.

However, there are a few restrictions: the items purchased have to be under Rs. 30,000, and the range of products offered do not include jewellery, clothes, and prescription drugs.

Bridging The Digital Divide

One of Rukula’s best customers is Govindan Ganeshwari. She has bought six items through them, and made all payments on time as she wants to maintain the trust between herself and the company.

Image credit: Rukula.lk

Rukula has made profits since 2016, and are now able to form partnerships with much more ease. “We grew 400% over the last year,” Zarook said.

“When we started out in 2015, we had to hit the road and persuade people to sign up. Now, we give merchants a target they have to sell at least three items a month, and there’s a refundable deposit they have to pay if they want to work with us.”

The merchants are also given basic training on how to use the app, and close sales.

While the company wants to expand and become more accessible, the goal is to have a wider reach, not more sales. They also want to make health insurance accessible to their clientele, and as a first step towards achieving this, Rukula has partnered with oDoc—a digital medical consultation platform—to provide all of Rukula’s customers and merchants unlimited access to the healthcare app.

Though the customer signs off agreeing to pay back by the end of six months, they usually take about 18 months to do so — and a very small percentage, if at all, default on their payments. The trust basis seems to work, which is why the company strives to create a bond with their customers, and take their circumstances into account. The relationship works both ways, as customers strive to maintain the trust placed in them by Rukula by paying their dues in a timely manner.

“If you treat people with dignity,” Zarook said, reiterating his previous point that no one is inherently bad, “they will reciprocate.”