In an attempt to curtail the Kandy riots which flared up on 04 March, the government issued directions via the Telecommunication Regulatory Commission (TRC) to restrict internet access. The order was sent directly to Internet Service Providers (ISPs), and was implemented with immediate effect in the early hours of 07 March.

Despite government officials initially stating that the restrictions were only on for 72 hours, it lasted for over a week. Viber was restored on the 14 March, with access to WhatsApp being restored a day later. On 15 March, President Maithripala Sirisena also tweeted that he ‘instructed’ the ban on Facebook to be removed with immediate effect, which it was, several hours later.

Why Restrict Social Media?

Defence Secretary Kapila Waidyaratne revealed there were new inclusions in the state of emergency regulations. Image courtesy: onlanka.com

Presidential Secretary Austin Fernando claimed that the government instructed the TRC to implement internet restrictions so that the situation would not spiral out of control.

“The public can see the type of content that is widely shared, and the effect it has on the current situation,”he stated, adding “fake news” which was being circulated across social media sites could possibly trigger “further instability” across other parts of the country.

While access to the internet is now considered a basic human right, these can be suspended under the state of emergency. According to the Ministry of Defence Secretary, Kapila Waidyaratne, the state of emergency imposed over the last month had new inclusions, which will “assist the security forces and police to arrest the situation.” Under the section outlining offences and penalties in the latest gazette notification which declared the state of emergency, using social media to spread false statements or rumours could lead to arrests.

Addressing Racism And The Freedom Of Speech

At a forum discussing internet restrictions on 13 March, the Internet Society of Sri Lanka (ISOC) voiced concerns about the restrictions, and how it failed to address the root cause of racism.

Many pointed out that hate speech did not begin online, and it was of little use to restrict internet access if nothing was done to curb racism.

“There are no laws against fake news, but there is legislation against hate speech. The government could have implemented that instead of going for a state of emergency,” Owner of Ants Global, Engineer Thilak Dissanayake said.

One of the founding members of the ISOC, Dr. Kavan Ratnatunga, pointed out that most government politicians do not understand the internet.

“If you don’t know how to use it positively but other groups do, that’s a problem. Rather than rising up to use technology, just blocking it isn’t a solution…like until recently, Tamil News was blocked—and I don’t know what reasons are used to justify blocking political sites because that’s basically blocking free speech,” he said.

Other participants at the forum pointed out there was a difference between social media sites and instant messaging networks, both of which were blocked indiscriminately.

It isn’t just the ISOC and its community members who were worried about what the restrictions implied—Transparency International Sri Lanka (TISL) was also concerned.

In a statement, TISL highlighted that the move to restrict social media contradicted the government’s commitment to free speech. The organisation pointed out that while the move may have been well-intentioned, preventing the information from flowing freely was not the method to address “deficiencies in maintaining law and order”.

TISL’s Executive Director Asoka Obeyesekere stressed that the government should focus on apprehending those responsible for spreading hate speech, instead of blocking communication tools.

Not Just Free Speech

Small businesses and startups claimed that the extended restriction on social media and messaging apps caused immense damage to their operations. Image courtesy: goodmarket.lk

In addition to communication being limited, blocking Facebook and Instagram heavily affected small businesses and start-ups.

Kraftsy, a handmade footwear store, stated they faced a loss of approximately Rs. 20,000 for each day Facebook and Instagram were down. According to the store’s co-founder Crystal Koelmeyer, about 60% of her profits are from Facebook.

It wasn’t just home businesses that suffered. The Good Market, a self-financing social enterprise connecting vendors with buyers, had two aspects which were affected: their vendors, and their day-to-day operations.

“Most of our vendors are start-ups and Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs),” the Good Market co-founder Achala Samaradivakara said. “They don’t have a separate budget for marketing and use Facebook and Instagram as their ecommerce platform. The restrictions really discouraged them—I know their e-commerce was down, and daily promos were down,” she added.

Pointing out that the government is supposed to be supportive of SMEs and cottage-run businesses, Samaradivakara reiterated that shutting down the sites made both the Good Market and their vendors miss out on marketing their produce.

“I know there is a problem in the country and the government needs to take action, but is this the right thing to do? They should have a mechanism to identify the troublemakers and apprehend them, instead of having hundreds of small vendors who are trying to make ends meet, suffer,” she said.

Discussion And Results

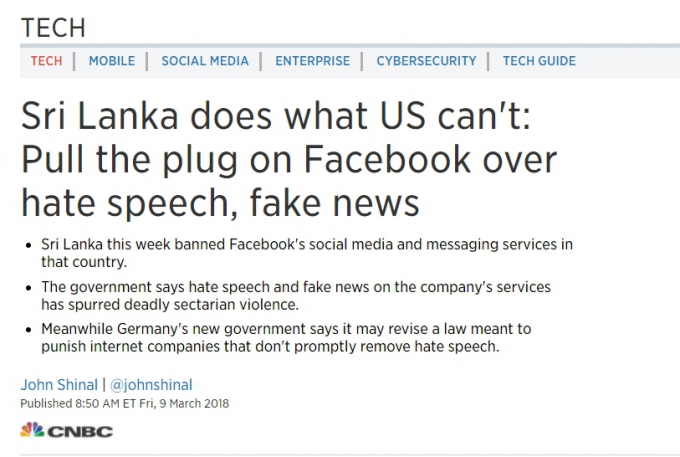

International headlines compared Sri Lanka and the USA’s approach towards hate-speech. Screenshot of cnbc.com

The government’s decision to block Facebook made headlines worldwide, some claiming that Sri Lanka did what the USA couldn’t, which was to “Pull the Plug on Facebook Over Hate Speech, Fake News”.

Within a week of the ban, Facebook officials flew down to Sri Lanka and met government officials, among several other organisations.

Following the discussions, President Maithripala Sirisena tweeted that “On my instructions, my secretary has discussed with officials of Facebook, who have agreed that its platform will not be used for spreading hate speech and inciting violence. As such, I instructed TRCSL to remove the temporary ban on Facebook with immediate effect”.

Official statements of the discussion are yet to be released. However, several civil representatives were also in touch with the Facebook delegation, and had discussed the matter via call last Friday (16). Sources stated that the delegation affirmed they would work against hate speech and racial violence, but not defamation.

Meanwhile, according to data from 2016, Facebook has been banned in eight countries. Whatsapp, the instant messaging app, is banned in 12 countries. However, Facebook-related user arrests are higher. The Business Insider states that 27 users from around the world were arrested as of 2016.

Key findings from freedomhouse.org highlight that globally, 27% of all internet users live in countries where people have been arrested for their Facebook activities; be it publishing, sharing, or simply ‘liking’ a post.

Cover Image courtesy: Realradio.lk

.jpg?w=600)

.jpg?w=600)

.jpg?w=600)