During most crises, the effects felt are uneven. The repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic have been twofold; a direct result of the crisis as well as the state’s response to it. While the lockdown has been a measure implemented to mitigate the threat of COVID-19, it has produced unintended consequences and circumstances that are yet to be addressed.

In Sri Lanka, the efforts to control the spread of the viral disease, implemented since March, have challenged the livelihoods and lives of several vulnerable groups. It has already created casualties of an extended curfew period for whom ‘staying at home’ can mean unbearable pangs of hunger or abuse behind a closed door. The casualties are not just economical but also physical, social, and emotional.

At Roar Media, these stories have been—and continue to be—shared and recounted on our social media. Here we compile and curate, providing a brief snapshot into the lives of many.

Street Cleaners and Garbage Collectors

Gamini Indralal (55) drives a garbage truck for the Kotte Municipal Council. “We are essential workers, so we have to work during curfew too,” he said, washing his hands with a bar of soap which he now carries around, after the COVID-19 outbreak.

Equipped with the mandatory face mask and gloves, Indralal and his fellow workers are on duty, working their respective garbage collecting routes. “Our salaries are paid. The cleaners are also showing up for work,” he said.

“When the lockdown was announced, I could have gone home to Kurunegala where my family lives,” Indralal said. “But I chose not to. It’s better to stay in Colombo. We get food and a bed to sleep in. And I send money to my family. It’s not so bad.”

Domestic Workers

“Most families who employ domestic workers do so to help them with their own workload. Now, with everyone home, and finances uncertain, be it middle-class or lower-middle-class, the need for a domestic worker is less,” Menaha Kandasamy, founder of the Domestic Workers’ Union (DWU) told Roar Media.

After curfew was imposed, domestic workers could not travel to work, and many who reside at their employers’ houses were asked to return to their hometowns.

“No money means no food,” explained part-time domestic worker and President of the DWU, Sarasgopal Satyavani. “Even if they [food lorries] bring food to our area, everyone struggles to purchase something,” she said.

Domestic work in Sri Lanka is severely unrecognised and excluded from several labour laws. Although the union has been lobbying for laws that benefit the workers, Kandasamy fears that in the light of this crisis, the process will be delayed further. “The workers face not only short-term but also long-term consequences,” she added.

“In a situation where our employers themselves are struggling to keep their jobs, I do not know what kind of work will be there for domestic workers in the future,” Satyavani said.

Victims of Child Abuse

The National Child Protection Authority (NCPA) has observed a rise in reports of child cruelty, following the COVID-19 lockdown.

“During this time that curfew has been in place, the NCPA’s 1929 hotline has recorded 352 complaints,” Professor Muditha Vidanapathirana, Chairman of the NCPA told Roar Media. Out of this, 152 complaints are of cruelty, where children are victims of physical and psychological trauma at their own homes.

While previously, complaints of abuse were not always restricted to domestic environments, reports during lockdown are different.

“Before the curfew, the NCPA received roughly 40 complaints a day, out of which four of them were cases of cruelty against children. What happened during the curfew month (17 March – 17 April) was a significant increase in that. We noticed that cruelty cases went up to six cases, out of the 10 complaints we received every day,” he noted.

Just during this period, the percentage of child cruelty cases reported to the NCPA have increased from 10 to 60 percent. It is likely that many more go unheard.

Three-wheeler Drivers

Shihan Fareed (47) is known to many as ‘Thilas’ in his village. Usually, he wakes up early in the morning to take his children to school, before starting his work driving his three-wheeler.

“Sometimes I get hires soon after, but at other times I have to wait for a while. Depending on the day, I can earn between Rs. 2,000-2,500 on average,” he said. “Sometimes more, sometimes less.”

These days, Thilas has no income due to the lockdown in place. He lives with his wife, four children, and mother. His oldest daughter’s husband (currently a trainee at the post-office, earning a small stipend) and child also make up the entire household. As the sole breadwinner, he has had to depend on donations and help from neighbours, friends, and relatives.

“We all live in the same village, and consider ourselves one and the same,” he said.

Day Labourers

Sarath* (62) is a labourer attached to the Kotte Municipal Council. He was paid his last salary by his employer, but other benefits and overtime payments had been cut off. “The first week of curfew was really difficult. We were supposed to receive aid from the naghara sabha (municipal council) but we didn’t,” he said.

As an essential worker attached to the Municipal Council, nowadays he occasionally gets called into work, without any remuneration. He also used to clean houses regularly in order to earn some extra money. After the lockdown, however, this too has come to a halt.

Sarath and his wife live in Bandaranaikepura, Rajagiriya. Their son, Malith*, told Roar Media that it was impossible for his parents to buy anything even when the food lorries started coming in. “Whenever the lorries came it would only go to some houses. By the time it reached us, everything was over,” he said.

However, things changed over the next few weeks, and goods were made available to everyone.

“Right now it’s manageable,” Malith said.“But what happens when we run out of money? How are we going to buy anything from the lorries? There are so many families in Bandaranaikepura who are already facing this situation. If the lockdown continues, what is going to happen when my family has no money to buy anything?”

Pensioners

Nimali Jayawardana (83) receives two pensions, both of which belonged to her late husband. One is for his service as an officer in the Sri Lanka Army. The second, for his work at the United Nations office in Sri Lanka.

“On a normal day, amma would receive her first payment to the post office and the other one would be deposited to her bank straight away,” Jayawardana’s daughter, Crishanthi told Roar Media. “This time, it was different.”

Due to the lockdown in place, the Sri Lankan government implemented a strategy to hand-deliver the payments to retirees and their families via postal officers on 2 and 3 April. “Amma received that payment, from which we purchased her medicine. But it was not enough and she has a doctor’s appointment coming up soon. We were hoping to receive the other pension allowance as well, but we don’t think it will arrive anytime soon,” she said.

Factory Workers

“The first few days of curfew were really difficult,” Mala* (27), a factory worker at the Katunayake Export Processing Zone, told Roar Media. “I kept wondering if the food we have in our room was enough, but I was grateful that we had water to drink,” she said.

When curfew was first imposed, among the many stranded away from their hometowns were workers employed at garment factories, living in boarding houses within EPZs.

A week after, transport was provided for these workers who wished to travel back home. Some chose to stay behind and since then, have returned to work amidst the lockdown.

Currently, a few factories have reopened, after adopting new safety measures against the COVID-19 crisis. Mala is waiting to hear back from her company so that she can go back to work. “I was paid for March and April, but was told that May depends on my willingness to come into work,” she said.

However, not all workers have continued to receive a salary. They wonder about the months to come, as they form an integral part of the country’s apparel sector—estimated to be one of the hardest hit in the current economy. Tap the link in our bio to learn more about the uncertain wage of factory workers, in Sri Lanka.

Victims of Domestic Violence

Ever since the COVID-19 curfew was imposed, non-profit organisation Women In Need (WIN) has observed an increase in domestic violence reports. With over 450 calls and an increase in new callers, 75 percent of calls received are from victims of domestic abuse.

“Domestic violence is not a new issue. But, where there is a curfew, with financial and social pressures, children at home, and no travel—it is worse when you are locked in with an abuser,” Project and Legal Manager of WIN, Mariam Wadood told Roar Media.

In addition to counselling services, WIN works with the Police to intervene and when possible, transport victims to three shelters in Matara, Batticaloa, and Colombo. However, the organisation faces challenges of its own; with travel restrictions, limited number of shelters, and a law enforcement directed at tackling the COVID-19 crisis. In addition to reports of domestic abuse, the organisation receives calls asking for rations, general assistance, legal advice, custody-related queries and reports of cyber harassment.

Wadood pointed to how stereotyped roles of men and women play a large role in the rising trend of domestic feuds and violence. “There are expectations of each gender, for example, the women must cook and clean, and these roles are not flexible,” she said.

She also noted that at a time where violence against women is exacerbated, the availability of only an ad-hoc system to support victims of abuse becomes more pronounced.

Textile Shop-owner

Ramanathan (50) is from Kandy, but owns and manages his own cut-piece textile shop located on Negombo Road. It is his main source of income to support his family who lives back in Kandy.

He used to visit them occasionally whenever he could catch a break. But ever since the COVID-19 curfew began, he has not been able to travel home and has been confined to his shop. It was during this time that he decided to start stitching masks and gloves using the material he had stored at the shop. His son too has been assisting him, and with the shop closed for sale, he thought this could generate an income for the both of them to survive on.

Ramanathan also felt that by selling these items at a reasonable price where there is a demand for it, he would be providing a service to the community. With permission obtained from the Police, he managed to set up his three-wheeler to sell his products to the public.

People travelling along the Negombo Road stop by to buy these masks and gloves from him. He also sells braided ropes which are used to hold down goods when transporting. According to Ramanathan even the little money he makes out of this, he is unable to send to his family due to his banking limitations. He has registered with the Police with the hopes that they will soon allow him to travel to see his family.

Report by Nazly Ahmed

Lack Of Access To Basic Resources

For some citizens in Beruwala, water comes in short supply for half a year. “During the sunny season we don’t receive water,” resident Sharmila* (19) told Roar Media. Even though Sharmila is currently in Colombo, she communicates regularly with her family who has been struggling to receive water.

During the drought season, some houses in the neighbourhood open their private wells for others to use. However, after the COVID-19 pandemic, most neighbours have stopped allowing others to come into their homes. “They tell us that we might bring in the virus,” she said.

Usually, the community works together to arrange a water tank at a specific location for everyone to use. “When this happens, we can get around 10 litres of water to our houses by paying a three-wheeler to bring it for around Rs. 200-250. Alternatively, we can walk and go, though this takes around two hours or more,” she told Roar Media.

“After the curfew was imposed, some members of the community began working together to distribute four litres to each house. But we are expected to make this last for four days,” she said.

The majority of Sharmila’s neighbours are daily wage earners. “Initially they did not receive essential food items and most ate half a jackfruit for each meal in order to survive,” she said. “Now things have improved with some receiving rations, though not all. The main issue is securing a steady flow of water, which remains unresolved.”

The Homeless

On 17 April, nearly 300 homeless individuals in Gunasinghepura, Pettah were taken to quarantine centres outside Colombo, after fears of COVID-19 spread through the area. The programme led by the Police and public health officials saw the group of homeless being disinfected and washed before being transported to the centres. New clothes and food were also distributed among the 300 men and women, who usually engage in begging.

Many of them later tested positive for COVID-19. Those who had contracted the disease were immediately sent in for treatment. The others, after completing the quarantine period, faced the conundrum of having no home to return to.

“I received a call from the Department of Social Services of the Western Province asking if we would be willing to take in a group of homeless elders who were quarantined in Mullaitivu,” Sanath Munasinghe, founder of Shelter4Homeless—a privately funded shelter for homeless senior citizen—told Roar Media.

“They were begging on the streets when they were taken to quarantine. And now they have no home to return to. Our institution agreed to take 10 of them, provided the state fulfilled some requests,” he said.

According to Munasinghe, since the COVID-19 lockdown, private run homeless shelters have faced complications due to diminishing stocks and the inability to transport or properly care for their residents. “We have 17 homeless elders under our care at the moment (without the group from Gunasinghepura) and we mostly work with private donations,” he said. “If one of the residents had fallen ill, we would not have been able to take them to the hospital because of the curfew. Apart from that, there has been little to no help from the Social Service Department until now.”

Munasinghe noted that the Department has agreed to support the shelter whenever residents require medical attention. Similarly, the Department would also be responsible for arranging funeral arrangements at the cost of the state, in the case of a death.

Prisoners

“During the COVID-19 crisis, restrictions were placed prohibiting visitors, and inmates were not allowed to receive additional necessities such as soap, clothing, sanitary napkins, etc.,” President of the Committee to Protect the Rights of Prisoners, Senaka Perera told Roar Media.

On 21 March, a riot at the Anuradhapura prison resulted in the death of two inmates while six were injured. Reports have been mixed; some claiming the prisoners were protesting visitor restrictions and others stating that tensions were due to suspicion an inmate had tested positive for COVID-19.

Overcrowding in Sri Lankan prisons is not a new issue. 2018 Prison Department Statistics reportedly* estimated overpopulation at a whopping 73.3 percent — a large number of these pre-trial detainees.

In March, activists called for eligible prisoners — arrested for minor crimes or those awaiting trial — to be released on bail. They also asked for particularly vulnerable prisoners, like women with children, the elderly and the sick to be released on bail.

Assessing the situation, the government released over 2,900 prisoners on 5 April on bail.

“The prisoners receive their basic needs,” Perera said. He said, however, that the current crisis had prevented them from receiving small but important benefits and exacerbated existing structural issues within prisons and the criminal justice process.

Children At Care Homes

There are 374 child care institutions in Sri Lanka, managed by the provincial commissioners of the Department of Probation and Child Care Services (DPCCS).

“Approximately 12,000 children live in these institutions,” DPCCS National Commissioner Chandima Sigera told Roar Media.

“Among the many problems the department had to deal with was the lack of food and essential goods after the lockdown,” she said, explaining that some department officers were unable to procure curfew passes to travel between districts for their work.

“But whenever these matters came up, we worked together and resolved them,” she said.

The Department also received reports of various charity frauds committed by unscrupulous individuals wanting to make money off this situation. The fraudsters would collect public monies under the pretext of helping the child care institutions—without the knowledge or sanction of the DPCCS.

“We ask the public that while donating to children is a valued effort it would be best to verify beforehand,” she said. “There are so many scams like this out there, where people ask for money to be donated to orphanages, but the child care homes never receive them.”

These frauds are under Police investigation.

Farmers

Farmers, bee-keepers, kithul planters — these are just some of the people affected greatly by the curfew that was imposed as a result of COVID-19.

A group of young greenhouse farmers from Welimada, Uva Paranagama, Bandarawela, and Hali-Ela said the curfew had prevented them from selling their produce.

The farmers are part of a Department of Agriculture-led programme that provides concessionary loans to build greenhouses and cultivate tomato, cucumber, and bell peppers.

“Before the COVID-19 crisis, a kilo of tomato was sold at Rs. 130-140, a kilo of cucumber at Rs. 200 and a kilo of bell pepper at Rs. 850,” Gunadasa, a field officer overseeing a number of the farming projects in the Uva Province told Roar Media.

“But during the lockdown, we couldn’t even sell a kilo of bell pepper for Rs. 30. No one bought the harvest.”

He explained that 100 farmers are participants of the programme, of which 59 had received loans and 35 had used it to cultivate their first season when the curfew came into effect.

Although agriculture was not prohibited during curfew, the farmers found it difficult to sell their crop to the local market.

“Our farmers faced a desperate situation,” Gunadasa said, explaining that these crops were typically sold to a different clientele at supermarkets.

With wholesale marketplaces in central areas and other economic centres scattered across the country temporarily shut down, farmers began selling their produce on the roadsides.

In April, the government intervened and purchased over 700 metric tonnes of vegetables sold by roadside vendors.

L. K. Priyantha (49), is the Managing Director of Lanka Eco-Products, and oversees 500 kithul treacle producers, 350 mushroom farmers, and 300 beekeepers — all of whom, he said, were unable to sell their produce during the curfew.

“Our main clientele were cake-makers, wedding receptions, and hotels. But now with everything being cancelled our sales have dropped immensely,” Priyantha told Roar.

“We had to resort to new ways to deal with the situation such as implementing a mobile unit that would go around selling the produce.”

“Even after the curfew, we still face trouble selling our products because people only buy what is necessary,” he explained further.

A Contractor Turned Essential Worker

Mohamed Faris is a building contractor who lives in Panadura. He usually undertakes contracts from his hometown as well in areas nearby such as Dehiwela and Mount Lavina. However, during the COVID-19 curfew all of his construction projects were halted.

Out of options to support his family, he began selling essential food items. Having obtained permission to transport goods in his three-wheeler, he began making visits to the Pettah and Manning Market almost three times a week to purchase everything that he needed.

He would then sell them at a reasonable price to the people in his neighbourhood.

“I can’t sell with a big profit margin,” he said. “I should be reasonable at a time like this. And after all the costs are counted, I am left with a very small amount. But it keeps me going.”

Report by Nazly Ahmed

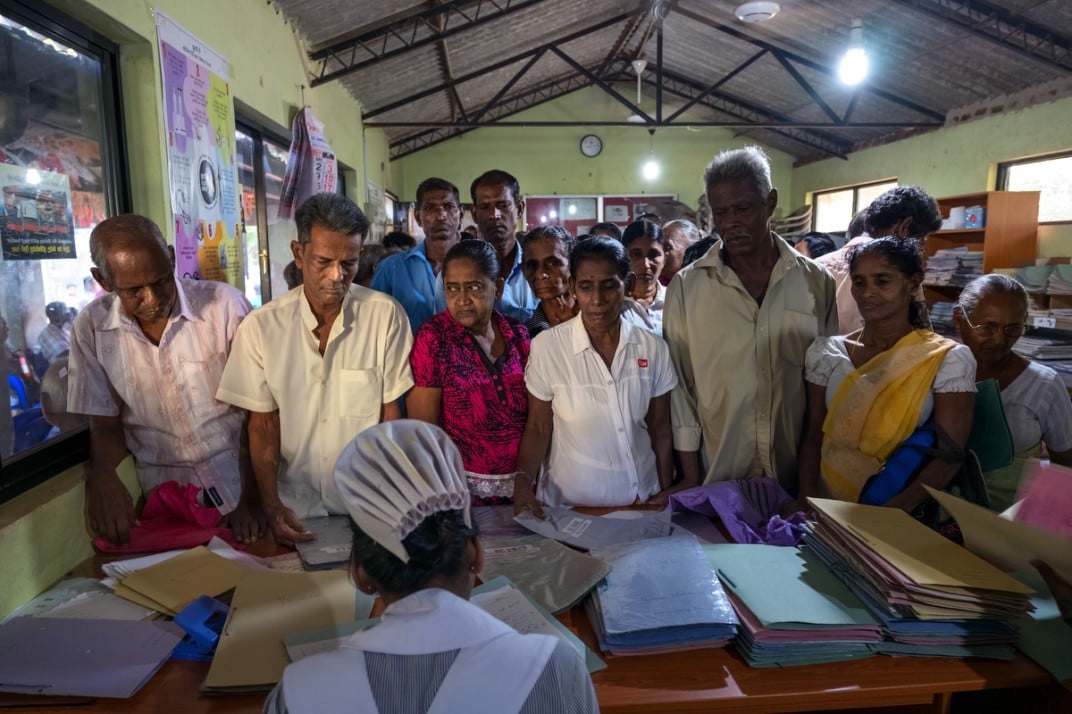

Chronically Ill

With medical resources exhausted as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, access to general healthcare has been a struggle—in particular for many with chronic illnesses.

Asoka Liyanage (68), a kidney patient, was left stranded with no access to regular dialysis when his usual private hospital was shut down after a false COVID-19 scare in April.

“All the other private hospitals refused to take us in. Government hospitals said that they could only accommodate some of us for a short period of time,” his son, Suneth told Roar Media.

“My father had trouble breathing. He was supposed to have his treatment on 21 April, but couldn’t,” he said. It took six days for authorities to reopen the hospital and offer services to the patients: that too, only after a massive public outcry.

With primary attention diverted towards containing and treating the novel coronavirus, patients suffering from diabetes, cancer, and other chronic illnesses have had to adapt to the current situation.

Fishermen

Ponnambalam Udhayakumar (45) started fishing at 15 years old, with his father. Thirty years later, he still goes out to sea to earn a living. Only a small percentage of the income is kept for himself, and the rest is spent on the boat he hires.

Although no restrictions were placed on fishing during the COVID-19 pandemic, the livelihoods of many fisherfolk were nevertheless severely affected.

Udhayakumar told Roar Media he was not able to sell his catch to his usual customers or wholesale purchasers because no one came to buy them. “I had to sell everything I caught at a very low price by the side of the road. It was not even close to the income I received before,” he said.

According to Udhayakumar, a kilogramme of any type of fish could be sold at Rs. 400. But during the curfew, this dropped to almost half, making it very difficult for him to make ends meet.

While Udhayakumar is away at sea, pushing off from the Trincomalee Bay almost every day, his wife tends to the household and their children’s needs. But with insufficient income from fishing, he has had to seek additional work elsewhere.

“[Because] the situation was so dire, I started undertaking small labour work. One person wanted help with the house they were building, so I became a mason’s assistant. The other time, I managed to clear some land for money,” he said.

Udhayakumar and many others like him were recipients of the Rs. 5000 allowance distributed by the government as relief during the lockdown, and he says the money was a respite from having to work menial jobs for a pittance.

“But we don’t know if we’ll get the money in the future. So I’m looking forward to going back to work,” he said.

Security Guards

“My work involves sitting on a chair for long hours in the night. I sleep in a small room the company has given me. That’s during the day, of course,” chuckled Mani* (52), a night guard at a restaurant in Colombo.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit Sri Lanka and businesses closed down indefinitely, security guards and night watchmen like Mani were among the few still working.

Even though many of those who continued to be employed opted to find a hostel or temporary boarding facilities in the city, Mani said he could not afford it. “I would have to spend half of my salary on the hostel,” he said. “I wouldn’t be able to send any money home. Here [in the security post], even if the room is small, I can manage. I get my food and sleep. I send money to my family.”

Mani had also initially planned to go home for the Sinhala and Tamil New Year in April. But with curfew imposed, he could not. “I haven’t been home in three months now,” he said.

Meanwhile, Siva* (58) who is one of three guards at a shopping centre in Colpetty lives at a hostel. “There are 18 others who stay here,” he said.

When the lockdown was initiated, the private security company that employs Siva cancelled all holidays for its employees. Siva said the company provided face masks and gloves to all staffers, as well as thermal scanners. At the hostel, they maintain distance from each other and have been instructed to use our own cutlery and to keep them clean and sanitised at all times.

“We were paid our salaries and were given rations to cook our food. If we were at home, we would not have an income. We would not have been paid. So we managed to live through the lockdown,” he said.

*—Name has been changed.

Disabled Community

While the unexpected disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic has caused grief to many, vulnerable populations and communities remain the hardest hit. Sumithra*, an amputee told Roar Media how hard she found it to go about her daily routine, even after the lockdown was lifted.

“I wear a prosthetic leg,” Sumithra said. “At supermarkets and other places, I’m expected to wash my hands using a station that is operated by foot. How am I supposed to do that?”

Marginalised even before the pandemic, the disabled community was significantly challenged during the lockdown.

“Visually-disabled persons who sell items by the side of the road, such as handicrafts and lotteries, to earn a living—they all lost their livelihood during the lockdown,” Rasanjali Pathirage, head of the Disability Organisations Joint Front (DOJF) told Roar Media. She added that the absence of a proper government database has made it impossible to ensure everyone received aid during this time.

Many of those disabled—most already dependent— had to lean further on volunteers, community supporters and rights advocates to survive.

Nalinda Nagolla, the Managing Director of the DOJF told Roar Media that over 2,000 persons from the community had problems buying food and dry rations and that approximately, 1,500 persons—mostly hearing-impaired—did not even receive the Rs. 5,000 allowance given by the government.

“Around 60 people suffering from physical disabilities—mostly, wheelchair-bound—couldn’t obtain their medicine and equipment,” Nagalla added. “Many didn’t even receive the aid and donations that were distributed because it was hard for them to stay in a queue to collect them.”

The DOJF, communicating through social media or online messaging platforms such as WhatsApp or IMO, managed to compile a database of complaints that were brought to the attention of the Presidential Task Force for Economic Revival and Poverty Eradication, which intervened to provide aid.

But although many of the complaints have been addressed after DOJF intervention, the disabled community continues to face challenges. “Even though the lockdown has been lifted, many are yet to receive their compensation. Funds approximately worth Rs. 290,000 have been allocated to provide aid, but they are yet to receive it,” Nagalla said.

Food Delivery Drivers

“We had no hires after the COVID-19 curfew was imposed,” Sisira* said.

Sisira, who works for an online food delivery platform is usually on the road for up to 16 hours a day, including on the weekends. But the COVID-19 lockdown completely dried up his source of income.

“It was quite difficult because we earn by the day and have little savings,” he said.

A father-of-three, Sisira and his family managed with what little savings they had. The company he works for also deposited a small percentage of his usual monthly earnings in his bank account, making things a little easier.

But managing those months under lockdown was still a challenge. “Food was the main problem,” he told Roar Media. “We had to think a lot about what we purchased.”

Food delivery apps have become quite popular in Sri Lanka. Delivery persons whizzing past in brightly-coloured jackets in all types of weather is now a common sight.

“We are quite used to the rain,” Sisira laughed. “Our main focus is on protecting our phones!”

Sisira returned to work when curfew was eased but has noted a low turnout of delivery persons, or ‘riders’ as they are known, as many have returned to their hometowns as a result of the lockdown.

Very few orders were also being placed, he said. This meant a smaller income than usual each month.

At work, Sisira’s temperature is checked regularly. He is given hand-sanitiser, a reusable face mask and educated on health guidelines he should follow.

‘Contactless delivery’, a new feature that allows the delivery person the option of leaving the food at the doorstep and moving away before calling to inform the customer, has also been gaining popularity, he told us. “But in some cases, there is no place to keep the food, even though contactless delivery has been requested, I can’t keep it near the drain!” he said.

Drivers are also now often held up at restaurants which are running on minimal staff, he added. Curfew that is still in place (between midnight and 4 AM every day) means that riders who previously had the option of working until 2-3 AM to earn extra have not been able to do so.

With limited opportunity, Sisira also wonders how he will fare the next few months, even as more riders return to work.

*Name has been changed