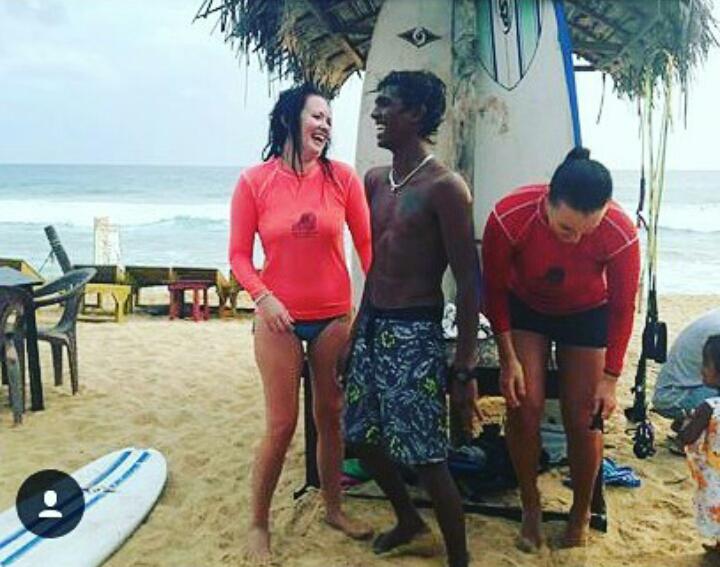

On the beach, sheltered from the sun under an awning, 22-year-old Ashan and his French girlfriend Sarah sat facing the camera. The couple were affectionate with each other, and continued a conversation in undertones, punctuated with laughter, until they were posed questions, which they answered seriously.

Sarah met Ashan in Unawatuna on her first visit to Sri Lanka, in 2016. She returned a year later to kindle a relationship with him. “We were just friends, and we talked. Later feelings started, and then this happened. Now he is my boyfriend,” the 28-year-old told us, snuggling up to him.

Sarah, who was employed in the hospitality sector in France, left her job to move to Sri Lanka. What will she do for work here? She said she plans to help Ashan with the diving centre he runs and perhaps help expand his business – maybe a restaurant, maybe more water sports, who knows?

On the surface, Ashan represents the stereotype of Sri Lankan men on the beach: he is a ‘beach boy’, with seemingly limited prospects and a foreign girlfriend, whom he plans to benefit or live off.

But watching Ashan share a simple meal of paan and curry with Sarah for breakfast, and the easy manner with which she mingles with his friends, who are also beach boys, indicates that there is certainly more to the story than meets the eye.

‘It’s Just A Name’

Ashan doesn’t view himself as a beach boy. He is just a boy who grew up on the beach where he runs a diving centre owned by his father, he said. He is referred to as a beach boy, not by the foreign men and women frequenting the beaches, but by the affluent crowd from Colombo, he explains.

Ranga, 22, agrees with Ashan. He too doesn’t perceive himself as a beach boy. “What is a beach boy?”, he asks? Walley kollo. Yes, we are boys that grew up on the beach. But this term beach boys is just a tag made up for us,” he said. “It’s just a name. It means nothing.”

I ask Ranga why he feels beach boys have such a bad rap. “It may be because we are counter-culture,” he said. “If a Sri Lankan woman spent all her time dressed in bikinis and on the beach, she would be called a prostitute. It’s the same with us. We are called names because we live a life that goes against our culture.”

But Ranga enjoys the freedom of his profession. “This is a free and easy life,” he said. As a diving instructor, he spends his days on the beach. He usually operates in Unawatuna, but when the southwest monsoon hits, he moves to Arugam Bay on the southeast coast.

Ranga is happy with what he earns, and says he would not trade his job for a ‘better-paying, normal one’. “We can’t be free in those jobs, like this,” he said. He acknowledged, however, that he was met with resistance when he first began to explore the beach as his primary means of living.

“My parents weren’t too happy at first. They wanted me to get a job inland, away from the beach,” he said. “But I wanted this life. I am passionate about the beach. I taught myself to surf and dive and took the exam to become a certified instructor. Now this is what I do for money.”

Ranga has never involved himself with a foreign woman. He said he had a local girlfriend, who was both understanding and supportive of his lifestyle. “She understands that just because we are surrounded by half-naked women on the beach, does not mean we are romantically involved with them,” he explains.

Indeed, not every beach boy is romantically involved with foreign women they meet on the beach. “It is connection-based,” explains Kumara, who has worked as waiter at restaurants in Unawatuna since 1989. “It is always consensensual, and in many cases, the women pursue these men that they find attractive and exotic.”

Rave Culture

Kumara also addresses concerns that frequent, drug-fuelled ‘rave’ parties are a hotbed for lawlessness. “Yes, there are parties every weekend,” he said. “And we have heard that the young people who come there take drugs. But from what I know, the drugs are brought from Colombo,” he said.

“Where would beach boys procure drugs that are smuggled into the country?” he asks, perplexed. “I have not seen anyone I know partake of this drug culture. It is mostly an elitist, Colombo posh-people practice,” he said, before adding brightly, “But we drink!”

Referring to reports of fisticuffs between locals and foreigners, Kumara replies that in his experience, such incidents occur when a foreigner hassles a woman involved with a local man. “If the woman is being harrassed, very often her local boyfriend will step in and even beat the foreign man,”Kumar said.

“Actually, it doesn’t matter if it is a local man or a foreign man. If a beach boy feels that his woman needs defending, he will defend her no matter the consequences,” he said. “There have been so many fights on the beach,” he reminisces, with a shake of his head.

Commenting on the well-publicised incident in Mirissa in April, when a group of Dutch tourists were assaulted for resisting sexual advances, Kumara said he had no insight. “We really don’t know what happened there,” he said. “But it is sad that things came to that level.”

Despite their defensiveness, though, there have been some reported instances of beach boys having run-ins with the law.

In May this year, in Trinco, two American women also reported being sexually harassed by a hotel employee.

A Variety Of Services

Krishmal is 26. His family runs a popular restaurant on the beach, and a nearby shop specializing in jewellery and other trinkets. Educated at one of the finest schools in Galle, Krishmal isn’t considered a beach boy, but he counts many of them as his friends.

“I consider the beach boys an asset to themselves, and an asset to the industry,” he said. “I don’t think they are doing anything wrong. They provide a service to tourists, at a nominal rate, and who cares if they end up in a relationship with some of them?” he asks. “That is up to them.”

I ask him if the waiters employed at his family restaurant are considered beach boys. “No”, he said. “These men have been employed based on experience and skill. They weren’t just hired – interviews were conducted, and the men most suitable for the job were hired.” .

“Also, there are rules here. But that is not the way everyone on the beach conducts their business. Some establishments are freer in their operations, and allow staff to fraternize with tourists. That’s their prerogative,” he said. In his view, the beach allows tourists a better chance to mix with locals.

“The beach is generally the last stop on a tourist’s itinerary,” he said. “This is where they come to rest, relax, and spend a few days. It allows them a greater chance to mix with the locals, than in the interior of Sri Lanka, where they only make a quick stop.”

Beach boys provide tourists with a variety of services, he told us. This could include a visit to the local bath kade or a guided tour of the town on the back on scooter. “The tourists establish friendships with these boys and often return as a result of that honest friendship,” he said.

“It is the same with locals,” he added. So many people from Colombo frequent this place, because they know people by name. They have visited their homes, shared meals with them. Locals, foreigners, it is is the same hospitality offered by the beach boys,” he said.

A Few Bad Eggs

So why do these beach boys have such a bad reputation? Krishmal shrugs. “A few bad eggs,” he offers. Pointing to lanky man on the beach offering foreigners a massage, he says, “That is another example of a beach boy,” he said, “but that is not what I would call a beach boy!”

A portly man passes us, colourful wood and cloth puppets strung on his arm. “Is he considered a beach boy?” I ask Krishmal. “ Technically, I guess, yes,” he grins. “But beach boys as I know it are typically young, sporty and attractive, and have interpersonal relationships with foreigners and locals.”

It is clear, despite the less-than-appealing reputation they have garnered that beach boys are not perceived as dangerous and threatening among those closest to them. This doesn’t mean there have not been incidents of concern.

In June last year, a British woman was left stranded in Sri Lanka after her husband was killed. Diane De Zoysa, 59, sold her house in Scotland and moved to Sri Lanka to live with Priyantha, a hotel worker she had met seven months earlier, but said she had had come to believe the marriage was ‘all about the money‘, and that Priyantha had another wife.

Professional Training

Krishmal is of the opinion beach boys will benefit from some sort of government recognition and training. “If they are trained on basic etiquette, dos and don’ts and other matters relating to the hospitality trade and industry, they will be able to work in a more professional manner,” he said.

He added that he didn’t mean the beach boys ought to be put in a uniform and made to wear a name tag. “That will take away their freedom,” he said. “But they definitely should be given some of kind of official recognition.”

According to Rasika Jayakody, Consultant, Communications at the Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority, the SLTDA is in the process of addressing these concerns.

“The SLTDA is in the process of formulating an island wide initiative, with the support of some volunteer organizations, to give beach boys training and recognition,” he said. Proper training and education will give them more opportunities to earn a better income and allow them to render a greater service to the tourism sector in more ways than one.”

.jpg?w=600)