A young physics major at the University of Southampton in the UK, Mahesh Herath (27), was always interested in astronomy. This interest may have been what precipitated his discovery of two exoplanets this year.

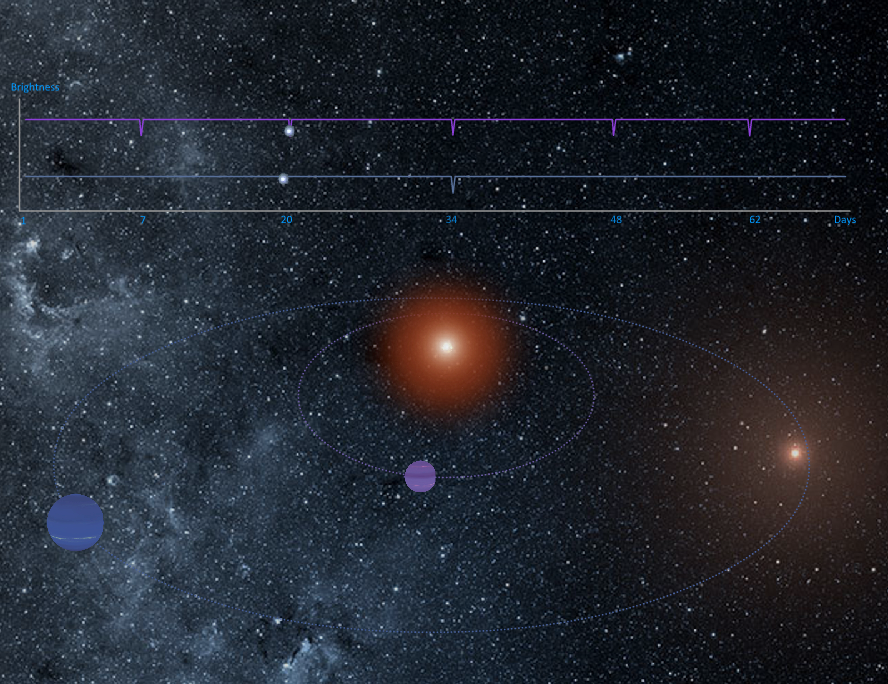

Exoplanets are planets that exist outside of our solar system, and observing one is a little more of a complicated task than observing a planet within our solar system. For their project, Herath and his friend located the star that the exoplanet orbited, and analysed the change in light emitted by that star over a period of three hours.

“You have to pay attention to the brightness of the star,” Herath explained. “When the planet crosses it, you can observe the light going down and then coming back up, which we managed to successfully do.”

This chance encounter with the cosmos would go on to shape the rest of Herath’s career. Today, he is an astronomer celebrated for leading a team of local and international scientists to successfully discover a system of exoplanets (two planets orbiting a star)—the first time a group of Sri Lankans have reached these heights in the field.

The discovery was published in the prestigious Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (MNRAS), and subsequently added to NASA’s exoplanet archive and the Exoplanet Encyclopedia.

Photo Credit: Sunday Observer

Shifting Perspectives

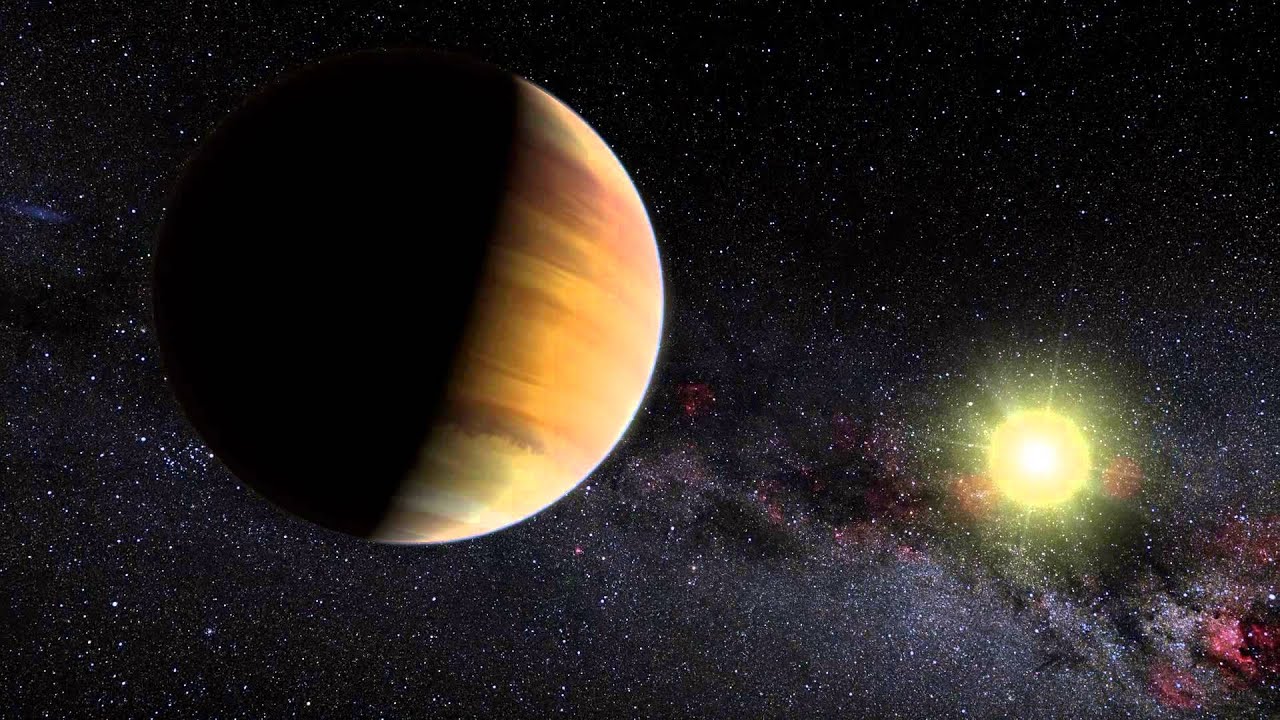

The planets, that have been named K2-310b and K2-310c, were found orbiting a star called EPIC 212737443, located 1,133 light-years away. According to Herath, it would take almost 50 million years to reach the planets using the fastest spacecraft launched from Earth.

“It’s not really a place that we can go to,” said Herath. “But building up this database is so important, because it gives us a bigger picture of the universe, and so much of what we know about planets has been transformed by finding planets outside of our solar system.”

Before the discovery of exoplanets, astronomers believed that most planetary systems were like ours, with small rocky planets like Earth orbiting close to their star, and giant, gassy planets like Jupiter orbiting further away.

But when the first exoplanet, Pegasi 51, was discovered in 1992, astronomers realised that although the planet was made up of gas, it was orbiting very close to its star. This contradicted the widely accepted fact that gasses can’t coalesce strongly enough to form a planet if it is too close to a star, as the wind and heat emitted by the star would blow it away.

“This threw a spanner in the works to every theory on planetary system formation,” said Herath.

Photo Credit: www.solstation.com

Several more planets of this nature—that have come to be known as ‘Hot Jupiters’—have been found since the discovery of Pegasi 51.

To explain this phenomenon, a theory that has been put forward posits that although gassy planets cannot form close to a star, they can migrate towards one, for a variety of reasons. This could be due to the gravitational pull of a second star in the system, or even a case of what Herath refers to as ‘planetary pinball’, during which unstable planets are ejected, and other planets in the system drift inward.

“But the question of how these gassy planets can remain stable while so close to their star…that’s something astronomers are still trying to answer,” said Herath.

The Next Steps

The system discovered by Herath and his team was in the sub-Neptune category of planets, which usually have thick hydrogen or helium atmospheres, though more research needs to be done to determine what these planets are truly comprised of.

And while Herath is curious and wants to explore this further, he is currently more interested in the way the planets are spaced out, as it does not fit neatly into modern astronomy theories.

“There is a theory that was formulated using statistics, that in most of these systems, the planets are very tightly packed,” said Herath. “What is interesting about this system is that there is a lot of space between the two planets we found.”

Photo Credit: Mahesh Herath*

One explanation could be that there were planets between the first and second, that were ejected out of the system. But it is also plausible that the orbit of these ‘in-between’ planets are tilted in such a way that the team has not yet been able to observe their transits.

To test these theories, Herath and his team made a simulation of the planetary system they discovered, to see if it was possible to have planets orbiting between. Their findings confirmed that this is possible, so long as the planet is very small.

There is still more to investigate and now that the two new exoplanets have been entered into international databases, further study is open to other scientists around the world. Herath, however, plans to focus on several other projects that he hopes will be published next year.

But exoplanets will be something he will always be on the lookout for.

“One of these days, someone will find an Earth-like planet close enough to our solar system, that could completely transform the way we interact with our universe—which is why we do what we do,” he said. “Aside from that, it is also really, really fun.”