The judiciary is the branch of government that determines whether the law has been violated. Though Sri Lanka’s current constitution does not effect a total separation between the legislature and the executive branches of the government, the judiciary is intended to function in complete independence.

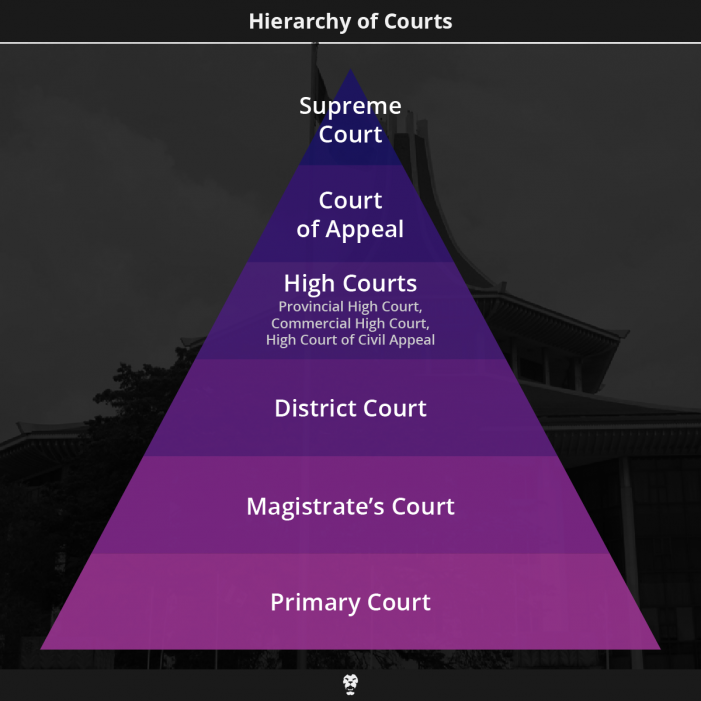

The judiciary is made up of seven levels of courts. A tiered system allows for a party before the court to keep appealing to higher courts—thus reducing the margins of error. Other than by rank of authority, the courts are also divided by jurisdiction. This is practically helpful, as it organises cases into specialised courts. More crucially, a hierarchy of courts is necessary in order to follow the legal principle of stare decisis. A feature of Sri Lankan Roman-Dutch law influence, stare decisis means “stand by decision”. In practice, it means that every court is bound to follow the examples set by every court before it. This ensures that the law is enforced equally to all, across all territories and generations. Having a clearly defined hierarchy of courts where each court abides by the decisions of the court above it, the precedents set by previous courts can be applied to cases with similar facts.

These are Sri Lanka’s courts of law, in reverse order of hierarchy:

Primary Courts

Primary Courts are the lowest in the hierarchy of courts, however, they are not necessarily a citizen’s first point of contact with the law. Established by the Judicature Act of 1978, a Primary Court has limited and specific jurisdiction over matters set out in the Primary Courts Procedure Code. Generally, a Magistrate serves a dual role as a Primary Court Judge, and there is no physically distinct institution as a Primary Court.

A Primary Court’s civil jurisdiction (where punishment is not a legal outcome) is limited by monetary value of the case. This would only cover disputes between private persons where the award of damages does not exceed Rs. 1,500. Where the civil case is minor, a Judge is expected to induce a settlement. It must be noted that such settlement, after both parties have signed the record, becomes enforceable and binding by law.

The criminal jurisdiction of the Primary Court is limited by its penal powers. This would only cover the following offences:

- Where punishment is no more than three months of imprisonment, either rigorous or simple.

- Where the penalty is a fine not exceeding Rs. 250.

The Primary Courts Procedure Code originally included whipping as an available punishment, however, this was repealed by an amendment to the general criminal law of the country. Even in cases where a Primary Court has exclusive criminal jurisdiction over a case, such case can be redirected to the Magistrate’s Court by the Attorney General, or any interested party by making an application to that effect to the Court of Appeal.

Perhaps the most frequently evoked power of a Primary Court is regarding disputes that fall under Section 66 of the Primary Courts Procedure Code, where a land dispute creates a breach of peace or an imminent breach of peace.

The Magistrate’s Court

The Magistrate’s Court conducts identification parades to identify suspects. Image credit: Cafker Productions/YouTube

The Magistrate’s Court conducts identification parades to identify suspects. Image credit: Cafker Productions/YouTube

A Magistrate’s Court is usually the lowest Court to try criminal cases. However, the trial of graver offences is reserved for the High Court. Section 9 of the Criminal Procedure Code gives the Magistrate’s Court the power to hear cases where criminal offences have been committed wholly or partly within its area of jurisdiction. The Magistrate’s Court will dispose of them summarily—that is to say only with the aid of evidence and the law, and not a jury. Just like the Primary Court, the criminal jurisdiction of the Magistrate’s Court is limited by its penal powers. Hence, this only covers cases where the maximum prison sentence—either rigorous punishment or simple punishment—is 18 months, and where the fine is no more than Rs. 1,500. It is the Magistrate’s Court that conducts identification parades.

In the exercise of its powers, the Magistrate’s Court will summon witnesses and issue warrants for the apprehension of suspects. A common way in which the average citizen comes across the Magistrate’s Court is in its exercise of search warrants. The Magistrate’s Court can issue warrants for places to be searched where the Court has reason to believe stolen goods or goods relating to an offence are stored.

Section 9 (b) (iii) of the Criminal Procedure Code also gives the Magistrate’s Court power to inquire into cases where a person is found dead under mysterious circumstances at a prison, mental hospital, or leprosy hospital.

Furthermore, in the event of graver offences involving the High Court, the Magistrate’s Court has the power to gather evidence by holding ‘non-summary inquiries’, or court procedures that do not pronounce a verdict. A party who is aggrieved by the decision of the Magistrate’s Court can appeal to the High Court, thereafter appeal to the Court of Appeal, and from there appeal to the Supreme Court.

The District Court

Known as the Family Court, it is the District Court that grants divorce. Image credit: Mike Kemp/Rubberball/Getty Images

Known as the Family Court, it is the District Court that grants divorce. Image credit: Mike Kemp/Rubberball/Getty Images

The modern day District Court is a descendant of the District Courts established by the Charter of Justice of 1833. According to J.A.L. Cooray, in his book Constitutional and Administrative Law of Sri Lanka, the forebear of the District Court had also exercised powers similar to the modern day Magistrate’s Court during the British colonial period. They had had the power, states Cooray, to “determine prosecutions for all crimes and offences except those punishable with death, transportation, banishment, imprisonment for more than twelve months, whipping exceeding one hundred lashes or fine exceeding £ 10”.

However, the District Court of today, set up by the Judicature Act, is deemed the “Family Court”, and has strictly civil jurisdiction. Unlike the other Courts, the civil jurisdiction of the District Court is unlimited, provided that a case that comes before the District Court has occurred in its territory of jurisdiction. All cases relating to marriage come under this Court. Hence, actions for divorce, nullity and separation, as well as the enforcement of their legal consequences, such as alimony, custody of children, damages for adultery, and corollary disputes regarding matrimonial property, are all addressed by the District Court.

In its role as the Family Court, given to it by the Judicature (Amendment) Act No.71 of 1981, the District Court will accommodate the special treatment given by law for cases that come under the Kandyan Marriage and Divorce Act and the Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act. The District Court shall appoint administrators in respect of intestate properties, or properties that have not been devolved by the deceased by way of a last will. Where a last will or testament is produced before the Court, it shall determine the validity of relevant documents and issue what is known as a probate, or the license to assume the powers of an administrator. Furthermore, the District Court shall also have custody over the estates of persons proven to be of unsound mind.

Unless jurisdiction has been specifically divested from the District Court, any dispute relating to contracts, testament, revenue, trusts and insolvency will come under it. A special category of cases excluded from the District Court are cases specified by the Intellectual Property Act and the Companies Act.

The High Court

It is the High Court that pronounces the death sentence. Image credit: Wikimedia

It is the High Court that pronounces the death sentence. Image credit: Wikimedia

The High Court derives its existence directly from the Constitution (Chapter XV). This is the highest court of first instance, or the highest court that determines cases, and has jurisdiction over all the graver criminal offences. Courts beyond this mostly have powers to hear appeals from lower courts. Section 9 (1) of the Judicature Act sets out the jurisdiction of the High Court as thus:

(a) any offence wholly or partly committed in Sri Lanka;

(b) any offence committed by any person on or over the territorial waters of Sri Lanka;

(c) any offence committed by any person in the air space of Sri Lanka;

(d) any offence committed by any person on the high seas where such offence is piracy by the law of nations;

(e) any offence wherever committed by any person on board or in relation to any ship or any aircraft of whatever category registered in Sri Lanka; or

(f) any offence wherever committed by any person, who is a citizen of Sri Lanka, in any place outside the territory of Sri Lanka or on board or in relation to any ship or aircraft of whatever category.

The High Court is empowered to pass life imprisonment and the death sentence for cases specified in law. In addition to the above list, the High Court also has jurisdiction over cases relating to maritime law.

Generally, a single Judge will determine cases in the High Court. However, an accused can choose to be tried by a jury where the case involves at least one of the offences specified in the Second Schedule to the Judicature Act (this includes murder, attempted murder, and rape). Under normal circumstances, an appeal against a decision of the High Court can be addressed to the Court of Appeal, and thereafter to the Supreme Court.

The High Court also has the power to subject controversial cases to a trial at bar. This would occasion the Chief Justice to appoint a special bench of three judges to determine the case in conjunction. A conviction passed by a trial at bar is considered more severe because anyone who wants to appeal against such a decision will have to address the Supreme Court directly. Bypassing the Court of Appeal, this would reduce the number of opportunities for the overturn of a conviction as well as narrow the chances of its success.

Certain High Courts function as High Courts of Civil Appeal, which have the power to hear appeals from the District Court. The purpose of establishing these courts is to lessen the burden on the higher appellate courts.

The Provincial High Court

J.R. Jayawardene and Rajiv Gandhi at a press event relating to the Indo-Lanka Accord. Established by the 13th Amendment, the Provincial High Courts were an indirect product of the Indo-Lanka Accord. Image credit: eyeofthecyclone.wordpress.com

J.R. Jayawardene and Rajiv Gandhi at a press event relating to the Indo-Lanka Accord. Established by the 13th Amendment, the Provincial High Courts were an indirect product of the Indo-Lanka Accord. Image credit: eyeofthecyclone.wordpress.com

These are special courts that were established by the 13th Amendment to the constitution. Other than the range of powers vested in an ordinary High Court, a Provincial High Court also has two additional roles: to hear appeals against decisions of lower courts, and to issue writs (more on this later).

In the former role, the Provincial High Court can entertain appeals from the Magistrate’s Courts, Labour Tribunals, and Primary Courts. Where these lower courts issue orders before reaching a conclusion, an aggrieved party can apply to the Provincial High Court to revise those orders. Furthermore, the Provincial High Court can hear appeals, as well as revise interim orders, made in cases under Sections five or nine of the Agrarian Services Act, No. 58 of 1979.

In the latter role, the Provincial High Court assumes some powers generally exercised by the Court of Appeal, by issuing a species of orders known as writs. These differ from a regular order formed at the conclusion of a trial after examining all evidence pertaining to a case. Their function is to question actions and omissions by the executive wing of the government and to order the executive to perform in a certain way. A party applying for a writ is called a petitioner, and there are six types of writs available:

- Habeas Corpus – an order to produce in court a person who is illegally detained

- Certiorary – an order for a lower court to produce a record of a legal proceedings

- Mandamus – an order for a lower court or a government officer to perform duties correctly

- Prohibition – an order for a lower court or a government official to stop performing certain illegal actions

- Procedendo – an order to redirect a case from a higher court to a lower court, asking such court to proceed to judgment

- Quo warranto – an order for an official to declare on what authority he or she is performing the action in question

The overlap of jurisdictions among the Provincial High Court and the superior courts is resolved in the following manner. Where applications for a writ regarding the same case have been filed to both the Court of Appeal and the Provincial High Court and the lower court has not yet initiated proceedings, the Court of Appeal may hear the application. Alternatively, the Court of Appeal may direct the Provincial High Court to hear the case. In the event a writ application concerns the violation of a Fundamental Right or a Language Right contained, respectively, in Chapter 3 and 4 of the Constitution, the matter will be referred to the Supreme Court for determination.

Any appeal against decisions of the Provincial High Court may be addressed to the Court of Appeal and thereafter to the Supreme Court.

The Commercial High Court

This court was added relatively recently by the High Court of the Provinces (Special Provisions) Act, No. 10. The Minister of Justice, in concurrence with the Chief Justice, can convert any High Court—that was established under the 13th Amendment to the constitution—into a Commercial High Court. However, at the time of writing, there is only one Commercial High Court, and that is in Colombo. It is given exclusive jurisdiction over the following cases:

- Commercial transactions where the amount of damages claimed exceeds Rs. 5 million. (However, if it’s the Defendant’s counter-claim that exceeds the threshold while the Plaintiff’s claim remains under it, the case will have to be filed in the District Court.)

- Cases that have been specified by the Companies Act No. 7 of 2007, such as the legality of a company’s formation, any cases of mismanagement, disputes among shareholders, and a company’s winding up.

- Cases coming under the Intellectual Property Act No. 36 of 2003.

The purpose of setting up this court was to provide speedy solutions to commercial disputes. It must be noted that cases filed under the Debt Recovery (Special Provisions) Act No. 2 of 1990 and land disputes are excluded from the jurisdiction of the Commercial High Court.

Court Of Appeal

The Supreme Courts Complex at Hulftsdorp, Colombo 12, which houses both the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court. image credit: UNAIDS

The Supreme Courts Complex at Hulftsdorp, Colombo 12, which houses both the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court. image credit: UNAIDS

The Court of Appeal is the first exclusively appellate Court, and is established by Chapter XV of the Constitution. It is made up of a minimum of six judges and a maximum of eleven—the leader of whom is called the President of the Court of Appeal. The powers of the Court of Appeal are as follows:

- Hearing appeals from lower courts to correct errors of law and fact

- Effecting restitutio in integrum, or reversing damages done by legal contracts to the original state, provided there are equitable grounds

- Issuing writs

- Punishing contempt of court

- Inspecting records of courts of first instance

Like the Provincial High Court, the appeal jurisdiction includes the power to revise interim orders given by lower courts. This power is exercised over the High Court and any other court below that.

Restitutio in integrum, or alternatively restitutio ad integrum, is a Latin term that means restoration to the original situation. This relief is available when parties harm themselves by entering into a lawful contract. According to Cooray, “under the Roman-Dutch law the grounds for restitution were fear, violence, fraud, minority, capitis diminutio, absence and justifiable error and such equitable grounds as justified the cancellation of the contract.” Most of those grounds are self-explanatory. Capitis diminutio occurs when a private contract diminishes a person’s legal capacity and freedom. The ground of minority can be used to cancel contracts when one of the parties involved is a minor (someone under the legal age of consent, which is 18 years). However, this is an exceptional remedy, provided for an applicant who has no other opportunity of legal relief.

Writ jurisdiction is the same as we encountered earlier, under Provincial High Courts. In addition to the above, Article 143 of the constitution empowers the Court of Appeal to issue injunctions to prevent “irremediable mischief” by actions ongoing or imminent. Furthermore, the Court of Appeal has the power to hear election petitions (Article 144) and inspect records of any court of first instance (Article 145).

The Supreme Court

The Supreme Court is the apex court of Sri Lanka. Its decision is final and open to no appeal. It consists of the Chief Justice, and not less than six and not more than ten other judges. Article 118 of the constitution sets out the roles of the Supreme Court as follows:

(a) Jurisdiction in respect of constitutional matters

Upon an application being made, the Supreme Court can determine whether or not a Bill proposed in parliament conforms to the constitution. In the case where the Bill is intended to amend or repeal the constitution, the Supreme Court’s role will be limited to determining whether the Bill needs to be passed by a referendum of the people. The President also may prefer any Bill he or she may think is urgent in the national interest to the Supreme Court for its constitutionality to be assessed.

The Supreme Court is also the only court that has the power to interpret provisions of the constitution.

(b) Jurisdiction for the protection of fundamental rights

The Supreme Court has the exclusive jurisdiction to determine whether the Fundamental Rights or the Language Rights of a citizen have been violated by executive action. Where such rights of a citizen have been violated, or feared to be imminently violated, an application can be made to the Supreme Court within one month for relief.

(c) Final appellate jurisdiction;

The Supreme Court is the ultimate receiver of all appeals. Prior to making an application for appeal to the Supreme Court, leave must be obtained from the Court of Appeal. However, in the event the Court of Appeal denies leave, the Supreme Court can still grant special leave for appeals to itself. In exercising its powers of appeal, the Supreme Court does not ordinarily re-evaluate matters of fact, but only determines matters of law. As Cooray states, the Supreme Court may interfere “in special circumstances… where the judgment of the lower Court shows the relevant evidence bearing on a fact has not been considered or irrelevant matters have been given undue importance or that the conclusion rests mainly on erroneous considerations or is not supported by sufficient evidence”.

When the Supreme Court does act in that manner, it would not reopen evidence, but rather examine whether the judge of the lower court has dealt with the evidence before him or her appropriately.

(d) Consultative jurisdiction

This is when the President refers any matter of law to the Supreme Court for its opinion, where the President thinks it is in the public interest to do so. According to Article 129, the opinion of the Supreme Court is formed by at least five judges sitting together. (The quorum of judges includes the Chief Justice, unless he or she decides to refrain from doing so.)

(e) Jurisdiction in election petitions

The Supreme Court has exclusive jurisdiction to hear petitions relating to the Presidential election or the validity of a referendum. The determination shall be made by at least five judges sitting together (who shall include the Chief Justice unless he or she decides otherwise).

(f) Jurisdiction in respect of any breach of the privileges of Parliament

According to Article 131, the Supreme Court may look into breaches of parliamentary privileges and punish such offenders.

Labour Tribunals And Quasi-judicial Tribunals

A still from the film A Few Good Men, depicting a scene from a Court Martial. Image credit: Universal Pictures

A still from the film A Few Good Men, depicting a scene from a Court Martial. Image credit: Universal Pictures

Although for the average citizen the Labour Tribunal is a popular meeting point with the law, it does not fall within the hierarchy of courts. The officer delivering orders in a Labour Tribunal is called a President and not a judge. The Labour Tribunal was set up by the Industrial Disputes Act exclusively to decide on disputes relating to employment. An employee could apply for relief such as compensation in case of wrongful termination, back wages, or even reinstatement at his or her previous office. To be eligible to apply to the Labour Tribunal, however, there should exist an employer-employee relationship between two parties, by virtue of a contract. A party aggrieved by the decision of the Labour Tribunal may appeal to the Provincial High Court.

There are other institutions for resolving disputes established by various laws, but which do not form a part of the conventional judicial hierarchy. For example, the Mediation Board is tasked with settling minor civil disputes that are of a value less that Rs. 250,000. Its existence is merely to lessen the burden on the judicial machinery. Parties who go before the Mediation Board can proceed to file legal action in court if they have obtained a certificate of non-settlement. Then there are other institutions such as Court Martials, Quazi Courts, and the Rent Board, which have been set up with highly specialised jurisdictions, and whose decisions are open to correction by appellate courts.

With this continuing series, Roar hopes to give the average citizen a closer look at the scaffolding and glue that keeps our government up. Await more articles that will better explain the complex of institutions, ideas, and histories that add up to what we call Sri Lanka’s democracy.