Prostitution is technically not legal in Sri Lanka, and so every once in a while, local newspapers will carry a news item that resembles the following:

“Police raid brothel in Battaramulla: The police raided a brothel that operated on Robert Gunawardena Mawatha in Battaramulla based on a court order. During the raid, the police arrested three women and a man who is believed to be the manager of the brothel. The police said that the suspects were arrested under the Vagrants Ordinance.”

Interestingly, news items like this are far more common in the days before and after Valentine’s Day. And when arrests are made during these ‘raids’, they are done so under the cover of one of Sri Lanka’s many leftovers from the colonial era — the Vagrants Ordinance, an archaic law which, to this day, calls to levy a fine of Rs. 5 on those charged with offences listed out under this..

But one doesn’t have to go as far as to operate a brothel to be arrested under the Vagrants Ordinance; depending on how law enforcers choose to interpret it, the simple acts of kissing or holding hands in public could land you in a lot of trouble under this piece of legislation.

What Is The Vagrants Ordinance?

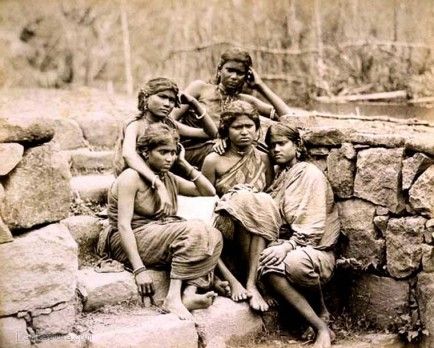

As most of us already know, when the British colonised Sri Lanka, they brought down workers from India to work in the tea estates. But because they were once independent people effectively reduced to serfdom, it did not take long for these plantation workers to attempt to run away.

As a result, the British administration drafted and implemented the Vagrants Ordinance in 1841, with the aim of apprehending the runaway workers and sending them back to the plantations.

The ordinance is one of the oldest laws in existence in Sri Lanka, and was drafted a mere 26 years after the British managed to lay claim to the whole island, following the second Kandyan War in 1815. The ordinance is even older than the words girlfriend and boyfriend, which are reported to have first appeared in writing only a decade and a half later.

Since its enactment in 1841, the Vagrants Ordinance has been subjected to 12 amendments, with the last being in 1978. However, its relevance as a law diminished a long time ago with the introduction of the Penal Code and other legal statutes, which form the basis of modern criminal law in Sri Lanka. Despite this, authorities in Sri Lanka still carry out arrests, especially of beggars and sex workers, under the cover of this ordinance.

Who Can Be Prosecuted?

The ordinance is recognised within the local legal community and international rights groups as being vaguely worded, which means the police can interpret it to arrest and produce in court a variety of people, who, by the same law, can only be fined Rs. 5-10, depending on how the case plays out.

According to Section 3 of the Vagrants Ordinance, any individual who does the following can be deemed an ‘idle and disorderly’ person, and police can arrest them without a warrant:

- Anyone (except priests and pilgrims who are performing their religious vows) who can look after themselves by work or other means, but willfully refuses to do so, and instead chooses to, or forces any of their family members to, be in a public space and beg or gather alms;

- A prostitute wandering in a public space and behaving in a riotous or indecent manner

- Anyone without any visible means of subsistence or of ‘bad repute’ who wanders into or stays in any verandah, outhouse, shed, unoccupied building, cart, vehicle, or other receptacles, without the permission of the owner;

- Anyone who defaces the side of any house or building or wall by fixing any placard or notice, or by putting up any indecent or insulting writing or drawing;

- Anyone who persistently and without lawful excuse follows, accosts, addresses by words or signs any person against their will and to their annoyance in a public space

Is The Vagrants Ordinance Still Relevant?

To this day, the Vagrants Ordinance is largely used to arrest beggars, sex workers, gropers, and, as it happens, young couples together in public.

Of the above mentioned categories, the ethics of arresting beggars and the debate on the legalisation of sex work are issues for another day. As for the third group of people — while it is fair to argue that those who harass others (especially women on public transport) deserve to be punished harshly, under the Vagrants Ordinance such people can only be fined a maximum of Rs. 5 and, upon being convicted, sentenced to a fine of Rs. 10 or a jail term of 14 days.

For comparison, even a bar of Chit Chat, once an infamous monetary alternative to Sri Lanka’s five- rupee coin, is now sold for ten rupees.

However, one of the most significant flaws with the ordinance is how it is used by the police to arrest young couples for something as mundane as holding hands in public. In 2010, the BBC reported how police in Kurunegala arrested 350 school-going teenagers for ‘indecent behaviour’ in public. Some months ago, police in Anuradhapura arrested 100 underage couples under the same charges. The problem here is that the term ‘indecent behaviour’, as it is employed in the Sri Lankan legal system, is vague and allows the police to interpret it in any way they wish to. It is under this pretext that the police take it upon themselves to arrest young, unmarried couples, who often tend to be teenagers still in school.

And their crime? Holding hands, or worse — kissing — in a public space.

When Holding Hands Is A Crime

Apart from the Vagrants Ordinance, the other law that is misused to harass or arrest teenage couples is Article 365A of the Penal Code. The article states: “Any person who, in public or private, commits […] any act of gross indecency with another person, shall be guilty of an offense, and shall be punished with imprisonment[…]”

However, as lawyer Aritha Wickramasinghe points out, showing romantic affection in public is not a crime, and no court in Sri Lanka has ever deemed it ‘grossly indecent’. In Wickramasinghe’s words, “The police are basically stretching their imagination and the ambit of the law to also include what is very normal behaviour. If the police think they can use this [law] to arrest couples holding hands and kissing in a public park, it also empowers them to go into people’s homes and arrest them for showing affection.”

The effect of such arrests is rather traumatic, especially considering the societal and cultural attitudes based on which underage relationships tend to be viewed in a negative light, particularly in rural Sri Lanka.

Even if police don’t go as far as to make arrests, they can use the threat of the same to harass and humiliate young people. A young girl had once told Wickramasinghe that a policeman had threatened to take her and her boyfriend to the police station when he found them talking together in a car. Fearing that her situation would be exposed to her parents, who did not know about her relationship, the girl knelt on the side of the road and begged the police officer not to take them to the station.

Even instances of two unmarried adults (above 18 years of age) landing in trouble for spending time together are not unheard of. This, again, can be blamed on the police exploiting the Vagrants Ordinance and applying it in a way that they are not supposed to. According to human rights lawyer Chandrapala Kumarage, there is no basis for this in law, and it is not a crime for a legal adult to spend time in public doing whatever they wish to do, as long as it doesn’t harm or inconvenience another.

With Minister of Justice Mohamed Ali Sabry recently stating his intention to reform the entire legal framework of Sri Lanka to suit modern times, it is imperative that relevant attention is paid to doing away with archaic laws such as the Vagrants Ordinance, which have even drawn criticism from Amnesty International and other human rights organisations over the years. There are, after all, more concerning behaviours that are far more deserving of action than two young people holding hands in public.