It is not uncommon to have bad days now and then, when all you want to do is curl up in a corner and nurse your woes. Occasional bad days are one of the inescapable hazards of living in today’s colossally messed up world. As Ernest Hemingway once said, “The world breaks everyone.” However, while most people recover fairly quickly and get back on their feet, some people stay broken for a long time. For these people, every day is a struggle to focus, stay upright, keep functioning, and maintain a semblance of normalcy. From the moment they wake up (if at all) to the moment they fall back into bed at the end of the day, they fight to keep their heads above the giant wave of negativity and despair that constantly threatens to overwhelm them. Needless to say, this is not something that can be simply written off as a passing phase.

This lasting manifestation of misery was recognised as an illness as early as, or even before the 4th century BC, and was first given the name “melancholia.” The ancient Greek physician, Hippocrates, described its characteristic symptoms as prolonged feelings of fear and despondency. Later, in the 19th century, German psychiatrist, Emil Kraepelin used the word “depression” to describe the condition. Contrary to uninformed, popular misconception, depression is not just a newfangled, imaginary illness concocted by psychologists to secure personal profit. It is an illness that is old as civilisation itself, and has been referred to throughout history by different names. Winston Churchill, who was haunted by manic depression for most of his life, famously called it his “black dog.”

Depression, its symptoms and types

Image source: tvscn.nhs.uk

Image source: tvscn.nhs.uk

Depression is a common mental illness, characterised by a period of overwhelming sadness, low mood, lack of energy, and loss of interest and pleasure. Other symptoms include constant fatigue, poor appetite, decline in concentration and memory, change in sleeping patterns, feelings of emptiness and worthlessness, unexplained physical pain, and recurring thoughts of death or suicide. It is often accompanied by symptoms of anxiety. Depression can change the way people think, feel, and act. It can impair an individual’s daily life, social relationships, and activities, causing a decline in their performance in school or at work.

The condition can be classified as mild, moderate, or severe, depending on the intensity of the symptoms. There are several variations of the illness that affect sufferers, all of which can become chronic if left untreated. The primary clinical forms of depression are major depressive disorder, dysthymia, and bipolar disorder. Other types include cyclothymic disorder, seasonal affective disorder (SAD), and postpartum depression.

People affected by major depressive disorder, also known as clinical depression, experience all or most of the aforementioned symptoms for a minimum of two weeks at a stretch, without an improvement in mood. Dysthymia is a less severe form of major depressive disorder, but the symptoms last for a much longer period of time. Bipolar disorder, which is also known as manic depressive disorder, manifests as alternating periods of low energy (depressive state) and high energy (manic state), with periods of normal mood in between. During periods of mania, sufferers can lose touch of reality, experience hallucinations and become delusional. Cyclothymic disorder is a milder version of bipolar disorder. Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) affects sufferers only during particular seasons, and is thought to be associated with the variation in light exposure in different seasons. Postpartum depression or post-natal depression is a type of clinical depression experienced by many women after childbirth. It can even be experienced, though less commonly, by men.

Another sub-classification of depression takes into account the cause for the condition. According to it, depression may be classified as reactive or endogenous. Reactive depression is believed to be triggered by a major change, stress, anxiety, or trauma in an individual’s life, and is, therefore, situational rather than genetic. Endogenous depression is assumed to have no discernible trigger, and is attributed instead to a genetic predisposition to the condition. This classification is considered obsolete by some, as it could be argued that in most cases, both situational and genetic components combine to contribute to the condition as a whole.

Then there is high functioning depression, in which the sufferers are able to effectively conceal their depressive symptoms. High functioning depressives appear to have fulfilling lives, and are able to participate in social groups, and in school or in the workplace, without giving away any sign of the mental agony that they are going through. They are able to maintain a positive public and professional façade, and do not fit the mould of the more well-known low functioning depressive, thus they are difficult to identify. These people tend to avoid seeking help for their depression, because the symptoms are not typical or obvious enough for them to establish a conclusion. Low functioning depressives, on the other hand, have a harder time hiding their symptoms and may not be able to function well in the society, school, or workplace.

Who is susceptible to depression?

Depression can occur at any age, but the symptoms may be difficult to spot in children and older adults. The indicators manifest in different ways in different people. There is no definitive cause for this illness, but it is believed that an individual’s genes, environment, and life experiences are all contributory factors. Depression can also be symptomatic of other more serious diseases, or it can even be the side effect of certain medications. People who have faced adverse or disruptive life events, or sustained some sort of psychological trauma in life, have a greater risk of developing depression, when compared to people without a genetic predisposition to the illness, who have not experienced trauma.

If left untreated, depression can lead to substance abuse, and suicide. Image source: prezi.com

If left untreated, depression can lead to substance abuse, and suicide. Image source: prezi.com

It is important that individuals with continued symptoms of depression consult a doctor or a mental health professional. Prolonged, untreated depression can lead to alcohol and/or drug dependence, other mental health disorders, deterioration of social relationships, withdrawal from the outside world, eating disorders, self-harm, and at worst, suicide.

Can it be cured?

Depression can be treated successfully, either with medication, self-help, or psychotherapy. Sometimes, a combination of all three may be used. The sooner the condition is treated, the more effective the treatment will be. Proper treatment can greatly enhance an individual’s quality of life. However, in many countries, only a small percentage of sufferers have access to effective mental healthcare. In several parts of the world, especially in developing countries, successful treatment of mental health illness is impaired by the lack of mental health professionals, shortage of resources, lack of awareness, and the fear of social stigma.

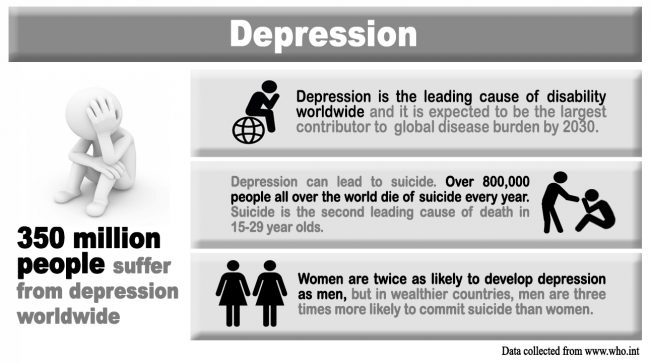

A look at the numbers

In April 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that approximately 350 million people of all ages around the world were suffering from depression. The same report also stated that depression is one of the main causes of disability worldwide and contributes largely to the overall global burden of disease. Thus, it plays a crucial role in the productivity and economy of a country. If this is not enough for skeptics to take the condition seriously, the WHO report also revealed that around 800,000 people die every year due to depression-related suicide.

The impact of depression in Sri Lanka is just as worrying as it is globally. Though we lack extensive data and numbers regarding the illness, clinical experience has indicated that depression is a common phenomenon in Sri Lanka. A 2011 study on depression conducted in a teaching hospital in the Central Province showed that out of the 144 patients reviewed, 65.3% were females. This corresponds with data from the WHO, which shows that there is a higher prevalence of depression among women, than men. In addition, according to the World Federation for Mental Health, maternal depression is linked with poor growth in young children, especially in developing countries.

The same study also showed that while severely depressed patients were more likely to receive inpatient care, those with mild or moderate depression either received primary care or went undiagnosed entirely. Almost a third of the patients under review had attempted self-harm at some point, with self-poisoning being the most common form of self-inflicted injury. This finding tallies with data from the National Council for Mental Health, which states that in the recent years, self-poisoning has been one of the most common methods of suicide in the country.

Sri Lanka has one of the highest suicide rates in the world, with 29.2 deaths per 100,000 population. Most of these deaths have been directly or indirectly attributed, by some, to basic mental health illnesses like depression – both endogenous and reactive, as well as to the stigma associated with these illnesses. In fact, shame or “lajja” has been discovered to be one of the main causes of suicide.

The civil conflict has a lot to answer for, when it comes to the nation’s deteriorating mental health. A 2011 survey conducted in the northern areas of the country showed an increase in the prevalence of mental health disorders due to war and internal displacement. In this study, 22.2% of the participants were found to be suffering from depression, while 32.6% showed anxiety-related symptoms. A later study conducted in the Northern Province in 2013 revealed that out of the 12,841 participants reviewed, 17.8% were experiencing depression.

One of the problems Sri Lanka’s health sector faces is the lack of mental health resources in the country. Data collected by the WHO in 2014 showed that there was only one psychiatrist for every 278,000 people, working in the mental health sector in Sri Lanka. Similarly, there was only one psychologist for every 833,000 people. Currently, there is just one hospital for mental health services in the whole island. Moreover, there are only 60 mental health units in general hospitals per 100,000 population.

These numbers show that there is an alarming dearth of mental health professionals and facilities in the country, indicating that we are ill-equipped to cope with the rapidly rising rate of depression. This is not good news, especially when depression is expected to be the largest contributor to global disease burden by 2030. Owing to our less than stellar status on mental health care and the general public’s dismissal of depression as a legitimate illness, we may be serenely cruising, with our eyes wide shut, towards an economic and healthcare crisis that we never even thought to anticipate. And the only way we can avoid the problem is by recognising it as one, first.