In a pub in Nottingham on 2 April 2011, Sri Lanka was playing India in the final of the Cricket World Cup on three separate TV screens. Indian spectators outnumbered the Sri Lankans ten to one inside, crowded around pushed-together tables, very anxious and a little bit hostile. The Sri Lankans, few in number and too out of touch with cricket to know whether or not they had a chance, were joined at the next table by a raucous and tipsy group of white English men who chanted “Muh-lin-gah! Muh-lin-gah!” in their unyielding accents any time the bowler stepped up to the crease. They watched him, barely blinking, celebrating loudly when he bowled out both of India’s opening batsmen, sharing statistics from his career and their predictions as to his performance in the match during advertisements. The Indians glared, but the Englishmen did not notice — the Sri Lankan team, they said, was their ‘second’. Their adopted side lost that day but like the conclusion all the evidence in Nicholas Brookes’ An Island’s Eleven: The Story of Sri Lankan Cricket points towards, there is only one assurance in Sri Lankan cricket: that a fall will always precede a rise, and that a rise will inevitably lead to a fall.

For a book written by a white man about Sri Lanka, An Island’s Eleven thankfully avoids all the usual cliches — exotification of the island and its inhabitants via contrived descriptions of alleged Sri Lankanisms, caricatural portrayals of real-life Sri Lankans as stock characters for the familiarity and comfort of a Western audience, overfamiliarity with and assumptions of local culture, history and social mores based more on lazy stereotypes rather than sincere research and observation. Of those I have read, foreign writers — and even, on occasion, locals and diaspora writing for an international audience — tend to write about Sri Lanka and Sri Lankans as they assume they are, or as they assume their audiences want them to be. One of the greatest strengths of Brookes’ writing is its curiosity – the conviction that, although his research is clearly meticulous, his scope expansive, and his passion for the subject palpable, there is yet more to Sri Lankan cricket and culture.

The 500-page historical retelling begins in 1800s colonial Ceylon, where cricket is played exclusively by colonisers in the hill country, and later by Burghers, whose status as natives trumps their light skin and proximity to Europeanness, and who are the first recipients of a characteristic of the gentleman’s game that has endured well into the 21st century: racism. Because Sri Lankan cricket is intertwined with its history, growing nationalism and Sinhalisation in response to British imperialism and discrimination are reflected on the pitch, where upper-class Burgher elites are gradually outnumbered by Sinhalese players from the middle and working classes over many decades. As the capital of the sport shifts from the hill country to Colombo, which becomes the centre of an entirely different brand of racism post-independence, Brookes’ writing is diligently conscious of the intersections between cricket and race, cricket and class, and cricket and nationalism.

Sections of the book are dedicated to breaking down the school system — the structure via which most local cricketers progress to the national team — and Big Match culture, unique to Sri Lanka. These chapters are the most successful in conveying the beginnings of Sri Lankan cricket culture, which stretched outwards from within the halls of schools like Royal College and S. Thomas’, where the author briefly taught while researching and writing this book. Included also, equally importantly, are the stories of cricketers who did not abide by this system — Lasith Malinga, for example — and by doing so helped force Sri Lankan cricket out of its snobbishness, a colonial hangover within the sport that placed breeding and pedigree on the same level of importance as skill and potential.

While the chapters set in colonial Ceylon, and even in the early days of independent Sri Lanka can feel a bit slow — partly because those eras in local cricket are not particularly memorable, and because I was not alive for the events of the bulk of the book — the narrative really picks up around the time Sri Lankan cricketers abandon their pursuit of the English style of cricket and embrace an approach to the sport that is authentically their own: resourceful, innovative, unpretentious. Around the same time as the birth of this Sri Lankan brand of cricket, the country itself was crumbling. Increased violence in the north of the island and in the capital as a result of the civil war combined with political insurrections cemented cricket’s status as a much-needed escape.

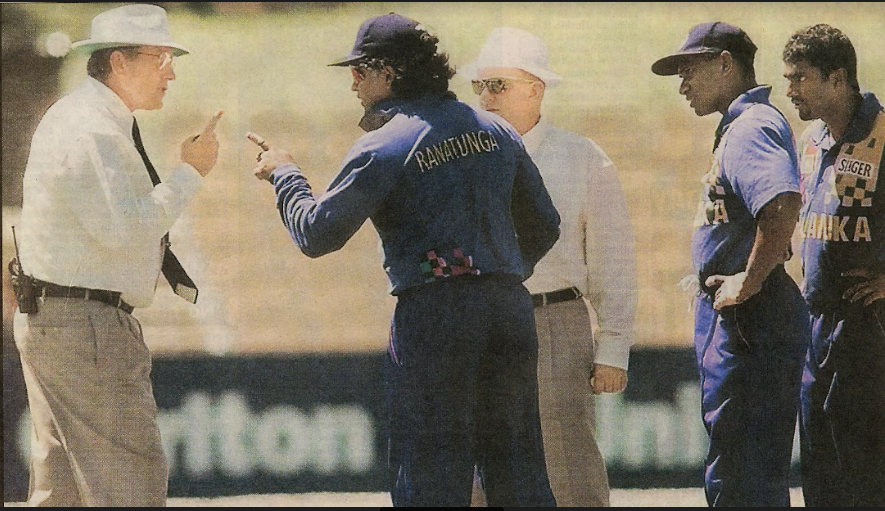

In the 1990s, a decade that has come to define Sri Lankan cricket, English colonial condescension is replaced by coarse Australian racism. An Island’s Eleven is a publicity nightmare for Australian cricket, describing in detail the sporting and cultural impact of the repeated indignities faced by the local team, and in particular Muttiah Muralidaran, in the country. It confirms the inevitable fate of a non-white nation playing a white man’s game: failure will be met with condescension, victory with vitriol, both of which will be rooted in the race of the players.

Brookes’ descriptions of critical matches in Sri Lankan cricketing history — Aravinda de Silva’s century during the 1995 Benson & Hedges Cup final, de Silva and Arjuna Ranatunga’s batting partnership at the 1996 World Cup final, Muralidaran’s 800th Test wicket in Galle in 2010 — will have you rushing to YouTube to see them unfold for yourself.

The writing is intentional and economical, and the commentary is detailed and quickly paced enough to make you feel as though you’re watching the match unfold in front of you at 10x speed. The personalities the narrative centres itself around are real and nuanced, but their larger-than-life presence in the sport is difficult to ignore. Brookes neither others nor oversimplifies them, but his thoroughness in documenting the full scope of their impact on the game may destroy some illusions. These men may have changed Sri Lankan cricket for better or for worse, but more often than not, for both.

Because Sri Lankan cricket culture is typical to this island, it was always bound to fall victim to other forces characteristic of it: politics, corruption, and greed. Brookes’ final few chapters are damning for Sri Lanka Cricket (SLC), and it becomes easy to understand how mismanagement, rank-pulling and manipulation have brought national cricket to where it stands now. It is a full-circle moment – as Brookes writes, Sri Lanka “once again find themselves regarded as a second-class cricket nation”. But as the 500-odd pages that precede this statement tell us, Sri Lankan cricket rises to its best when it has something to prove.

If the twists and turns of Sri Lankan cricket’s trajectory keep An Island’s Eleven exciting, the perpetual underdog complex the country’s cricket embodies makes it cinematic. The thoroughness of the research and scope enhances, rather than bogs down, subject matter that is inherently exciting. In the preface alone, as in the rest of the book, there are heroes and villains, redemption arcs, wrongdoing and revenge, humble beginnings, hard work, strokes of luck, reinvention, rags to riches, euphoria, and vindication. It would make a great movie.