The Wanathamulla area, situated in the heart of central Colombo, is considered one of the oldest low-income settlements in the major Colombo area. It has a vast, undocumented history. The first communities in Wanathamulla were built over mushy, wetland areas. These were followed by the first government-sponsored public housing projects, built on garbage dumps. From those early settlements to the modern day, Wanathamulla has had the unfortunate distinction of being an underserved community, rife with poverty, drugs and organised crime.

Like other underserved communities, one of the major issues plaguing Wanathamulla is the number of school dropouts. Despite the availability of basic facilities and infrastructure, children from Wanathamulla tend to discontinue mainstream education at some point of their childhood. Despite the presence of three major schools in the area, many of the children do not attend school.

Subsequently, they are left to find employment through other means – which often means peddling drugs or indulging in petty crimes. The reasons vary from finding occupation to provide an income for their families to falling in with the ‘wrong crowd’.

To find an enduring solution to these interconnected problems, the community has started its own Learning Centre.

Origins Of The Learning Centre

The Wanathamulla Community Learning Centre is the sole education centre in the area that is community empowered and crowd funded. It is sustained by volunteer teachers, lecturers and researchers that seek to impart the fundamentals of education to a community of children who are otherwise deprived of it.

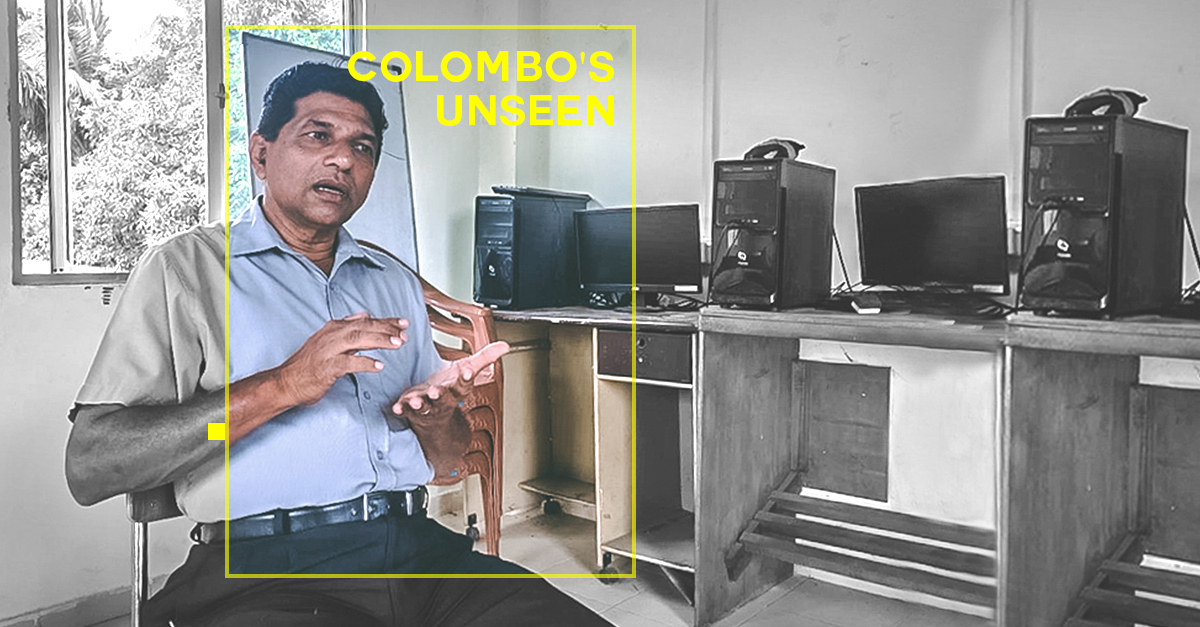

Kingsley Rajaratne is the founder of this institution. Having moved to Wanathamulla back in 2000, he has firsthand knowledge of what challenges the community faces.

While balancing his work at the Department of Posts, this frail and silent man in his fifties is passionate about changing the stereotypes the community has unwittingly adopted. An adamant believer in a ‘better Wanathamulla’, he has spearheaded a number of community initiatives. After being elected as a community leader at the Wanathamulla Community Union elections in 2011, Rajaratne constructed the Learning Centre in 2015, as a tool to empower children with education.

According to Rajaratne, the Learning Centre was built purely through a people’s process: that is, by mobilising the community and using the available talent, together with funds from the Sevanatha Urban Resource Centre and endowments received from the consolidated funds of the municipal council members. In other words, the Community Learning Centre was built by the neighbourhood itself.

“There are some children in this neighbourhood who drop out of school,” said Rajaratne. “They are barely supervised and are mostly neglected by their parents. These children get into drugs and the other vices that Wanathamulla is notorious for. The only way to overcome that is to give them a basic education, vocational training and proper recognition that would help them to find employment elsewhere.”

Honouring A Child’s Right To Education

Migara* is supposed to be in grade seven — that is, if he were attending school. But with both his parents being too busy to look after his educational wellbeing, Migara has been neglected. But with Rajaratne’s encouragement, Migara attends the classes at the Learning Centre, together with several other children from the area.

We first met him at Rajaratne’s home, when he came to announce that the children had tidied the classroom. He had run all the way there. Panting, the boy said, “Sir, madam. Good morning. ක්ලාස් එකට, එන්න.” (Come to the class)

A.B. Prelis and S. Prelis, an elderly couple who teach English to the group, smiled and greeted the child and jokingly said, “අපිට සිංහල බෑ. Say it in English.” (We can’t speak Sinhala. Say it in English) The boy shied away from a response. He looked down and smiled instead.

The Learning Centre has had two groups of children since its inception. They are taught English, Mathematics, mechanical work, sewing and the basics of Information Technology. On the Sunday we visited Wanathamulla, it was the beginning of the first class, and a new group had been just inducted at the beginning of the year. The group of eight children, all aged between 11 and 15, had gathered at the centre. The two teachers entered the room and the class was in session. Once the greetings died down, the day started with a song.

According to Rajaratne, the teachers and lecturers conduct classes every weekend on a voluntary basis. The retired teachers teach the children English and Mathematics, while a group of lecturers from the Moratuwa University teach Information Technology. The centre provides the children a certificate recognised by the National Institute of Education once they have completed the programme.

According to Rajaratne, he was motivated to start the learning centre because it is easier to change the mindset of children than that of adults.

“There are students who have dropped out of our programme,” he said. “I’m not saying it has been completely successful. However, there’s a clear difference we have managed to make in the children who took part in the course and even those who fell out. In the beginning, every weekend, we had to go talk to the parents and ask them to let their children attend classes. Now, it’s not so bad.”

Surviving Stereotypes

For the Prelis’, serving this neglected community has meant overcoming the stereotypes they had once held about it.

They candidly recounted how they lost their way during their first visit to Wanathamulla, and how glad they were when the person who took their mobile phone to get directions from Rajaratne, didn’t run away with it. “The environment was completely new to us, coming from Colombo 07,” said Prelis. “When our students learned that we were going to teach a group of children in Wanathamulla, they warned us not to. They were afraid for us. But after the first visit, we learned that we are needed here. We wanted to spend days just walking down these small roads, talking to people.”

The Prelis’ have a genuine interest in educating the children, to help them escape the harsh judgements of society at large. Despite their enthusiasm, however, their mission remains an uphill one.

“No one is there to actively push [the children] to pursue a formal education,” said the couple. “Attendance has always been irregular; children tend to drop out because they don’t get attention at home. They are not motivated enough to join these classes. Children who join prestigious schools have ambitions of one day becoming doctors or engineers. Not here, though.”