As we drifted into the second half of 2017 on the tail end of the monsoon, secondary school students all over Sri Lanka were propelled into a different kind of whirlwind—one involving back-to-back tuition classes and frantic preparations for the most important exams of their school lives. Application deadlines for GCE Ordinary and Advanced level (O/L and A/L) exams were wrapped up in June, taking away the peace of mind of nearly every Year 11 and 13 student in the country. Along with it disappeared the relaxed attitudes towards homework and lessons that prevailed during the beginning of the school year, and were replaced instead by a sudden flurry of academic application. A/L exams came to a close in early September, releasing older students from months of tension. However, the O/Ls still loom large in the horizon for Year 11s.

Sixteen year old Suresh*, however, is taking it easy. A Year 11 student in the government system, he ought to be sitting his O/L exams this December. But having intentionally failed to meet the deadline for the application, Suresh has no interest in doing his O/L exams or completing his education, despite his parents’ reproof. He is not otherwise occupied, choosing instead to seek part-time employment and idling away the remainder of his time. Another young school dropout, Fazila*, 16, has no hope of completing her education despite scoring well on her O/L exams last year, owing to her parents’ demand that she stay at home and help with domestic duties.

In Sri Lanka, education is compulsory for every child from the age of 5 to 16. worldbank.org

School Attendance In Sri Lanka

Though Sri Lanka has an above average literacy rate of 92.63% as of 2016, there is still a fairly significant number of children who do not complete school. In Sri Lanka, education is compulsory for every child from the age of 5 to 16. However, according to the Child Activity Survey 2016, a report released by the Department of Census and Statistics in February this year, an estimated 452,661 children (9.9% of the total child population) between the ages of 5 and 17 were not attending school at the time of the survey. Of these, 51,249 children, a large proportion of them between the ages of 5 and 11, had reportedly never attended school in their lives. It is possible that the 2016 statistics may be an underestimate, as the survey did not take into account children living on the streets, in institutions or at workplaces.

The 2016 Child Activity Survey covered 25,000 housing units in 25 districts, including samples from urban, rural and estate sectors. The data collected showed that most of the children in the country were living in rural areas (77.7%), while 17% hailed from urban areas, and 5.3% resided in the estate sector. Consistent with population distribution, the study found that the largest percentage of children not attending school (78.9%) were living in rural areas, while a lower percentage (17%) of the young dropouts hailed from the urban sector and the least (4.1%) from the estate sector. Overall, the survey revealed that more boys than girls, between the ages of 5 and 17, did not go to school.

However, the report noted that there was an acceptable reason for many of the children not attending school. At the time of the survey, a large number of children between the ages of 15 and 17 (236,819) were waiting for their GCE O/L results. The final estimate of children not attending school was also influenced by the sizeable population of five year olds (30,753) who were considered too young to start school. Lack of interest in education was another prevalent reason for children not wanting to complete their education. In total, 77,730 children of all ages who did not go to school, said that they were not interested in pursuing an education. Nearly twice the number of boys held this opinion, compared to girls.

Other reasons for not attending school included chronic illness, disability, financial difficulties, domestic and economic activities, lack of a suitable school in the vicinity, and an unsafe school environment in which the student was previously bullied or abused by classmates or teachers.

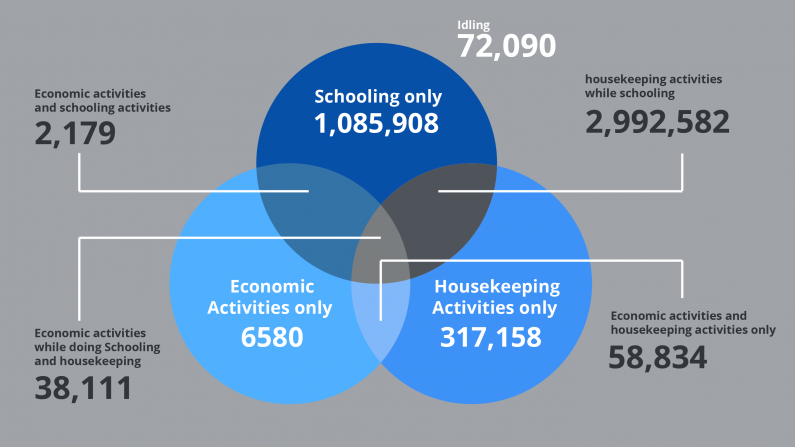

Venn diagram on activities engaged by children (5-17 aged) in srilanka -2016

The Link Between School Attendance And Child Labour

One of the most important things the survey revealed was the correlation between child labour and school attendance. Though it showed that 72,090 of the children not attending school were uninvolved in any sort of productive pursuit, a far greater portion of school-going children from 5-17 years (3,032,872) were juggling their education with economic activities and/or housekeeping activities. The report also indicated that more boys than girls were involved in economic employment, while more girls were involved in domestic duties within their own homes. Children as young as 5 to 11 years were shown to be engaging in agricultural labour, with most of the working children contributing to the family income by working in family-owned farms, industries and businesses. The study noted that 37% of the paid working children gave their earnings to their parents or guardians. The average income for child workers was found to be just over Rs. 11,000 a month, with boys earning a higher average salary than girls.

A significant number of children, both boys and girls (380,572), were unable to attend school because of their participation in economic and household work. The survey also highlighted that child labour is by no means abolished in Sri Lanka, with a staggering total of 103,704 children (2.3%) engaged in some kind of employment with economic value. The main cause of child labour was identified as poverty. The adverse effects of child employment mentioned in the report included failing health, injuries, poor performance in school, physical, emotional or sexual abuse, no time for leisure or school, and/or fatigue.

Child Labour Laws In Sri Lanka

Except under particular circumstances, the employment of children is against human rights and international law. According to the Minimum Age Convention (No. 138) adopted by the International Labour Organization (ILO) in 1973 and ratified by Sri Lanka in February 2000, the minimum age for admission to regular work is 14-15 years, depending on the economy and available educational facilities or lack thereof. The convention also states that if the work is not likely to be harmful to health and does not interfere with schooling or educational pursuits, children as young as 12 years can participate in it. However, the minimum age for hazardous occupation is 18 years of age.

The ILO further declares in the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999 (No. 182), that it is against the law for any child under the age of 18 to take part in or be coerced into a sub-sector of employment classed as “the worst forms of child labour.” This includes slavery, debt bondage, serfdom, compulsory or forced labour, recruitment of children for use in armed conflict, child prostitution, pornography, the use of children in illegal activities such as drug trafficking and peddling, as well as other work that is harmful to the health, development, safety or morals of the child.

Sri Lanka’s Roadmap on the Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labour, issued in 2003 by the Ministry of Labour Relations and Productivity Promotion Government, identified that the worst forms of child labour prevalent in the country at the time included commercial sexual exploitation of children, child pornography, trafficking of children from poor or conflict areas for domestic labour and illicit activities, and employment of children in begging, street vending, quarrying, mining, fishing, and construction work, among others.

Current Status Of Education And Child Labour

The 2003 Roadmap was developed with the view of completely eradicating the worst forms of child labour in Sri Lanka by 2016. However, the Child Activity Survey 2016 shows that an estimated 0.9% of the total population of children are still involved in hazardous employment, which include many of the activities described as the worst forms of child labour. While this number is low compared to child labour statistics in other developing countries, it remains a cause for concern.

Fortunately, the survey also shows that child labour is a decreasing trend in Sri Lanka. On the other hand, school attendance, which is a closely related phenomenon, does not seem to have followed the expected upwards trajectory, with data from 2009 showing that there were more children attending school in that year, compared to 2016’s estimate. This, coupled with the fact that child labour still exists, indicates that Sri Lanka has a lot more work to do in terms of universally enforcing the rights and protection of its children.

(*Names changed)

Cover image: http://groundviews.org