For Muslims around the world, the month of Ramadan means more than fasting from dawn till sunset. Visiting mosques and observing spiritual activities are key, while iftar, the meal at which the fast is broken, also makes Ramadan special.

While in some parts of Colombo restaurants break out fancy iftar menus, other areas witness an increase in the number of street food stalls come evening, and community iftar events have become increasingly popular, breaking down distinctions between class, race, and even religion.

We walked the streets of Colombo to capture some of the special ways in which people engage with Ramadan.

While most Muslims pray five times a day regardless of whether it’s Ramadan or not, mosques are filled with more people at prayer times during Ramadan than on a normal day.

A man recites the Quran at a mosque.

An elderly man on his way back home after completing his prayers at a mosque in Slave Island.

Kanji (porridge) is an integral part of the iftar meal for Sri Lankan Muslims. Almost all mosques make special arrangements to cook kanji in large quantities to distribute among the community. It isn’t unusual for people from different faiths walk in to grab some kanji and the doors are always open to anyone who wishes to do so.

A woman walks home after getting some kanji from the mosque and short-eats from the shop nearby, a common sight prior to iftar time.

Ramadan time means big demand for samosas. Vendors set up stalls offering home-made short-eats and other street food items to be bought in time for iftar.

A woman and her daughter wait for a vendor to pack up the food they have bought for iftar.

Samosas in the making.

It is no secret that Sri Lankans love their cricket. Quran classes at the mosque end early during Ramadan, which gives these boys more time to play the game that they love the most.

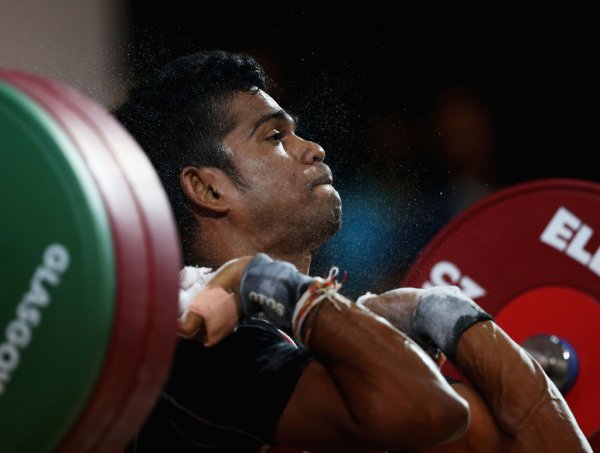

For those engaged in physical labour, work can get tough during the month of Ramadan.

Dates contain high levels of natural sugar and are considered great energy boosters, making them ideal to break the fast with. For Muslims, it is also a way of following the customs of the Prophet, who ate dates to break his fast.

It is a constant battle to get the best samosas of Colombo.

A vendor outside the Red Mosque in Pettah sells caps, perfumes, and mehendi (henna), which many Muslim women use to decorate their hands prior to Eid, the festival that marks the end of Ramadan.

Apart from short-eats, curd and treacle also sometimes make it to the iftar wish-list.

Faluda—another Ramadan favourite.

As the month draws to a close, Eid shopping is in full swing in Pettah.

Men, women, children, and elders all flock to buy new clothes and footwear for Eid.

In Pettah, some businesses close before sunset so the owners can head home to have iftar with their families; but not everyone has that luxury. As the call to prayer is heard, a group of people who do business in Pettah get together to break fast with some dates, water, short-eats, and kanji.

Those who don’t close shop before iftar opt to have kanji at their workplace.

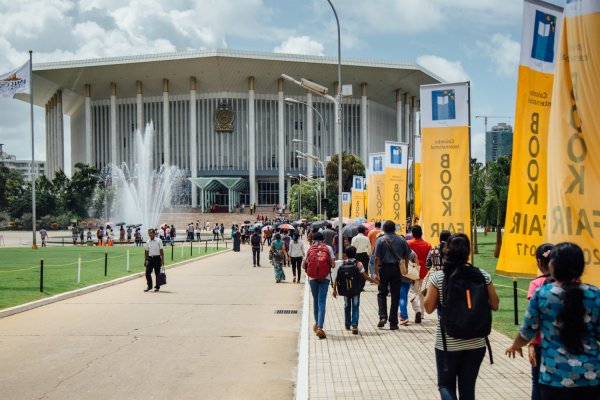

An interfaith community iftar is organised by the residents of Stuart Street in Slave Island. People living in the neighbourhood actively contribute to make arrangements for iftar.

People from all communities—including religious leaders—take part in the community iftar.

Iftar is often an exciting (much looked-forward to) time for children. While it’s not mandatory for children to fast, many of them try to fast when possible, as a means of training themselves to observe Ramadan when they grow older.

As the sun sets on Colombo, this street is filled with a seemingly never-ending line of people of different faiths, all sitting down together to share an iftar meal.