The Internet is an integral part of our lives. Most of us will be at a computer or mobile device, during the day, using the internet as our source of information. In fact, research shows that the younger you are, the more likely you are to forego conventional sources of information, such as books and tv, in favour of the internet.

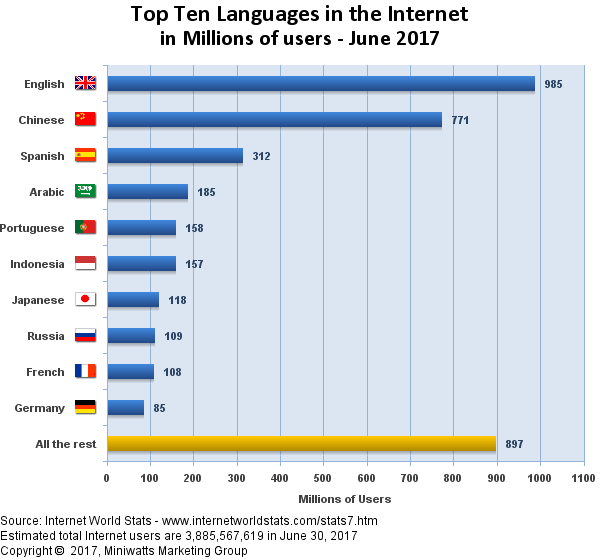

It’s also supposed to be a free and open source of information. With no gateways except the cost of the phone line, the information superhighway seems limitless. But is this really true if you don’t speak the de facto language of the web: English. While it appears to be a commonly held notion that buying a computer lab for a rural school will instantly turn them into genius students, the truth is that unless someone can bridge the language gap online, almost all information will remain inaccessible.

At one point in the 90s, it was estimated that 80% of the web was in English. While those numbers have changed quite a bit, if you don’t speak one of the major languages you will have a difficult time finding a use for most of the world wide web.

Does it matter?

A study showed that English only made up half the content on Twitter. 49% of tweets are in other languages, with Japanese, Spanish, Portuguese, and Indonesian showing the highest usage. Twitter users tend to interact with those who speak the same language, limiting communication to the same bubble. Even the nature of the language you speak changes the way you interact online. For example, you can say much more in Mandarin inside Twitter’s 280 character limit because of its pictorial nature.

The amount of information available in different languages directly affects representation online. Mark Graham of the Oxford Internet Institute said that “rich countries largely get to define themselves and poor countries largely get defined by others,” which skews the perception of any given situation. Research done by him and others show how much of the world is covered by a given language and that there is a stark contrast between languages like English, and languages like Egyptian Arabic, Swahili, and Hebrew.

What about Sri Lanka?

Kousalya from the Uduwila school, where the Schools Relief Initiative built an IT lab. Source:schoolsreliefinitiative.com

For some time, internet usage in Sri Lanka was limited to a relatively small user base of English speakers that had access to computers. It exploded considerably after the emergence of Sinhala and Tamil Unicode, which led to blogging in native languages.

For Sinhala speakers online, a notable group was The Sinhala Unicode Group. Malinthe Samarakoon of The Sinhala Unicode Group told Roar how dedicated the community was to getting unicode support for Sinhala. It was a collection of technology enthusiasts, developers, and font designers. In a time where Sinhala support was very limited, groups like these disseminated the necessary information. “We used to discuss reading issues on different browsers, [and] workarounds. I remember getting Sinhala up on iPhones those days. It was a revelation,” Samarakoon said.

He further stated how the Sinhala bloggers group stemmed from the Unicode group at some point. Samarakoon said, “people were very interested in creating blogs. I remember that very well. The group also helped everyone. From technical issues to getting Sinhala set up. We held a few blogging marathons to get people writing. I remember walking around in Kandy with group members distributing leaflets about the blogging marathon.”

Sri Lanka, today.

Student at Loyola Campus, Vavuniya. Source: jrsusa.org

Today the Sri Lankan web is more about local language content than English, with an almost immeasurable amount of sites and blogs in Sinhala and Tamil. Not counting the number of people that have found easy outlets for their creativity through social media such as Facebook and Twitter.

Native language in social media really shines in times of crisis. During disasters like the recent flooding, community responses were said to be much better than any initial responses through official channels. Ordinary citizens reported areas in need, collected relief items, and organized drop-offs with aid workers and rescue workers, all through social media and online platforms.

Even major media organisations have a native language presence online, both in reporting and social engagement. The rise of the social media commentator is notable. Individuals with experience in specific fields who choose to share their knowledge and views over social media posts. This is especially prevalent in the political realm. As theorized by many quarters, recent elections in Sri Lanka were believed to have been significantly influenced by online discourse. Most of this is in Sri Lanka’s native languages.

However, there still are significant gaps in knowledge. While politics often take front and center easily, topics like science & technology, art & culture, and international affairs are covered very little in native languages.

Roar’s own Chamara Sumanapala is known for bringing online content that is mostly in English to a Sinhala audience through analytical articles in Sinhala. He said how certain content is completely missing online and even in traditional media. “There’s a lack of native language content in many subjects. Even certain traditional media resort to taking information from sites like Roar for broadcasting. But because they don’t understand what they’ve taken, they often misinform rather than inform,” he said.

But there are efforts to bring global knowledge to the local sphere. Initiatives like Sarvodaya Fusion are “bringing digital access, digital literacy, and digital benefits, to every person in Sri Lanka.” Sites like Roar Sinhala and Roar Tamil are focused on bringing global content to a local audience. Community driven sites like baiscopelk.com offer subtitles to movies and tv shows in other languages. Channels like Roar ටෙක්, Tech Track, Chanux Bro offer tech and science content in Sinhala.

So despite most of the web still being in English, Sri Lanka’s native language web bubble is starting to fill with rich content. And as quantity grows, we hope that quality will grow as well.

To learn about more issues like Languages and Power on the internet, come to the Global Voices Summit 2017, on December 2-3, at TRACE Expert City in Colombo. Meet innovative, inspiring digital activists and citizen media communities from all over the world as they explore the issues of the open Internet, digital storytelling, and online discourse.

Featured image courtesy projects-abroad.ca