As a young boy, Charith* was never interested in the things that were typically regarded as “masculine”. He didn’t understand the hype of cricket, and found himself drawn towards hobbies that were traditionally considered more feminine.

“I loved to sing. My voice was much higher back then, and my singing voice was closer to a soprano, so I sang songs mostly performed by women,” he told Roar Media. “My parents’ perception of it was quite different. They thought that this automatically meant I would grow up to be gay. I can’t fault them for thinking that, because they were not entirely wrong.”

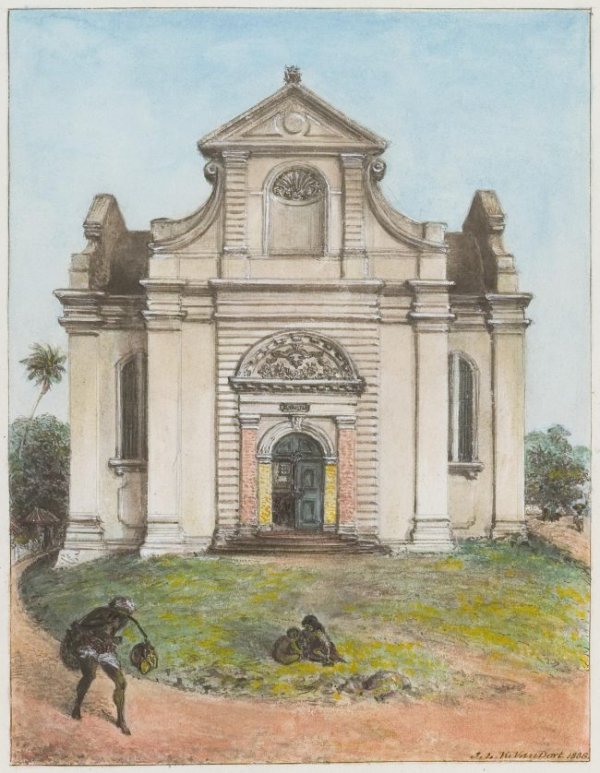

Charith identifies as bisexual, though he finds himself more attracted to men than women. Growing up in a devoted Catholic family, Charith’s sexual identity was something that his family felt needed to be ‘removed’ from him.

“At first, they tried doing little things in the hope of making me seem more ‘tough’. I wasn’t allowed to sing, and my father made me join the basketball and track team,” he said. “When I was a teenager, rumours began to spread about me and another boy, and so they took me to a psychologist who claimed to be able to ‘convert’ people like me.”

Conversion Therapy Begins At Home

Conversion therapy—or programmes designed to ‘convert’ people in the LGBTIQ spectrum— is widely practised in Sri Lanka, by both medical and religious institutions. Since homosexuality is illegal in the country, the practitioners of conversion therapy are allowed to operate freely and without question.

However, this does not negate the fact that such therapy can cause severe psychological —and in some cases, physical— harm to those who undergo it.

“There is no real scientific evidence which says conversion therapy works, and it has been proven time and time again to be unsafe,” said Nivendra Uduman, a counselling psychologist, who has been working in the field for over a decade. “Despite this, there are still practitioners who do it.”

For many of the children and young adults who fall within the LGBTIQ spectrum, conversion therapy begins at home.

“Many parents will take their child’s behaviour as an indication of being gay, and seek out advice from professionals on how to ‘undo’ it when their child is still young.”said Thushara Manoj, Senior Manager for advocacy at the Family Planning Association. “Usually, before they take their children for treatment, a parent will go to a therapist themselves. The first thing they’re advised to do is cut off their child from social media, from their phones, and to monitor their communications.”

According to Manoj, this is especially likely to happen to young boys who behave in an effeminate manner. In some cases, parents perceive their child’s homosexual ‘behaviours’ as externally influenced, and are told to cut off their child’s communication with the friends they believe are responsible. They are also advised to remove posters of anyone of the same sex that the child may have in his or her personal space, and replace them with posters of people of the opposite sex.

Even though these measures may be commonplace, they are not just baseless but also potentially harmful.

“When parents come to me saying things like: ‘My child is gay, would you be able to fix that’, I feel like I have a responsibility as a psychologist to explain to them that it cannot be fixed,” said Uduman. “When psychologists go along with the paranoia of these parents, and try to suggest all these pseudoscientific methods of conversion, it is irresponsible, and quite frankly, unethical.”

When these initial DIY methods of ‘converting’ a child fail — and they always do— that is when more extreme and harmful methods of conversion are used.

Pseudoscience In The Medical Field

Charith was made to visit a psychologist twice a week for two years, where several coercive and manipulative tactics were used to ‘convert’ him. He relates how, during one of the sessions, he was made to watch a video of heterosexual porn and asked to masturbate in front of his therapist. He becomes visibly disconcerted as he recalls this incident, and his otherwise steady, effusive voice begins to waver.

“I couldn’t really do it. I was quite young — about 17— at the time, and I felt so embarrassed, and extremely violated,” he said. “The experience was horrible, and afterwards I just felt guilty, as if I had failed. I am 44 years old now, and I still sometimes feel like I have failed.”

The methods used on Charith are among the many that are used by mental health professionals to ‘treat’ homosexuality. According to Uduman, many also try meditation therapy, and ‘guilt tripping’ as a means of trying to convert their patients.

“[These counsellors] will very openly say things like ‘How could you this to your god’ or ‘How are you going to face society.’ For them to say such things to a patient is malpractice,” said Uduman.

Many private hospitals also have psychiatrists who administer hypnotic and shock therapies on their patients to ‘counter’ homosexuality.

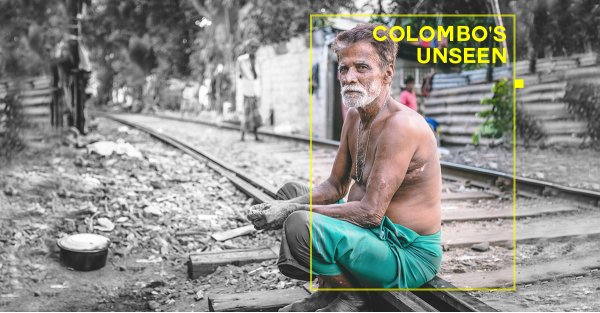

“There is a well-known hospital in Colombo, that has a [psychiatrist] who does electric shock therapy,” said Manoj. “This is done by showing a patient videos of homosexual porn, and then administering an electric shock. Then they will switch it to heterosexual porn, and play calm soothing music in the background. I have a friend who was put through this, and now he is unable to become aroused at all.”

These forms of malpractice are not solely relegated to the field of Western medicine. Many ayurvedic doctors offer their own forms of conversion therapy as well, and are often very open about providing it. Ads are often posted in the newspapers, with claims that they are able to ‘fix’ homosexual tendencies in children.

“There is a Sinhalese saying that bisexual or gay men’s genitals are small,” said Manju Hemal, Centre Manager for heart to heart, a collective that promotes sexual health and human rights for LGBTIQ youth. “The [ayurvedic] doctors will give patients an oil massage on their genitals to help ‘elongate’ it. The oil they use is called walas-thel (bear oil).”

But unlike ayurvedic doctors, private hospitals are more secretive about their services.

M.B. Adhil Suraj, an HIV activist, recalls that during his days as a pharmacist, people came in looking for silagra —or sildenafil— after having been advised by their doctors that it could cure them of their homosexuality.

Silagra is a drug that is used to treat erectile dysfunction and in some cases, pulmonary arterial hypertension. It has many side effects, including severe ones such as visual disturbances, bloody urine and heart palpitations.

Doctors that prescribe Silagra as a ‘cure’ for homosexuality, administer it to treat an illness that the patient does not have. By doing this, medical practitioners run the risk of inflicting serious physical damage on their patients.

“The existence of these ‘services’ allow abuse to happen in a very subtle way. They create a lot of guilt that will make patients feel ashamed of their own identity, and of their own bodies,” said Uduman. “This causes people to internalise homophobia, leading to things like depression and anxiety, and in some cases, even suicide.”

Policing Medical Practitioners

Although conversion therapy practices are not illegal in Sri Lanka, there is an overwhelming lack of scientific evidence supporting the idea that a person’s sexual orientation can be changed. For this reason, it is surprising that such practices continue to prevail in medical fields, largely without protest from other medical practitioners.

“There are so many unethical things that happen in the medical profession. In Sri Lanka, we do not have an ethics code for ourselves as psychologists. Doctors and psychiatrists will follow political ethics guidelines,” said Uduman.“There is nobody — either inside or outside the field— that you can go to, in order to call this practice into question.”

The prevailing cultural and religious stigma surrounding the LGBTIQ community in Sri Lanka is also deeply entrenched in the healthcare system of the country. This leads to a devastating lack of education on the part of medical professionals on how to care for their LGBTIQ patients in ways that are not mentally or physically harmful.

“It goes into the wider healthcare system. Nurses, midwives, all of these people don’t have a clue about how to work with LGBTIQ people because it is not taught. It is conveniently left out of the curriculum,” said Uduman. In the absence of standardised guidelines, Uduman believes that it is up to qualified medical professionals to effect change. “Change is not going to come from the law in this country, so it is up to us as practitioners to advocate for it. We need to advocate for change within the field, and make it known that the science does not stand behind these practices.”

(Editor’s note: In an earlier version of this article, a quote mistakenly mentioned that psychologists offer electroshock therapy. In fact, it is psychiatrists who are authorised to offer this form of treatment. The article has been amended to reflect this)