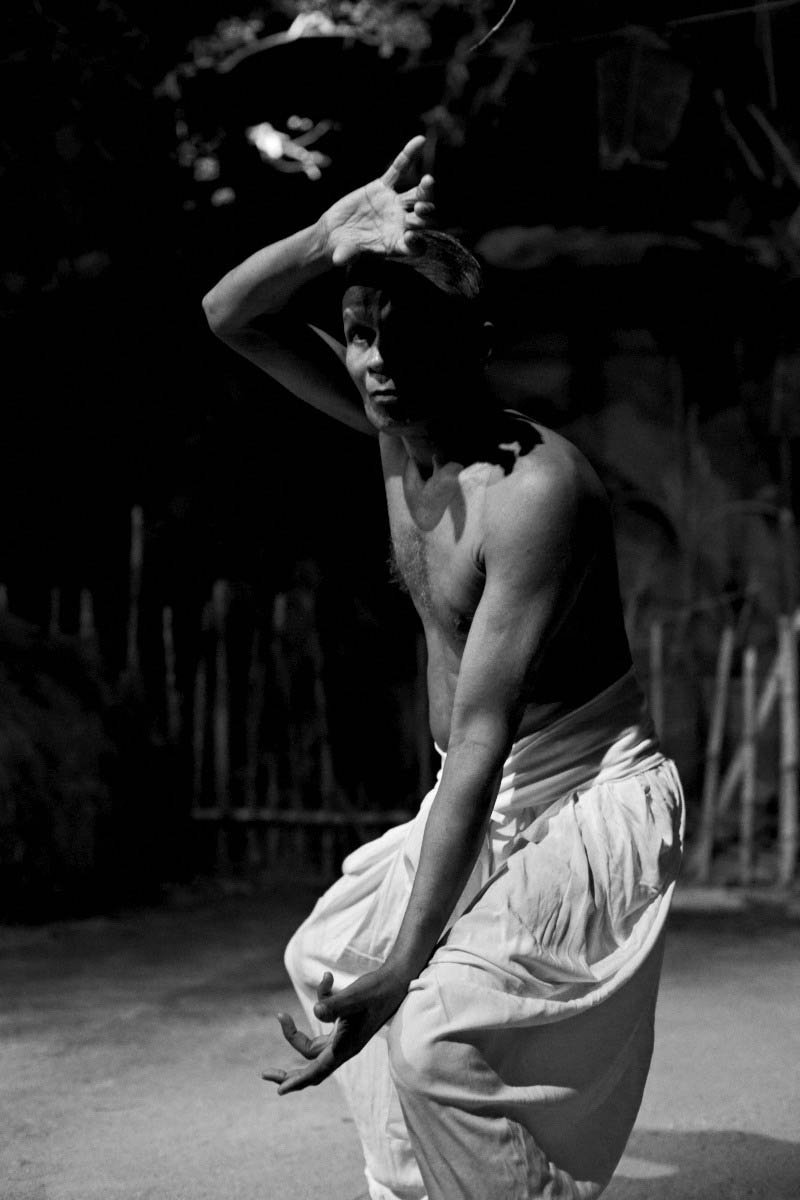

Her breath is slow and shallow, in and out. Her arms—fingers locked in an intricate gesture—are resting on her knees, with her legs crossed. She is meditating, focused on inhalation and exhalation. There’s a sword in front of her: its curved, black blade is slightly rusted, giving it a blood- soaked look.

She opens her eyes, ever so slowly.

She’s ready.

Despite its magnetic appeal, angampora, අංගම්පොර, has a missing link.

Its history is hazy, and is saturated with B-rate origin stories that try to market a myth. No one has been able to wrestle down the true origin of this martial art, which traces its roots to prehistoric war clans that inhabited Sri Lanka. Some research has suggested that it is over 5,000 years old and that it was practised by two main schools during the medieval period of Sri Lanka’s history.

On the other hand, historic texts claim that the art was practised by kings and princes, taught to them by village elders. Subsequently, British colonialists banned it because they thought it was being used for guerilla warfare.

The history is sketchy mainly due to the fact that the practice served as a familial bond for those who practised it. It was a legacy that was handed down from one generation to the other. Through word of mouth, and secrets that were closely guarded, the martial art has survived for more than two centuries.

On October 6, 1818, angampora was banned by English Governor Robert Brownrigg, following the Uwa Wellassa uprising. It was only last February, however, that the government took restorative steps and issued a gazette notification lifting the ban.

The decision came in the wake of a request made by the chief instructor of the angam unit of the Sri Lankan Airforce, Noel Ajantha Perera, to the Minister of Housing Development and Cultural Affairs, Sajith Premadasa. Subsequently, the Minister submitted a proposal to preserve and promote the practice of angampora and related forms and practices, which was approved by the Cabinet of Ministers on March 12 this year.

The proposal included steps to revoke the colonial ban on the practice of angampora and to declare it a national heritage. It further highlighted the need to allocate provisions to preserve and promote the martial art through events on a national level.

According to the Cultural Affairs Department, there have been several attempts to streamline angampora and bring it back into the public sphere. During the tenure of former Ministers of Cultural Affairs, T B Ekanayake and S B Nawinna, resources and finances were allocated to establish an angampora development centre in Mahawa in the North Central Province.

However, this plan never came to fruition.

With the current political interest in the practice, the Ministry officials are optimistic about its future, despite the lack of a master plan to ensure its continuation.

Untapped Potential

However, expert practitioners, masters and gurus maintain that the country is yet to tap into the greater possibilities of angampora.

Guru Piumal Edirisinghe, founder of the Sri Lankan Traditional Indigenous Martial Art Association (STIMA), is sceptical of the government initiative.

“There’s doubt among many of those who practice martial arts as a profession as to whether angampora can be taken seriously now,” he said. “Many of them have lost faith in the form because of the number of fraudulent practitioners that have saturated the market. Angampora is now seen as a joke and as entertainment by many of those who do sports.”

According to Edirisinghe, who is also the secretary of the National Angampora Federation, there are two possible avenues to develop what is possibly the world’s most secretive forms of martial arts.

“Angampora has to be developed in the country as a national sport,” he said. “We have examples from other countries we can follow. Kerala’s traditional martial art, kalaripayattu, which is very similar to angampora, has been developed and adopted into the modern context, sponsored by its government. Or take Muay Thai. Muay Thai is the sports version of the deadly classical art form called Muay Boran. Now it is a sporting event practised worldwide.”

According to Edirisinghe, angampora has the same potential. “It’s just that we do not have a common platform and national syllabus that is working with the intention of developing the martial arts into a more open and approachable sport,” he said.

Despite the lack of a concerted government plan, Edirisinghe believes that there are ways in which it can be revitalised.

“ The best way to do it is to make angampora a tourist attraction,” said Edirisinghe.

“Cultural activities such as the practise of angampora have a wide potential among tourists.” Whether or not this will save angampora is up for debate.