.jpg?w=1200)

Sri Lanka’s largest mangrove ecosystem is at threat due to the proposed construction of an aquaculture project.

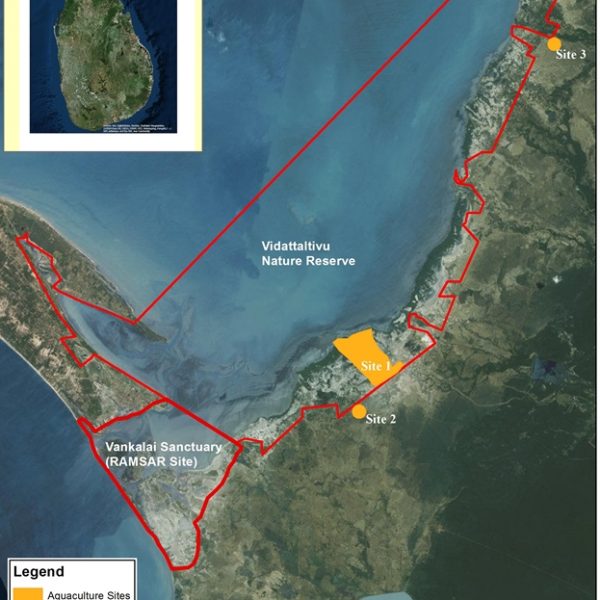

The Wedithalathivu (Vidattalativu) Nature Reserve, which comprises 29,180 hectares of land and sea, was declared a protected area under the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) in 2016.

However, a year later, the National Aquaculture Development Authority (NAQDA) put forward a proposal for the nature reserve to be degazetted in order to construct an aquaculture project: unleashing a tsunami of protests from environmentalists.

The Importance Of Wedithalathivu

According to Environmental Foundation Ltd. (EFL), Wedithalathivu—on the Mannar coastal line—is a rich and vibrant ecosystem consisting of mangroves, tidal or mudflats, salt marshes, seagrass beds and coral reefs, which support the livelihoods of fishermen in the area.

The mangrove system is unique because it is the only one in Sri Lanka in which the mangroves grow on the coast, facing the sea, providing a vital shield from cyclones, storm surges and tsunamis and playing a critical role in mitigating climate change.

The nature reserve was declared a protected area by an order made by the Minister of Wildlife and Sustainable Development Gamini Jayawickrama Perera, published in Gazette Extraordinary No. 1956/13 of March 01, 2016.

NAQDA’s Aquaculture Project

Aquaculture is the controlled process of cultivating aquatic organisms for commercial purposes, and NAQDA’s proposal, first put forward in 2017, was to construct a 1,000 hectare Aquaculture Industrial Park that will allow private entities to carry out various aquaculture projects, farming species such as marine finfish, crabs and exotic species of shrimp.

According to EFL, the project will encroach on three sites; one within the nature reserve, while the other two sites have been marked on the eastern boundary of the reserve.

According to NAQDA Chairperson Nuwan Prasantha Madawan Arachchi, the project was first proposed even before the natural reserve was declared a protected forest and the objective was to generate foreign currency to the country’s economy.

“There is an estimated USD one billion revenue from this project, and many countries such as Malaysia, China, Singapore and Japan have expressed their interest in purchasing our product. Especially the famous mud crab that can only be found in Sri Lankan waters,” he told The Morning.

Legal Framework

As per the provisions of the Flora and Fauna Protection Ordinance, altering a nature reserve can only be carried out after a proper study into the ecological consequences of the proposed change.

Following the proposal to degazette the nature reserve in 2017, the Cabinet ordered a full environmental impact assessment that was carried out by the National Aquatic Resources Research and Development Agency (NARA).

The NARA cleared 1,000 hectares as suitable for aquaculture, despite the proposal requesting 1,500 hectares.

However, environmental lawyer Jagath Gunawardana has emphasised that the assessment had clearly stated that further studies were needed and that in his opinion, the report did not support the project in any way.

‘Environmental Suicide’

At present, several environmental groups have begun lobbying against degazetting the nature reserve. Extinction Rebellion Sri Lanka and the Parrotfish Collective, both environmental movements and conservation communicators, have started an online campaign to spread awareness on this matter.

In a post, the Parrotfish Collective said, “Potential disease outbreak and seepage of chemicals from shrimp ponds causing water contamination, harming the fragile ecosystem consisting of corals and seagrasses are few of the possible negative outcomes of this project.”

The decision to go ahead with the aquaculture park, which many have lambasted as ‘environmental suicide’, is currently on halt, awaiting the degazetting.

However, if it gets the greenlight, many speculate that it will add to the bitter history of shrimp farms failing in the country, when, although large swaths of mangroves in the northwestern coast were cleared to farm shrimps for export in the 1980s, frequent outbreaks of disease led to about 90 percent of the farms being abandoned.

.jpg?w=600)