Editor’s note: Sri Lanka’s English literary circles have lost a great icon in the passing away of poet and writer, Anne Ranasinghe. In commemorating her life and works, Roar publishes below what is believed to be the last interview Ranasinghe gave prior to her demise this weekend. The interview has been published in its entirety, with the permission of the writer/interviewer, Devika Brendon. It is also due to be published (with added editorial commentary) in New Ceylon Writing, Volume 6, shortly.

Writer Anne Ranasinghe, who passed away on Saturday, December 17, 2016, at her home in Colombo, was born in Germany in 1925 and was the only survivor of her immediate family line, whose members were all killed in the Nazi death camps in WW2. She finished her education in England, married a Sri Lankan Professor of Medicine, Dr. Ranasinghe, and then lived in Sri Lanka for 67 years. She was one of the first poets to have her work published in the first edition of New Ceylon Writing in 1970, when she was then an unknown author, as she notes in the following interview. She has had a fruitful and productive literary life, publishing twenty volumes of poetry, and short stories, including And A Sun That Sucks The Earth To Dry, Plead Mercy, At What Dark Point, Who Can Guess The Moment? and Snow, culminating in her last collection, Four Things, published in 2016, in connection with the Cross of The Order Of Merit Of The Federal Republic of Germany, bestowed on her in 2015 by the German Government, in recognition of her lifetime of creative endeavour and achievement. Her poems At What Dark Point and Plead Mercy have been studied by students in the local English syllabus for several years. Anne Ranasinghe was the co-founder of The English Writers’ Co-operative (known familiarly as ‘the EWC’), many of whose members have been awarded prizes over the past two decades for their literary works. She was a committed and dedicated writer, who practised the art of creative writing until she perfected it, with a determination and a true love for literature which she speaks of directly in this interview.

“Working on a poem is one of the great privileges of life” – Anne Ranasinghe. Image courtesy colombogazette.com

In speaking of literature and life, I would like to begin, if I may, with your personal view of the nature of literature: in particular, your approach to poetry and story-telling, in both of which genres your achievement is a considerable one. Although it does not presume to teach ‘creative writing’, New Ceylon Writing welcomes the opportunity to hear about the experience of a practitioner such as yourself.

Literature deals essentially with the life of man, his reaction to his environment, and the forces and motives that shape human conduct. From the beginning of the First World War in 1914 to the end of the Second World War in 1945 more than seventy million people have died violently or have been exterminated. There is no way that we can ignore this fact, the enormity of it, or that it signifies a horrifying new dimension to the possibility of human evil. An awareness of the unpredictability of human conduct should perhaps infuse our writing with a sense of urgency to counter the possibility of ever-increasing darkness. Even here, on the other side of the world from Hitler’s Europe, we have had our own experiences to lend substance to these fears.

For me, it is not possible to concentrate entirely on poetry. Poetry is – how shall I put it? – the rare champagne. To write poetry there must be an experience so intensely felt as to exclude all other forms of writing: love or anger, fear or remembrance, and above all the perception of great beauty create a moment that wakens, or demands, a poem. There is then a period of gestation, a distillation of the experience, and out of this grows the first words of the poem. It is a momentary vision, a crystallisation which compels you to follow, sometimes through innumerable twists and turns, rarely straight on; for an hour, or two, or three – and sometimes over a period of months, even years. Right to the end of the poem.

Working on a poem is one of the great privileges of life, and I find it incredible that there are poets who believe a first draft is also a final draft, and must not be touched. That the first inspiration is holy. Either they are much better poets than I am or they are plain lazy and don’t like the tremendous effort that chiselling a poem into shape entails.

As for short stories, no one will deny that the first and foremost function of the short story is to tell a story for the sake of the story. Somerset Maugham caustically remarked that there are some among the intelligentsia who regard pure story-telling as a debased form of art, and he stipulates that extraneous knowledge and information should be used cautiously lest the story be swamped by the facts. Structurally a short story should have a beginning, a middle and an end; and, like a poem, it should have such concentration of mood and singlemindedness of purpose that no digression or deviation is permitted. There is a framework, and all action, all detail should serve to consolidate this framework, with no loose ends or spillage. Everything must add to the oneness and completeness of the story. It is this limitation that creates the very essence of it, distinguishing it from the novel.

The short story as we know it today is supposed to conform to certain principles, some of which I have just mentioned. Additionally, it should be of a certain length, and concern itself with but a single anecdote, episode or situation. The number of characters introduced should be limited. In actual fact, I doubt very much whether a writer planning a short story gives too much thought to these mechanics. There is a story to be told – and of course, ultimate success depends on the reader/audience, who have their own expectations: they want to be entertained or thrilled, shocked or made curious, or perhaps emotionally involved.

I write a short story out of a compulsion more or less similar to what makes me write a poem, but for me, a short story is much harder to write, and takes a great deal of time. I spend a great deal of time on polishing and re-polishing. In order to get started, I have to live my story for some time, I carry it around with me, and its full structure – beginning, middle and end – is more or less worked out in my head before I start writing. All my stories have as their core something that really happened, something that stirred me or upset me, or goaded me into comment, The problem is too large to be worked out in a poem; so I use the short story.

You have described yourself as “extraordinarily lucky”; and stated that although you “fell a number of times, you always landed on your feet”. These are optimistic statements, and express an extremely resilient attitude to life. How important is resilience in the living of life, especially of creative life? And how significant is optimism, as a quality that a creative writer should develop?

I didn’t actually say that, although I did ‘fall’ a number of times, and invariably ‘landed on my feet’. It was my ‘Mother-Aunt’ who made that statement! ‘Mother-Aunt’ in this context means ‘being in loco parentis’; as a thirteen-year-old, alone in England, I became her responsibility and her husband’s. After one week of getting ‘to know’ one another, I was speedily dispatched from their nice home in London to my school in Dorset. Naturally, there were many differences of opinion over a period of four years. I won my greatest victory when, after leaving school, my ‘Mother-Aunt’ apprenticed me as a ‘Junior Probationer’ at a beautiful home for blind babies for two years, to earn my living. My job consisted of potting the children after each meal. While I loved the kids and the place, at just seventeen I considered this a ‘waste of my time’. I began secretly to apply elsewhere, and landed a two-year training at the Moorfields Eye Hospital.¹

I had hoped to study medicine, and although I did very well in the Oxford Matric, I could not win a scholarship as I was still a German citizen. I had no money. My uncle, who was a Doctor of Chemistry, maintained that ‘in any case, women always get married’, and was not prepared to help.

This was 1942, and World War II was in full swing. Moorfields (at age seventeen or eighteen) was a great adventure. I was in London, and at the beginning of ‘growing up’ – in sometimes very dangerous situations. We were hit at the Hospital by a ‘Doodle Bug’: these were aeroplanes without pilots, controlled – we were informed by German soldiers at the French border. When they stopped the engine, or the machine ran out of fuel, the Doodle Bug dropped to the ground, causing a massive explosion.

You ask whether optimism is a quality a creative writer ‘should develop’. How? To become ‘optimistic’, you need opportunity. Sometimes you create your own opportunity, and then ‘fall on your feet’. Sometimes there is just no opportunity. The worst situation in which to be is when you have created an opportunity, and then somehow missed out on it.

Finally – creative writing may come partially from many things: talent, a particular home environment, encouragement, extensive reading, readiness to see the world from your own point of view, from some or all of these. But it is not just a gift: you have to work it out, and cherish it, and at all times to be faithful and convinced by your own thinking!

In response to an honour bestowed on you in 2015, the Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, you have said that you “will treasure it for what it signifies”. Since you have also said “I was born in Germany, was saved by England, and lived a very fulfilled adult life in Sri Lanka”, and have described yourself as “belonging to all three”, what does this award ‘signify’ to you?

With regard to the medal I was given by the President and people of Germany, my statement of acceptance was phrased in this manner: “I will treasure it for what it signifies and will continue to ponder my eligibility”. I am sure everyone who has read me over the years would fully understand the conflict.

But I regret the feelings involved by the many German contributors, and after ‘pondering’ the issue, I made my decision. It doesn’t mean the past is erased or forgotten: on the contrary, I live with it day by day. But I have found a means of compromising.

With regard to my statement that “I was born in Germany, was saved by England, and lived a very fulfilled adult life in Sri Lanka: I belong to all three”, that is very true. I was born in Germany, brought up in the seeming security of an established tradition of obedience, affection, reasonable independence, encouragement (especially to study), and exposure to all the available Arts till I was thirteen years old.

I have (somewhat ineptly) translated Federico Fellini, who has encapsulated my situation exactly:

Nobody may forget his roots,

They are the foundation for our whole life.

Where England is concerned: coming from the incredibly terrifying experiences of Germany, and although I was on my own, the atmosphere and daily life were unbelievably safe, the people friendly and helpful, the school fantastic. I spoke very little English, but was carefully taught by a group of devoted teachers. The freedom to use all the facilities available, the beautiful country open to visits without restriction, and the access to the Arts. Until the war curbed that way of living. But even during the worst days of the war, I was never made to feel an enemy, but joined in all defensive activities.

As for Sri Lanka: I have lived here now for sixty-seven years. I am sure I don’t need to explain that – although no one ever forgets that I am a ‘foreigner’ – I have been accepted, nurtured, and encouraged. I am deeply grateful to ‘belong’ as far as it is possible.

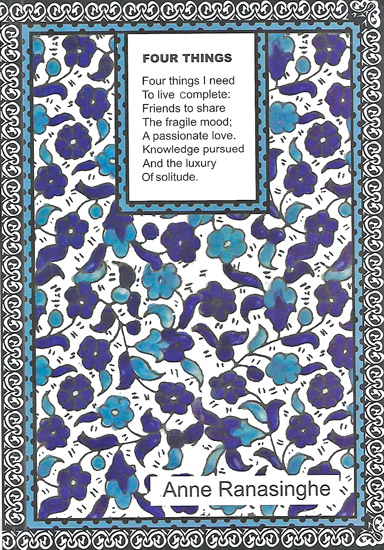

The cover of Four Things, Anne Ranasinghe’s last book. Image courtesy dailynews.lk

You have described this book of your selected works, Four Things, as ‘a rather unconventional book’. Could you please explain what you mean?

When Dr. Jürgen Morhard, Ambassador of the Federal Republic of Germany, first offered to sponsor a book of my selected poems, I was really delighted. My friends had been encouraging me, but I was reluctant – at my age – not having thought it through. But then, the temptation was too great, and I accepted.

However, when in January this year I had to start on it in order to complete the book before Dr Morhard had to leave Sri Lanka, I began to panic: I just hadn’t a clue what to use, how to choose, how big, and most important, to make it reader-attractive. Priyanthi, my printer, and I have no other help. Also, Dr. Morhard wanted a German section included.

I suddenly had an idea: a priest living not far from my father’s village, Hr. Pfr. Paul Gerhard Lehman, had earlier used my poetry for a small German journal, to write my family story. With his permission, I used his 60-page essay as my ‘Einleitung’ or Introduction. He talked to some journalists in the area – as a result, one of them sent me a set of photographs for a calendar, and I was allowed to choose a view from a balloon of my father’s village. A picture arrived of myself many years ago, and then I remembered all the translated poems – mine into German – and I realised I had enough material. I received some more beautiful and relevant pictures, divided the whole collection into relevant sections, and divided them by content.

Then I decided to use attractive book covers (of my 20) to separate them. It became more and more complicated. Having gathered by then 350-odd pages, I suddenly noticed there was no thought of a cover. Major problem. How to find a meaningful, attractive (and unique) design?

As I mentioned in Four Things, I was visited by a friend with his young daughter. She brought me a small gift – a ceramic dish with what I thought an unusual design. With some manipulation, it became a suitable back-cover. The girl is delighted – she is twelve years old! – and of course features in ‘the Acknowledgment’ page of the book.

When we had put together the whole ‘unconventional’ material, a letter arrived from a children’s school in Germany. We thought it so delightful that we added it to the very last page of the book, to leave a reader relaxed and charmed, as we were.

Your book positions the works in German as well as in English, and the format shows your ability to think and write poetically in both languages. Do you prefer one language to another when dealing with specific subjects?

This question really deals with the ability to translate, the art of translation. In 2002 I gave a talk at the British Council in Colombo, some parts of which may be appropriate to this subject. The title of the talk was ‘Moonlight stuffed with Straw’, a reference to an observation made by Heinrich Heine, the 19th-century German poet, that his own German poems, when translated into French, were like ‘moonlight stuffed with straw’. Vladimir Nabokov, nearer our own time, expressed his opinion in the poem On translating Eugene Onegin:²

What is translation? On a platter

A poet’s pale and glaring head,

A parrot’s shriek, a monkey’s chatter

And profanation of the dead.

There is, however, another approach, less traditional, which allows the focus to shift, at least partially, from the author to the translator and gives him/her a chance to be both daring and original. It shifts from strict literalism in translation to one that does experiment and tamper with usage to challenge and stretch language with the same vitality that the original possessed, and maybe create a greater vitality born of new linguistic and metaphorical contrasts. Especially in a multilingual context, translation can not only negotiate between languages, but could come to occupy literary space in its own right.³

Translation can be seen as a living spark between past and present, and between cultures. When you translate a poem you immerse yourself in another language, or at least you try to, and then you begin to realise the limitations of your native tongue – or maybe the tongue of your usage if you happen to have lost your mother tongue by living in exile or as a refugee, which of course has happened all too frequently in the course of the political upheavals of the last century.

But if you are really into translation, it is a very exciting adventure, and an enormously stimulating challenge. It strains your resources to the limit, making you aware of what you lack in facility and power of expression. Ultimately, it brings you face to face with the genius and structure of the original, and instills in you an urgent desire to do justice to it.

I have attempted translations from the German both of prose and poetry. One poem I have translated into English is Herbsttag, by Rainer Maria Rilke:

Herbsttag

Herr: es ist Zeit. Der Sommer was sehr groß.

Leg deinen Schatten auf die Sonnenuhren,

und auf den Fluren Laß die Winde los.

Befiehl den letzten Früchten voll zu sein;

gibe ihnen noch zwei südlichere Tage,

dränge sie zur Süße in den schweren Wein.

Wer jetzt kein Haus hat, baut sich keines mehr.

Wer jetzt allein ist, wird es lange bleiben

wird wachen, lesen, lange Briefe schreiben

und wird in den Alleen hin und her

unruhig wandem, wenn die Blätter treiben

Day In Autumn (Translation by Anne Ranasinghe)

Lord, it is time. The summer bore high yield.

Now cast your shadow on the sundial,

Release the winds across forest and field.

Command the last unripened grapes upon the vine

to swell, grant them of southern warmth a few more days,

urge them towards fulfillment, and then grace

with a sweet richness the heavy purple wine.

Whoever has no house now will not ever build.

Whoever is alone now will remain alone,

wake through the night, and write long letters filled

with sadness; and wander through the town

restlessly when autumn’s leaves are blown.

“Say what you will of its inadequacy,” wrote Goethe in 1827 to Carlyle. “Translation remains one of the most important and valuable concerns in world affairs.” And George Steiner added, “Without it we would live in a condition of silence.”

Dr. Jürgen Morhard [the German Ambassador to Sri Lanka] comments on your ability to ‘find a new home in words’. Could you speak to this concept?

I am not at all sure what he means by that; but it is true that once you become involved in writing a poem or a short story, you become part of it, in the sense that your surroundings disappear and you ‘live what you write’. I have also been told that the reader becomes absorbed as if he or she were participating – but I am sure that probably happens to other ‘creative’ writers.

In this context, however, I would like to refer to the poem “The Song has died from the Lips of the King” (in German, translated by Pfr. Paul Gerhard Lehman – page xliii – liii – Four Things – Introduction. In English page 60 – 63, Four Things.)

In November 1983 I returned to Essen and saw the remains of the beautiful Synagogue. Built in 1913, and considered the most magnificent in Germany, the whole interior was destroyed by fire in the “Reichskristallnacht”. The outer structure remained.

During the Hitler period Jews were totally isolated, and especially for us children the Synagogue became, before its destruction, the only place where we could meet and lead some kind of social life, exercise, study jointly, listen to music and so on.

So I decided to write a poem, reproducing in detail the beauty and significance of the Synagogue as far as I could, with the help of a book that my mother had sent earlier to England. It is a treasure, and I still have it.

Pfr. Paul Lehman has done a fantastic work in translating that poem, written in English, in his Introduction to Four Things (see pp. 60 – 63). But more than that: I have used 80-odd Biblical references which explain the original contents; and Pfr. Lehman has identified, numbered, and recorded each one in his German version. Unfortunately, I had no time to add this to the English version, but items can easily be identified.

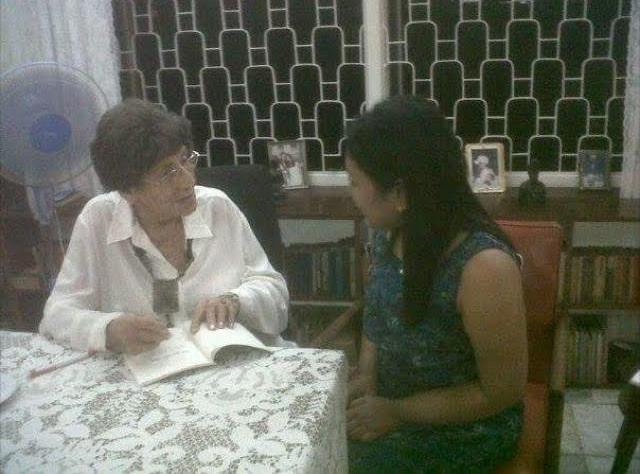

Anne Ranasinghe (left) at her home in Colombo. Image courtesy Daphne Charles (right).

Dr. Morhard commends you for ‘using your personal stories and the lessons learned from the past’, noting that you have ‘helped to reconcile the past with the present’, and that you have taught the younger generations that we should not allow a repeat of history’s great tragedies’. How and when did you realize the nature of the profound legacy your creative gifts could offer us? Could you also comment on the state of the world today, from your perspective? Do you think the role of creative writers and thinkers has become even more crucial than it was before?

When I asked some children in a school in Essen what they knew about Hitler, they were enthusiastic about the motorways he had built, and said that he had eliminated unemployment. Their fathers had told them that Germany was a better place under Hitler. When (during the making of a film about my writing) a Gallup poll questioned people in Essen at random as to what had happened to their erstwhile Jewish fellow citizens and taped their answers, some said they did not know. Others said the Jews had “gone away”, but they didn’t know where. And some laughed and said most of them had been gassed and went up in smoke. I have the tape. It is not an invented story. Even the laugh.

Since the reunification of East and West Germany there has been an upsurge of a vicious neo-Nazism and anti-Semitism that is more than reminiscent of the Hitler period, but covers a wider clientèle: apart from Jews, first the Turks and now all foreign and especially dark-skinned and dark-haired immigrants. I have mainly written ‘At What Dark Point’ for Sri Lanka, because readers here are still largely ignorant of the wider ramifications of the Nazi horror, and the bestialities that are possible. I think they should know. Knowledge is to some extent protection. In 2004, ‘At What Dark Point’ was translated into Sinhala.

George Steiner raised the question: How is it possible that the tortures and murders could be committed at Treblinka or Dachau at the same time as people in New York were making love or going to see a film? That problem is as relevant today for those of us who were not there (or are not there), but lived – or live – as on another planet. How can we teach the generations to come to feel deeply about those deaths that the world was powerless to prevent, or be alert to the deaths that can be prevented today, to which we can put an end?

In recent times, ‘elitism’ and ‘classism’ have been identified in the writing of those who are thought of as being ‘privileged’ in this society. Does a person’s socio-economic background have any impact, in your opinion, on his/her world-view, or affect their authority to speak to contemporary issues? Why is a person’s ‘status’ such an issue in the literary world, in contemporary Sri Lanka?

I hesitate to answer, as I myself have been identified, and indeed attacked, as being ‘privileged’ in this society. Actually, my past is such that I have not, nor will ever, ‘shake it off’. There is something contradictory in the fact that, on the one hand, you are not accepted as a ‘full’ member of this society (and correctly so); and, on the other, you are attacked publicly (by reviewers in the press, for instance) for being ‘privileged’. As a matter of fact, I resent this: I have been a hard-working woman all my life, and am surprised that I have managed to stretch my very limited means to support me for ninety-one years.

And yes, I do think a socio-economic background has an impact on one’s world-view; and certainly I feel no inhibition or lack of authority hampering my discussions of literary writing or contemporary issues. But I think I should explain that people who wish to express their ‘displeasure’ have seldom taken the trouble to study the item they are criticizing or reviewing: on the contrary, in their reading they have totally misunderstood what has been written. I have never had any objection to serious and constructive reviewing – quite the contrary. But I do feel resentment and injustice when I receive misrepresentation intended to destroy.

Dr. Lakshmi de Silva, translator and literary critic, has identified three categories in your poetry. Those who identify you as solely a ‘Holocaust Poet’ fail to recognise the diversity of your subject matter and your interests. Could you comment?

Lakshmi is, I believe, correct in her assessment. It is likely that some of the ‘Holocaust Poems’, which appeared not so long after World War II was over, overshadowed what followed. Professor Yasmine Gooneratne published my poem Auschwitz from Colombo in New Ceylon Writing in 1970 without knowing who I was, or how I came to be in Sri Lanka.

The fact is, that I had a busy and varied life, which changed dramatically after my husband’s death. My poems served as a kind of catharsis, arising out of powerful impressions, with no special objective. During a period of perhaps sixty-five years, they covered the events of a lifetime, and so I am not surprised that readers could not identify or ‘recognise the diversity of the subject matter’. I hope that my last book, Four Things, may help them to do so.

The poem ‘Amaryllis’ is one which fuses specific detail with intense symbolism and connotation, in a manner that opens it up to universal readers. How important has the rich, detailed experience of the sensory world been to you as a writer?

‘Amaryllis’ is a favourite poem of mine. I was sitting at my desk in my office, and watching this unbelievable happening: I wrote as it happened. The whole process was so smooth, so elegant and beautiful, I became totally involved and charmed. There was no question of choosing words or making corrections: this plant was as alive as I was, with its own incredible, distinctive personality.

And then, the tragedy

that the Amaryllis will bloom only once

because the soil and climate are alien.

How important has it been to you to find understanding in your readership? Has that need changed across your lifetime?

I am always delighted if my writing is found interesting or useful. But, basically, it is not important. I have to be satisfied, and that has not changed over the years.

What advice would you give to young writers in today’s Sri Lanka? Can you comment on how you think the literary culture in English can be improved, to foster Sri Lankan creativity in literature?

1. Parents should introduce children to books at an early age, reading to them and with them till they can do so on their own.

2. Visits to bookshops.

3. Membership of libraries.

4. Family discussions of ‘special books’.

5. I found the most valuable ‘reading years’ between being approximately seven or eight and the time I had to start working for a living i.e., seventeen or so. I have continued reading all my life, but of necessity, the working and domestic obligations limited me.

6. Schools should play a much greater part in stressing the life-long value of the reading habit. But as I am no longer in touch with them (my own children are now of ‘retiring age’), I may not do them justice.

7. Foreign languages are of great importance. My own parents insisted that I should join the Latin class among the boys. My friend and I were the only two girls to do so. I have never regretted learning Latin, and still remember sections after 80-odd years.

Notes:

¹ Anne Ranasinghe’s ‘Moorfield’, which isn’t on the internet, has been altered to ‘Moorfields’.

² Eugene Onegin is a novel in verse written by Alexander Pushkin that was published in serial form between 1825 and 1832. The first complete edition was published in 1833, and the currently accepted version is based on the 1837 publication. Its innovative rhyme scheme, its natural tone and diction, and its economical transparency of presentation all demonstrate the virtuosity which has been instrumental in proclaiming Pushkin as the undisputed master of Russian poetry.

³ A striking (and easily accessible) instance in Sri Lanka’s English literature of a verse translation that has, via scholarly and meticulous transliteration, ‘come to occupy literary space in its own right’ may be seen in George Keyt’s English verse translation of Sri Jayadeva’s 12th century masterpiece, Gita Govinda (Bombay 1940), which is based on Harold Peiris’s transliteration from the Sanskrit original.