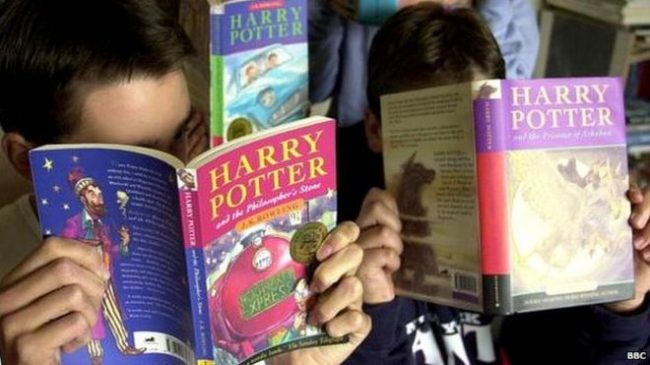

The latest installment of the story of The Boy Who Lived is now out, in bookstores of all kinds, simultaneously, throughout the world. In 2007, early in the morning on a cold winter’s day in the Southern Hemisphere, my friend and I stood in line to buy our pre-booked copies from the local bookstore, while normally stolid and respectable citizens of our suburb joined the queue dressed in cloaks and magical outfits, and a large man hired by the bookstore manager drove up and down the high street on a noisy motorbike with a sidecar.

We came home and started reading, from morning throughout the wintry day, updating each other as we went, on the big revelations. This was, after all, supposed to be the last tale in the saga. All the keys to all the mysteries lay therein.

I can hardly believe it was 9 years ago! And now the latest story is a play, and in London there is an outcry because the author has endorsed the casting of a black actor to play Hermione on the stage.

This is not how many readers of the books have envisioned her, apparently.

Noma Dumezweni, who plays Hermione Granger in Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. Image credit: Charlie Gray

Many people over the last 19 years have said that this story has encouraged children to read again. The adventures of Harry Potter and his friends and frenemies and arch-enemies have been a great vehicle for social commentary and political satire. Rowling has dealt with some big issues, in ways that children will never forget. Foremost among these are issues of social justice, equity and human rights.

The Mudblood/Pureblood debate, the movement to assert the supremacy of wizards over other magical creatures, the rising pro-marginalisation of minorities in the form of elves and giants and centaurs were all profound in their impact on the way children who read the stories in their formative years saw the implications of race hatred and bigotry. The bullying in the school room and the rivalries in the sports fields reflected the skewed stances of the grownups: the personal vendettas of Malfoy’s goons illustrated the race and class prejudices of the adult Death-Eaters. The divided wizarding world reflected the dangers in our own. And Rowling placed her faith in the children, to outgrow the hostilities of their damaged adult guides and mentors.

The poem she cited at the beginning of ‘Deathly Hallows’ highlighted her serious intent, and her awareness of what the contemporary younger generation are facing, which she portrays metaphorically, but which is real:

Oh, the torment bred in the race,

the grinding scream of death

and the stroke that hits the vein,

the haemorrhage none can stanch, the grief,

the curse that no man can bear.

But there is a cure in the house

and not outside it, no,

not from others but from them,

their bloody strife. We sing to you,

dark gods beneath the earth.

Now hear, you blissful powers underground –

answer the call, send help.

Bless the children, give them triumph now.

From Aeschylus, ‘The Libation Bearers‘

War, conflict, suffering, betrayal, loss of family, loss of home, threats to security, threats to personal safety, corrupt and indifferent governments, evil disguised as banality, exploitation and abuse of the innocent and the vulnerable… children all over the world see these at an earlier age than previous generations ever did. The books are in a real sense a course in Defence Against The Dark Arts. How to tell our friends from our enemies. How to find out what truly matters to us amidst all the chaos, and fight for its protection and its continuance.

Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, is a two-part West End stage play written by Jack Thorne based on an original new story by Thorne, J.K. Rowling and John Tiffany. Image credit: Rob Stothard/Getty Images

I loved the story, not because it was beautifully written, because there are some major patches of unevenness in the telling of the tale, but because of the irreverence of its postmodern anti-authoritarianism. Dolores Umbridge, evil in shades of pink and self-justifying sadism, thinly disguised by doilies and wallpaper awash with kittens, Cornelius Fudge, fearful enabler of Dementors, Mafalda Hopkirk, the lady who writes Harry all those scary letters on behalf of the Ministry of Magic, ruining his life and always ending by wishing him a nice day, the appalling Voldemort and the group of bullies, cowards and thugs who cohere around him, the flawed and eccentric father and mother substitutes, the recognisable English stock stereotypes (‘Anything from the trolley, dears?’), the privileged boarding school with its tower rooms and four poster beds, the dining hall with its loaded tables and sumptuous feasts, the individuated common rooms, the fantasy of being educated away from home, the eccentricities and the familiar traits of our school lives all woven into a medley of magic and postmodern myth-making.

It is a classic Hero’s Journey, with mentors, foes, confrontations with oracles, and soul-searing struggles in every sequence, brilliantly set against the counterpoint of an ordinary senior school progression from Year 7 to Year 12. There are some character sketches which are Hogarthian in their satiric brilliance, and Dickensian in their portrayal of moral depravity. And the humour at its best is joyful in its ironic exuberance.

I loved the strong messages of positive ethnic tolerance and colour blindness: that Harry’s first crush was Cho Chang, yet she is never overtly identified as Chinese. Two of the prettiest girls in the school are Padma Patil and her twin, with their dark plaits, but they are never identified as Indian. Ginny dates Dean Thomas, the irreverent Quidditch announcer Lee Jordan has rasta braids, one of the Quidditch team leaders, Angelina, is black, Kingsley with his rich, dark-toned voice is universally favoured, Ron’s werewolf-savaged elder brother falls in love with the fabulous French Fleur (‘I am good-looking enough for both of us!’) and Hermione is briefly romanced by the wonderful Bulgarian Viktor Krum, who has difficulty pronouncing her name. It is a veritable United Colours of Benetton, at Hogwarts!

The series introduces a number of characters of different racial origins – although the main characters seem never to be anything other than Anglo-Celtic. Image courtesy thereadingroom.com

But none of the main characters in the books or the films seemed to be anything other than Anglo-Celtic. And there never seemed to be curry night or yum cha or biriyani on the menu in the dining hall. It is wall to wall treacle tarts, ham and chicken pies, and Irish stew. Nothing even as exotic as a sun-dried tomato. It is a predominantly Anglo-centric story, and it seems as if it was always intended to be so. Rowling insisted that no non-British actors would be cast in the movies. It is the Englishness of the story, its similarities to the Chronicles of Narnia (except without the religion), to Enid Blyton’s Famous Five, the evocation of familiar tropes with slight tweaks and twists of whimsy that comfort and reassure the Anglophiles amongst us ‒ and within us. The ethnic and cultural diversity portrayed here is supremely managed. The non-Anglo-Celtic characters, (with the notable exception of Kingsley Shacklebolt, who becomes an important progressive figure in the latter part of the stories), are all in minority roles, not central to the narrative, and their being praised for their exotic qualities of voice or their beautiful smiles disturbingly suggests tokenism, which we absorb along with the other organising rules of the world Rowling creates.

Perhaps this tokenism is a reflection of real contemporary Britain, which, after centuries of colonisation fuelled by Anglo-centrism, may be developing the ability to look outside its own parameters and see equivalent centres of self in other countries and cultures as valuable and meaningful. Kingsley is the only adult ethnic minority figure represented who is praised for his political effectiveness and his leadership abilities. Even the Dursleys appreciate him ‒ by default! At school level, Angelina is very good at Quidditch. And everyone seems to interact as equals on a literally equal playing field.

Rowling’s wizarding world appeared to be a place where people were judged not on the colour of their skin but on the content of their character. So it is easy to see it as a moral and poetic saga: the end of each book sees our hero tussling ever more successfully with the inimical Dark Lord, and having a story-so-far summit meeting with Dumbledore, either in person or in his mind, where the take-home messages and mottos are underlined in Socratic dialogue, mentor to mentee. Its structure is reassuringly formulaic.

Dementors: one of the finest portraits of the struggle with depression seen in contemporary literature. Image courtesy harrypotterwikia.com

The sequence with the Dementors is one of the finest portraits of the struggle with depression seen in contemporary literature, and the protection against them, which must be learned, is a resonant one. Think of what makes you happy. Focus on that. It is your defence against the sadness which we all experience when we are at a low ebb. Lupin’s lessons are forms of cognitive reasoning therapy which can be understood by even young children. And I love that the remedy for a Dementor attack is chocolate.

The moral universe of the stories is drawn and shaped by a generous hand: it allows for us, along with the protagonists, to review and reassess our judgments of the characters we meet. The hard oppositional lines demarcating good and evil are blurred in this world ‒ we gain insights via magic into the circumstances which formed Voldemort and Snape, and Harry is confronted by unpleasant sides of his father which he must accept. We are shown the vulnerability and self-awareness of the great Albus Dumbledore, and the ‘superb’ courage of Minerva McGonagall. We see Harry’s unprejudiced openness to learning from the dispossessed: from the insights offered by the zany Luna Lovegood, from the bumbling loyalty of the huge and large-hearted Hagrid, and in his love for Dobby, the liberated self which transcends all barriers. In Hermione’s activism, we see compassion which eventually influences Ron and Harry to understand the plight of even the twisted house-elf Kreacher.

We see in Ron’s family’s poverty and Malfoy’s family’s scorn of it, and in the Malfoy family’s ill-treatment of others, their condescension and their competitiveness, how unpleasant and offensive a sense of entitlement based on inherited socio-economic status can be. Yet we see also the love and concern the Malfoys have for their son. My favourite moments are when the children rise above their histories and do their best to save each other, even from the Fiendfyre. That compassion and capacity for empathy under stress, to forgive in an instant, and deal with a complex reality as it is, changes the outcome for many people. There are echoes here of Frodo and Bilbo’s compassion for the pitiful Gollum in LOTR, and their ability to see what they have in common, even with someone who seems to be unambiguously against them.

Harry Potter created a revolution in reading for children the world over. Image courtesy bbc.co.uk

The kids who grew up reading Harry Potter must have all voted against Brexit: they surely voted to embrace difference and the life-enhancing opportunities it brings. It is such a pity that the older generation, with their memories of war and regional introversions and petty self-protective demarcations, outvoted them. Yet in some ways Ron’s insularity reflects an ignorance that Rowling presumably does not share, but which also represents a reality she is aware of. Neither he nor Harry even know what bouillabaisse is! We can excuse Harry, who (after all) was brought up in a small room under the stairs in Privet Drive, and Ron, whose family circumstances do not stretch to overseas travel ‒ even to France. But I personally welcome portrayals of an ever more diverse dining experience at the feasting tables of the world, both fictional and real. And I question whether a boy who finds bouillabaisse too much for him to handle at a meal would marry a black Hermione.

I am also dismayed to find that Rowling apparently married everyone in the core group of friends off to each other, and at such young ages ‒ did NONE of them do further study, except Neville? ‒ and how middle-aged, conservative, faded and weary they all looked as parents on Platform 9 and 3/4, seeing their kids off on the train to Hogwarts, to start another cycle. Did Rowling’s imagination fail, at that point? Will her spirited and original protagonists be limited by her own limits of experience, and her conception of them? They are only in their late 30s, at the end of Book 7!

Cast members of the play. Image courtesy: spinoff.comicbookresources.com

If Rowling can cast a black Hermione in the stage play, what else can she now do? Can a black Hermione separate from Ron on the grounds of intellectual boredom and boldly choose a different, less constrained life? Will she and Harry become entrepreneurs instead of merely working forever for The Ministry of Magic? Will some of their children go to Australia, not as an escape from bloodthirsty Death Eaters, but merely for a gap year?

I know in some ways that this outcome was the whole point. The best continuity hoped for by the citizens of this alternative universe would have been destroyed by the evil that was raging through their world, where the Dark Lord was trying to get at the kids from a young age and divide them into ideology-infused camps. Challenging that was what they had fought for in those epic struggles and battles of the will, and this was their prize: normalcy, ordinary family life, an existence which was not so intense, all the time. For people whose childhood was riven by war and trauma and dislocation, this was and is very heaven. We can surely relate to this.

But it may not be all that could be hoped for. It may be only the end of the beginning! The best may yet be still to come, for all of us, in that world, and in this.

Featured image courtesy standard.co.uk