Most of Sri Lanka’s ancient history, at least in terms of socio-political history, is gleaned from the Mahavamsa. Known as The Great Chronicle, this Pali epic is considered the ‘single most important work of Lankan origin’. Consisting of three parts written during three different periods of Sri Lankan history, the chronicles begin with the arrival of King Vijaya in 543BC and ends with when the British gained control in 1815.

The Sinhalese: From Inception To Colonialism

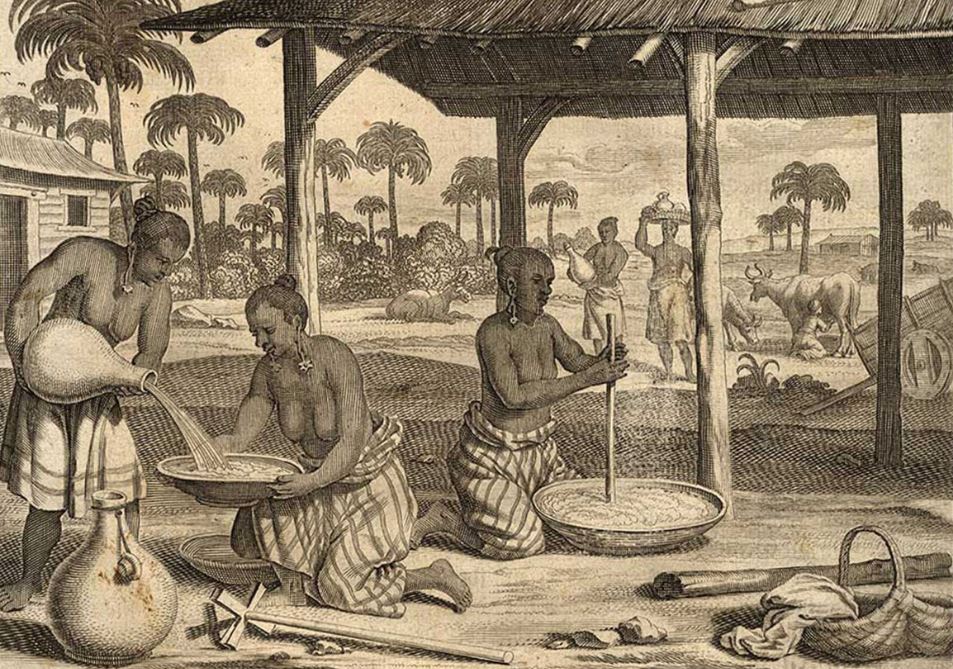

Image courtesy facebook.com/oldimagesofceylon

According to Professor Malini Endagama, one of the contributors to People of Sri Lanka, it is difficult to pinpoint when exactly the Sinhala community originated. Outlining the Chronicles, she points out that King Vijaya and his retinue of 700 were the first immigrants to Sri Lanka. Having embarked from India, Vijaya was the eldest son of Sinhabahu. Local folklore states that Sinhabahu was fathered by a lion, and had massive arms and strength akin to one (ergo the name, sinha meaning lion and bahu meaning hands). However, more realistic reports state that he was of a tribe which had a lion crest, which he was subsequently identified by.

It is widely believed that the Sinhala community as we know it are descendants of King Vijaya’s retinue, and of the indigenous tribes who were already in Sri Lanka at the time of their arrival. The tribes, known as the siv hela, were the Yaksha, Raksha, Naga, and Deva. Hence, the origins of the Sinhala people can be traced approximately back to the 6th century BC, and are a mix of Indian immigrants and local tribespeople.

However, organised religion and Sinhalese-Buddhism came to the country much later—during the 3rd century BC, when Arahath Mahinda Thero and Sangamitta Theri visited the country specifically to propagate Buddhism. The latter arrived shortly after Arahath Mahinda Thero, bringing with her a sapling from the sacred Bo tree from India, and professionals belonging to 18 guilds of arts and crafts. This resulted in an almost immediate expansion of art, architecture, education, and literature alongside Buddhist teachings.

The coexistence between the Sinhalese and Buddhism can be traced thus. Both continued to flourish as the principal people and religion in the country for centuries, even through numerous South Indian invasions which occurred intermittently during this period. What interrupted, and eventually ended, this long dynasty of self-rule in the island was the signing of the Kandyan Convention in 1815. This saw Sri Lanka’s last king being deposed, only to be replaced with British rule.

The Sri Lankan Tamils: Dating Back To The Nagas

Undated vintage photo of a young Tamil woman. Image courtesy imagesofceylon.com

Contrary to popular belief, Sri Lankan Tamils are not descendants of the country’s Chola invaders. According to the Mahawamsa, the invasions were targeted against Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa, both centres of dynastic powers. Professor S. Pathmanathan, in the book People of Ceylon, states that the Tamils from invading armies assimilated within those cities and were not considered as part of the original inhabitants, who were from the early Iron Age.

The Mahawamsa mentions four tribes of people who lived in Sri Lanka before the advent of Buddhism, the Naga being one of them. Studies by prominent archaeologists including S. Paranavithana and S.U. Deraniyagala suggest that the Naga could be identified with people from the early Iron Age, who arrived to the island from the Indian subcontinent. Their observations are based on studying approximately 9000 Brahmi inscriptions recorded on the dripledge of caves in Abhayagiriya, and on inscriptions found on burial urns.

Brahmi inscriptions and Buddha images in ancient temples also reveal that a large number of Nagas converted to Buddhism during the 3rd century, and that many Tamils in the Jaffna and Vanni areas were Buddhists. The inscriptions have been found in nearly all areas of the island, including in jungles, rock faces, settlement sites, temples, pottery, terracotta, sculptures, and coins belonging to the Naga community. They revealed that the Tamil-speaking Naga were a multi-religious community but developed relationships based on tribal links and kinship instead of language alone. Despite how widespread the Naga community was, it’s only Jaffna which was referred to as Naga-divaina or Nagadipa (‘Naga-land’). Manimekala, the ancient Buddhist-Tamil epic penned in the 2nd century, refers to the town as Nakanadu (nadu being the Tamil word for ‘land’).

The relationship between the Tamils and Sinhalese was political. It existed to help advance Buddhism and Hinduism, and to advance matters relating to the state. As such, intermarriages between Sinhalese and Tamil royal families were common, like King Vijayabahu I’s (1055-1110) sister’s marriage to a Pandyan prince.

Under the chiefdom of Nagas, Jaffna evolved into a kingdom around the late 13th century. It also became a port for trade with South India, and derived much of its wealth by controlling pearl fisheries in the Gulf of Mannar and trade across the Palk Strait. Fast forward several centuries, and the kingdom was eventually conquered by the Portuguese in 1619. This resulted in a rapid change of landscape as Christianity became the State religion. Thereafter, the Dutch seized power in 1658. While they made administrative, economic and judicial changes, they also codified the laws and customs of the Northern Tamils in 1707.

Traders From Across The Seas: From ‘Moor’ to ‘Muslim’

-

A large Moor family. Image courtesy asiffhussein.com

Not having nearly half as long a history as the Sinhalese or the Tamils, the Moors of Sri Lanka first arrived as Arab and Persian sea-traders, who sought textiles, spices, and gems from Southeast Asia. In the book People of Sri Lanka, Professor Dennis McGilvray states that the earliest evidence of Moors is limited to a few coins and tombstones. By the 14th century however, Adam’s Peak became a point of trans-oceanic pilgrimage based on an India-centric concept of Islam.

Sri Lankan Moors are a culmination of pre-colonial Arab and Persian sailors, and intermarriages between South Indian Muslims and Sri Lankans. Following subjugation during the Portuguese and Dutch eras (for both their faith and threat to the European monopoly on sea-trade), many Moorish traders settled in the island’s coastal areas moved inland towards Kandy.

Numerous political issues, from colonial subjugation to communal violence, lead to identity issues. As such, the Moors in Sri Lanka today have three possible ethnic identities: as ‘Tamil Moors’, ‘Arabs’, and ‘Muslim’.

The first was introduced in the early 20th century by Hindu Tamil leaders who attempted to categorize Tamil speaking Muslims as Muslim-Tamils, similar to Christian-Tamils. While Tamil speaking Muslims in Tamil Nadu embraced the Dravidian movement and identify themselves as members of the Tamil ethnic community, doing so in Sri Lanka is problematic as it would create divisions between the Sinhala-speaking majority and non-Sinhala speakers.

The second was to establish the Moors as an independent race akin to ‘Dravidian’ Tamils and ‘Aryan’ Sinhalese, and distance themselves from the ‘Tamil-Muslim’ claim. However, save for Islam, Sri Lankan Moors have almost nothing in common with Middle-eastern culture.

Eventually, the term ‘Muslim’ now denotes a Moor, despite the existence of other ethnicities—like the Malays and Bohras—of Muslim faith. According to the People of Sri Lanka, creating an identity based on a religious label provided a way out of language and race based conflicts which were erupting between the Sinhala and Tamil community. The idea of a ‘Muslim’ ethnicity caught off in the late 1940s, and the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress (SLMC) was created following violence by the LTTE against eastern provincial Moors in 1980.

The Sinhala community is still the largest majority by far, and constitute 74.9% of the population. The Sri Lankan Tamils are the second largest and now number 11.2%, with the third largest community being the Sri Lankan Moors who make up 9.3% of the population according to the 2012 census.

This wraps up our pieces about Sri Lankan ethnicities. The first two parts, documenting ethnic minorities, can be read here and here.

Cover Image courtesy slguardian.org/essays/ceylon-utopia