Shakespeare In The Park was a 6-day festival, held over three weekends in April and May, in which The Workshop Players put on evening performances of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Merchant Of Venice and Othello. These performances took place in the Open Air Theatre at Viharamahadevi Park in the centre of Colombo, and showcased some important aspects of our contemporary cultural life.

Admission was free, and audience enthusiasm was great, despite the threatening weather conditions. The stadium itself, a mini-amphitheatre, designed with descending tiers of stone converging onto an elevated performance space, enabled good vision of the stage. People started queuing about half an hour before the performances commenced, punctually at 7 p.m. Older people with walking sticks, kids running around, school groups, a medley, a myriad, of citizens.

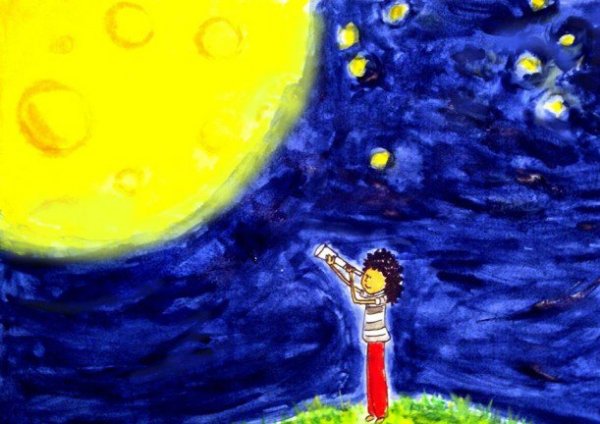

A scene from ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’. Image credit: Andre Perera/The Workshop Players

Shakespeare In The Park originated in New York, staged in Central Park, as an outdoor theatre festival which was intended to popularise theatre-going, making attendance at a dramatic performance accessible to all citizens of a city, irrespective of their social class and socio-economic status. It is a popular culture event, in contrast to the events held in theatres and concert halls and opera houses, and free of dress code. Cafe style food, drinks, and ice cream are sold, and it is arranged on a ‘first come first seated’ basis, a refreshing alternative to the hierarchical ticketing structures of almost every event these days.

At its heart, it is an interactive and collaborative event, not a display which can only be witnessed. Live theatre performances are rehearsed, but they are neither prescribed nor mechanical. There is room for improvisation, and the lines are not merely ‘by-hearted’ but delivered with brio and feeling. The actors wholeheartedly enjoy the characters they embody. High culture can often be seen by the general public as static, stylised, and intimidating. This, in contrast, is as colourful and inclusive and visually fluid as can be.

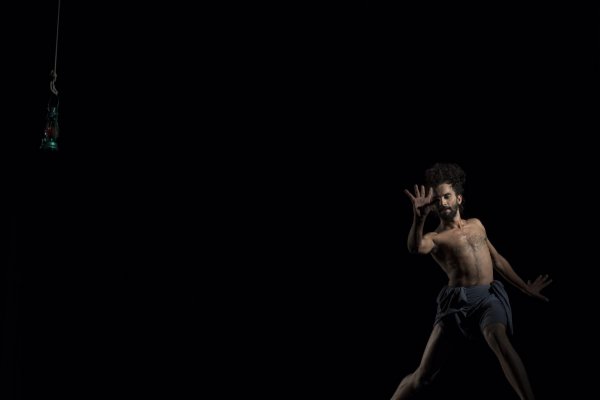

A captivated audience. Initiatives such as this one make theatre freely available to more audiences. Image credit Andre Perera/The Workshop Players

It is impossible to emphasise enough the significance of such an initiative in Colombo, at this particular point in Sri Lanka’s cultural history, when the country is opening up to the outside world after years of horror, trauma, and frustration, to which the understandable and survivalistic response has been endurance and introversion. Western food, art, music, and literature have been presented, in this Democratic Socialist Republic, as elite indulgences available only to a privileged few.

The opportunity to access available sources of global, rather than just local, culture is the mark of an open and free society. For the people of a city, of all generations and backgrounds, to have the ability to attend pure metal concerts, chamber music performances in cathedrals and churches, eat olives and smoked salmon and buy European style bread at the Good Market, eat locally made cheeses alongside Sri Lankan bites and not feel unpatriotic or elitist in their preferences, because all these products coexist, is surely a joyful outcome, after years of deprivation, scarcity, and suffering.

The goodwill and cheerfulness of the audience at this Festival matched the energy and enthusiasm of the actors, and virtually all attendees came with umbrellas and shawls to fend off the elements. This is the first Shakespeare In The Park festival to be held in Colombo, and it was a vibrant celebration of the popular elements of theatregoing which Shakespeare, who was an actor himself, would have certainly approved: the open-heartedness of the participants, the optimistic determination to proceed with all performances despite the rain, the gorgeous sensation of having falooda ice cream in the interval, the pleasure of seeing Shakespeare’s characters, both comic and tragic, colliding and colluding and conspiring on stage.

“The opportunity to access available sources of global, rather than just local, culture is the mark of an open and free society.” Image credit: Andre Perera/The Workshop Players

The lights in the trees, the sound of the winds blowing through the leaves above our heads, the beautiful, lilting Renaissance music which played as we climbed up the outside steps and entered the gates and descended into the amphitheatre and took our seats, the flashes of lightning, the outbreaks of thunder and the cathartic outbursts of rain all contributed to the sound and light effects of the sensory outdoor experience.

At the performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the audience fully appreciated the vivid characterisations of the characters by the young people: the athleticism and mimicry of young mister Robin Goodfellow, who at one point threw himself bodily into Oberon’s arms and imitated the action of a bow and arrow, the inspired use of leaf fronds to suggest the personified forest and the characters’ confused meanderings through it, and the heartburnings of the young ladies Hermia and Helena as they traversed the gamut from being friends to frenemies to being friends again, while sorting out their interpersonal issues of self-esteem and dignity and pride with interspersed words and fisticuffs.

This festival was held to celebrate Shakespeare in the 400th anniversary of his renown, and it was wonderful to experience his work in such an exuberant and appropriate way. This festival signals a great opportunity to celebrate the arts and humanities in public spaces in a city and a country in which these spaces have been contested for so many years: rendered dangerous to visit, by guerilla war and political incidents, occupied by ritualistic displays of public power and military might, and policed by regulatory governing bodies. In a society in which public parks and spaces are being opened up, after so many years of terror, apprehension and anxiety, it is appropriate and profoundly balancing that joyful incidents like this should now occur in them.

The winds were so strong at times during the opening sequence of The Merchant Of Venice that items of the stage set and scenery were blown down, and the rain was so fierce at times that the lively words between Portia and Nerissa as they laughed at Portia’s wannabe suitors could not clearly be heard, yet many people in the audience stayed right through to the end, and this could not just have been out of loyalty or a desire to support specific members of the cast or support team of The Workshop Players. To enable the facing of such a barrage of elements, there must be an abiding love of literature and drama itself, and an appreciation of the efforts of those seeking to embody characters whose portraits add much to our knowledge of our shared human condition.

Shakespeare in the park: the cast, undeterred by adverse weather conditions. Image credit: Andre Perera/The Workshop Players

The weather poetically mirrored the intensity of the performances! For A Midsummer Night’s Dream, a comedy with lighter conflicts and mitigating circumstances, the rain was light and intermittent. For A Merchant Of Venice, with its dark and intense vengeance theme centred on Shylock, an alienated and bitter individual, the skies darkened, and the rain was so heavy that temporary shelter was needed. Innovatively, inclusively, and imaginatively, the audience was invited onto the stage for the performance of Othello, where they could have an immersive theatrical experience without themselves being physically inundated by rain which was so heavy it fell not in veils but in blankets.

Humans are responsive creatures, absorbing and reflecting what is enacted around us. We respond and react to our ambient context, and unconsciously imbue the cues and prompts of our settings. Spaces of beauty, expressiveness and spontaneity are cordials for our souls. So often these days, our experiences are event-managed: regulated and controlled and cordoned off, in an effort to deliver to us a pre-paid and packaged experience. Along with that level of organisation, very unfortunately, often comes a loss of joy.

This did not occur in this space. Sorrow was displaced by joy!

Featured image credit: Andre Perera/The Workshop Players