Sri Lanka has a debt problem. Period.

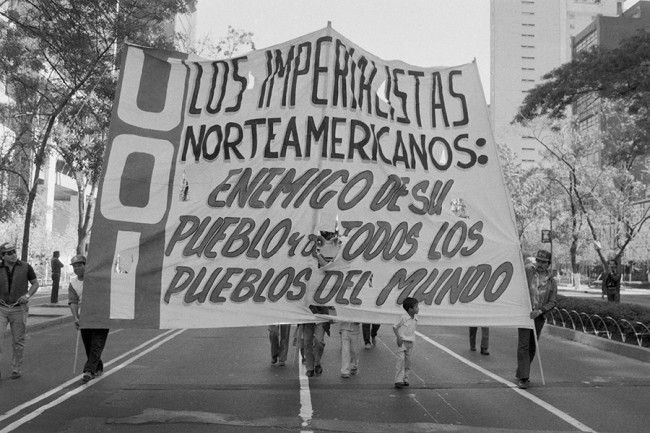

Don’t panic, it’s a far cry from the Latin American debt crisis. Yet, left untreated, Sri Lanka’s debt overhang can and will sink the economy. Excessive debt will also impinge on economic growth, bringing down everyone’s living standards. And make no mistake, the clock is definitely ticking.

With that in mind, this month’s op-ed aims to look at what’s behind Sri Lanka’s inability to manage its debt burden.

Protests during the LatAm debt crisis. Image Credit: Sergio Dorantes/Corbis

The root of the problem lies with the fiscal policies pursued by successive governments of the country. For the uninitiated, a country’s macroeconomic stability rests on the soundness of its fiscal and monetary policies. A country’s Central Bank is supposed to take care of the monetary policy, while the Government is supposed to handle fiscal policy. Much like a set of cogwheels, both policies need to mesh very well in order for the economy to grow.

But before we go any further, it pays to understand how, and why, a government’s fiscal policy forces it to borrow money. Here’s an easy way to understand the logic behind government borrowings:

Every year, the government presents a budget, which is simply the spending plan of the government for the coming year. The budget in turn, is financed by tax revenue. But tax revenue alone is usually inadequate to cover the entire budget, creating a mismatch between revenue and expenditure (i.e. expenditure > income). This mismatch is termed as a ‘budget deficit’, and in order to finance it, the government resorts to borrowing money.

In a very simplistic way, the rationale behind financing government spending with debt, is similar to you taking out a mortgage to buy a new house.

Sri Lanka’s Persistent Fiscal Deficits And The Need For Debt

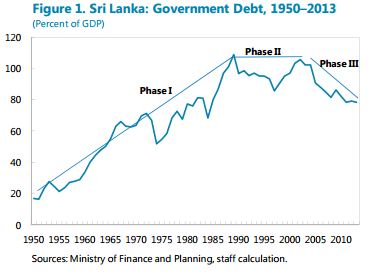

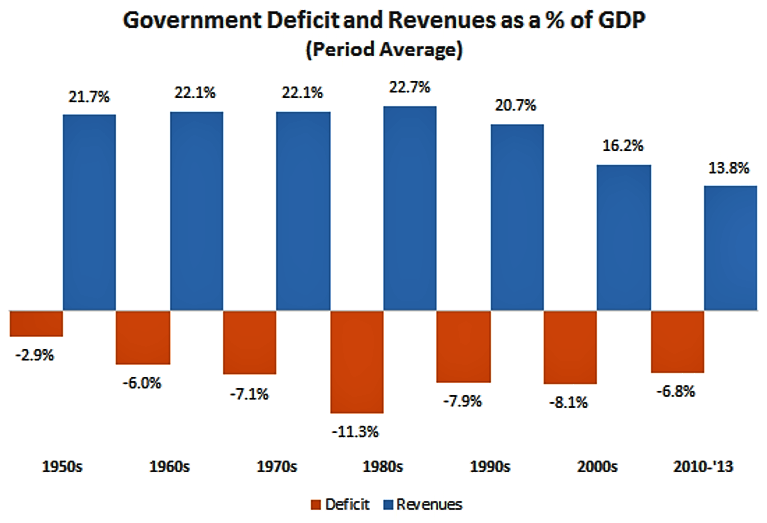

According to the IMF, Sri Lanka has recorded an average budget deficit of 7.2% of GDP between 1950 and 2013. During that whole period, budget surpluses were only recorded in two years,1954 and 1955. In simple terms, in almost every year since 1950, the country has had to borrow a lot of money in order to pay for its expenses. Do note that a deficit by itself is not a bad thing. Deficits caused by reckless spending, for instance, are bad, while deficits caused due to capital spending are generally regarded as good ‒ as long as the investments generate positive returns, obviously.

Here’s a chart of Sri Lanka’s government debt, as a percentage of GDP (from the same IMF report):

Image credit: IMF & MFP-SL

For the purpose of this article, ignore the different phases marked in the graph. But do focus on the rapid rise in government debt since 1950.

What Drives The Debt?

Government debt is necessitated by fiscal deficits. And since Sri Lanka has persistently high fiscal deficits, what are the reasons for it?

There are two broad reasons behind this problem, each relating to either the revenue or expenditure side of things.

Low Government Revenue

Perhaps the single largest factor which necessitates Sri Lanka to borrow is its low Tax-to-GDP ratio. As supra-national bodies like the IMF, and many other independent analysts have frequently said, the country’s tax revenue is much too inadequate to meet its expenses. Therefore, the Government ends up having to borrow far more than it would’ve borrowed, had tax revenue been at a more reasonable level.

Government Deficit and Revenues as a % of GDP. Source: IMF/ MFP-SL

Unsustainable spending

Successive governments have been guilty of this. Also, there are a lot of things that can be said regarding the country’s inability to spend prudently. For one, Sri Lankan policy makers have a tendency to view the budget as a ‘pot of cash’ and often provide handouts left, right, and centre to certain sections of the public, at the expense of all the other taxpayers. Going by recent experience, these usually take the form of excessively generous subsidies or across the board salary hikes, all done with a view towards the next election. However, this is not to say that subsidies and pay hikes are bad. Certain sectors like teaching and healthcare do deserve their pay hikes, given how overworked their employees are, and their importance to the overall economy.

Image Credit: M.Munaf-The Sunday Times

Another example would be the continued reluctance to tackle waste, mismanagement, and inefficiency at loss-making State Owned Enterprises (SOEs), particularly at utilities like the CEB and the CPC. Instead of tackling these problems head on, the Government bails out the SOEs every once in awhile, again at the expense of the taxpayer. Of course, bringing about change in such institutions is never going to be easy when considering their culture, and the influence of unions who, by nature, tend to be very resistant to change. But the most glaring issue is the lack of professional managers who can take an axe to the lethargic culture of these institutions, and drive change, thereby guiding them towards profitability. One thing worth noting is that SOEs may report improved performance in 2015/16, since they would’ve received the benefit of falling global commodity prices. The opposite happens when prices start rising. (SOEs can be transformed into world class players, when done right, privatisation is just one more option. Find out more by clicking here, here, and here)

The Greater Good, by Kashif Mateen Ansari

When confronted with the issue of reducing the deficit, policymakers have always opted for blindly raising taxes or imposing new ones, which, in a way, are rather convenient ways of ‘kicking the can down the road’. More often than not, these ideas for new taxes turn out to be very bad. One such bad idea was the imposition of an export tax on cinnamon (Unless you have market power, export taxes are generally a bad idea). The recent one-off, retroactive tax on “Supernormal profits” is also another case in point (it violates the principles of taxation, and is a one-time income stream used to finance a recurrent cash outlay, like the public sector salary hikes). Even on that rare occasion when someone gets a tax right, significant leakages occur due to various reasons like weak tax administration, and the practice of handing out tax holidays without restraint.

Sri Lankan policy makers trying to fix the economy be like:

Simply put, it is the inability to institute tax reforms, rationalise government spending, and the reliance on short term, stop gap measures which are at the heart of the problem. In other words, there is an urgent need to tackle the underlying fundamental issues affecting the economy.

All Arrows Point To Fiscal Consolidation

Agencies like the IMF have been warning Sri Lankan policy makers for ages about the need to tackle the hard problems. From the improper targeting of fuel subsidies to the undesirability of reducing capital and infrastructure spending in order to meet budgetary targets, the agency has continuously sounded the alarm (and made suggestions to solve those issues without causing much pain to the economy). Add to this the multitude of independent analysts and think tanks who’ve pretty much said the same thing, and one can only wonder why their advice hasn’t been sought and implemented.

But all that is in the past, and now we’ve got a problem that needs to be urgently dealt with, and it does not make sense to hypothesise about what the country would have looked like today if this or that had been done.

Instead, it is time for everyone to learn their lessons, put their brains together, and come up with a blueprint to achieve meaningful fiscal consolidation. But, it will definitely require a bipartisan approach from the individuals occupying the state’s legislature. Indeed, this is not the time for political grandstanding.

One need not wonder whether this spells doom and gloom for Sri Lanka. The little island nation has shown an astonishing ability to overcome adversity. The country has a clean debt service record. Also, its economy somehow grew by an average of 4% per year during the 90s, despite a war that raged heavily. That in itself is a very impressive achievement. The country does have the capacity to get back on the right track. But just like how talent is nothing without hard work, opportunity and ability will be nothing without action.

All this and more point to the fact that despite whatever challenges may come, Sri Lanka is going to be just fine in the long run. Sure, in the short run, a well thought out fiscal consolidation strategy is going to be painful for everyone (and not to mention, politically challenging). But it is much needed medicine for an ailing economy.

Cover image courtesy: siasat.pk