Anyone who has done geography or environmental studies, even at a school level, would know about how delicate and interconnected our ecosystem is. We’ve all heard of animals and plants that have become extinct or are endangered due to factors such as habitat loss and environmental changes, and the subsequent damaging effects on the overall environment. While growing up, we’ve recited lists of exotic animals like the Dodo, Tasmanian Tiger, Caspian Tiger and the Great Auk – but it always seemed so distant because it was all happening so far away and so long ago.

The truth is not as comforting. Sri Lanka is known as a biodiversity hotspot. To a certain degree, it may seem that we’ve managed to preserve our forest cover (which, in reality, is not the case, as our forest cover has more than halved since Independence). Everyone is talking about our wildlife safaris, whale and dolphin watches, and elephant rides etc., yet the truth is bleak. Going by the latest National Red List (2012), published by the National Botanical Gardens, Peradeniya, there is a large number of fauna species either critically endangered, endangered or vulnerable, and it’s all happening on a little tear-drop island in the Indian Ocean.

Where we stand

Amphibians

According to available data, out of the 34 species of amphibians “confirmed as extinct worldwide in the past 500 years, 21 are from Sri Lanka.” The number was finally brought down to 19, with the rediscovery of two species. While amphibians are not exploited for commercial use, significant habitat loss is the main threat. “The vast majority of the amphibians are restricted to the south-western wet zone quarter of the island (Dutta & Manamendra-Arachchi, 1996), where more than 95% of the original forest cover has now vanished,” the report read. Pesticide use, which is as yet unregulated and the threats to environmental health and impact on non-target organisms unassessed to date, is another concerning factor, along with air pollution. Of the total 111 species of amphibians in Sri Lanka, 73 are threatened.

Crabs

Yet another highly threatened group are the fresh water crabs. According to the report, “nearly 90% of the freshwater crabs in Sri Lanka are globally threatened with 66% being listed under the critically endangered category.” That means 46 out of 51 species are threatened. Sri Lankan crabs also show 98.04% endemicity, not observed in any other faunal group in Sri Lanka. Threats include invasive alien species, fertilizers and pesticides, local climate change, rainwater acidification and increased erosion leading to sedimentation of water bodies.

Bees

Faced by the decline and fragmentation of their natural habitats, as well as invasive grass species, 106 out of 130 species of bees are currently threatened.

Mammals

53 out of 95 mammals, excluding 30 marine mammals (excluded due to lack of data) are under threat. This includes shrews, bats, the Sri Lankan purple faced langur, the red slender loris, the leopards and elephants we are so proud of, the rusty-spotted cat, the fishing cat, sloth bears, civets, wild buffalo, hog deer, pygmy mouse deer, giant and small flying squirrels. Aquatic mammals like the sea whale, blue whale, fin whale and the sperm whale also face threats.

Reptiles

107 out of 211 species of reptiles, including marine reptiles, are under threat. This includes crocodiles, sea turtles, horn lizards, geckos and snakes.

Other

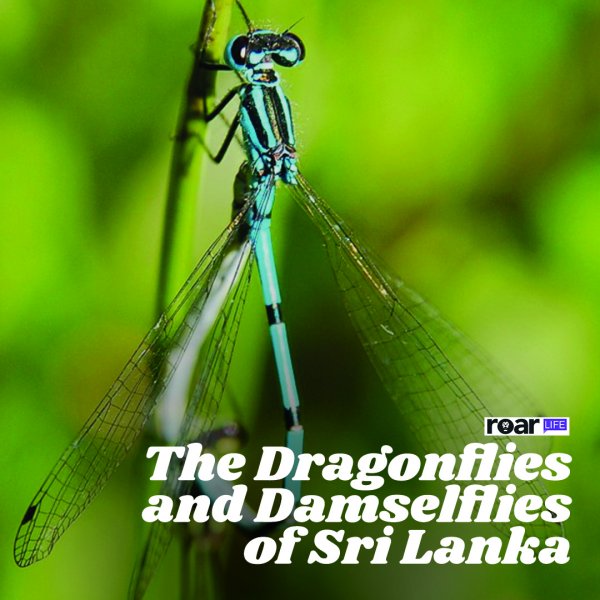

Fauna species like dragonflies (61 of 118 species), land snails (179 of 253), freshwater fish (45 of 91), birds (67 of 240), butterflies (99 of 245), ants (59 of 194) and spiders (62 of 501) also face threats.

The numbers are bleak – all the more when looked at under a microscope. Some are critically endangered to the point of being possibly extinct. This includes two fresh water fish species, one amphibian species and one reptile species. Others are critically endangered, like 41 species of spiders, 34 freshwater crab species, 26 species of dragonflies, 25 ant species, 48 species of bees, 21 species of butterflies, 80 species of land snails, 19 freshwater fish species, 34 amphibians species, 38 reptiles species, 18 bird species and 13 species of mammals. The list is further divided into endangered and vulnerable species as well as species not threatened. The report also identified areas where data is deficient, as well as species that are the least threatened in comparison.

In the report, Professor Devaka Weerakoon summarises it further.

“Of the surviving inland vertebrates, 122 species are Critically Endangered: i.e., one in every 6 species of inland indigenous vertebrates of Sri Lanka is currently facing a high risk of extinction in the wild.”

Among the total endemic vertebrate species, 92 (29%) are Critically Endangered, 98 (31%) are Endangered and 39 (12%) are Vulnerable. Among the vertebrate fauna, the highest number of threatened species was recorded among reptiles (107 or 31%), followed by amphibians, birds, mammals and freshwater fish. One in every two species of freshwater fish, amphibians, reptiles and mammals and one in every five species of birds in the island are currently facing the risk of becoming extinct in the wild.”

He further said that among the selected groups of inland invertebrate fauna evaluated, the highest number of threatened species was recorded among the land snails (179), followed by bees, butterflies, spiders, dragonflies, ants and freshwater crabs.

“However, within a single group of invertebrates evaluated, the highest proportion of threatened species was recorded among the freshwater crabs (90% of the total crab species recorded to date), where one in every two species in Sri Lanka is currently facing an immediate and extremely high risk of extinction (CR) in the wild,” he added.

But that was as of 2012…

…surely something would have been done by now, right?

Not really. Speaking to Professor Devaka Weerakoon, from the Department of Zoology, University of Colombo, also part of the supervisory team of the Red List, it was understood that the Red List only acts as the initial diagnosis – beyond that, however, not much has been done.

“We need programs for every Critically Endangered species, but much of that has not happened,” he explained. “Without that, the Red List will become a mere academic exercise,” he said, adding that the list should be accompanied by swift action, mostly on the part of the government.

Professor Weerakoon identified another problem: the lack of data. In the report, he pointed out that “among the inland vertebrate species evaluated, nine freshwater fish, one amphibian, 27 reptiles and six mammals were included in the Data Deficient category. Among the invertebrate species assessed, 394 spiders, 11 dragonflies, 109 ants, 06 butterflies and 36 land snails had to be included in the Data Deficient category, because they lacked sufficient distribution data within Sri Lanka. The number of species listed in the data deficient category is extremely high among the spiders and ants as very little information exists about members of these two groups.”

None of this sounds particularly encouraging – the numbers are against Sri Lanka. It would help greatly if we had strict regulations that were enforced, for instance, on whale watching, which is a huge money spinner. Likewise, strict laws on emissions, industrial waste and logging could help the situation immensely. Despite all the promotion Sri Lanka gets as a biodiversity hotspot, as the home of many endemic plants and animals, as an exotic location for safaris and eco-tourism, we need to have something to show – apart from a harrowing Red List, that is.