The words thalagoya and kabaragoya should sound familiar to anyone who grew up in Sri Lanka. Chances are, many of you may even have spotted one of these remarkable reptiles at some point in your lives.

The kabaragoya is what is known as the Asian water monitor or Varanus salvator, while the thalagoya is the Bengal monitor, or Varanus Bengalensis – although honestly, they’re locally better known as just kabaragoyas or thalagoyas.

The kabaragoya or water monitor is generally the bigger of the two. Image Credit: zoochat.com

As far as local reptile spotting is concerned, kabaragoyas and thalagoyas are the next best thing to crocs and snakes. These monitor lizards are an impressive sight to behold, and can venture quite close to human territory; closer to marshy areas, they sometimes even stray into home gardens. They are often easily confused with each other, but are in fact distinctly different. How so?

We spoke to herpetologist Dinal Samarasinghe to find out.

To begin with, the thalagoya, being a land monitor, is limited to land movements, while the kabaragoya is active closer to a water source. While both lizards can move around in the water, the kabaragoya is the one who prefers water over land (and is built for water movement).

For both species of monitor lizards, the main determinant in selecting habitats is temperature. They each have two different thermoregulatory strategies: the kabaragoya has to maintain a temperature of 29-31ºC, so if it gets colder, they go in search of warmer waters, or opt to bask in the sun.

The thalagoya, on the other hand, is known as a ‘thermoconformer.’ It has a broader active body temperature range (24/25-36 ºC), so it does not have to be as selective about its habitat.

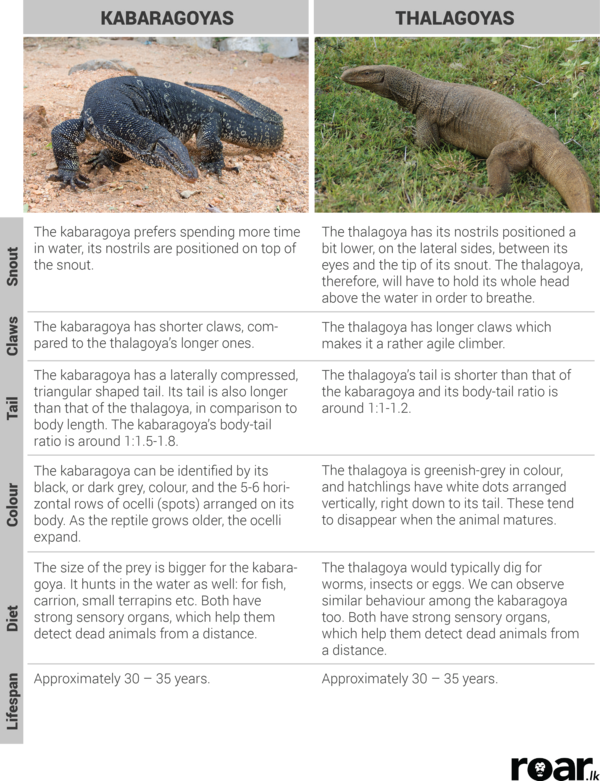

The two monitor lizards also possess a number of physical attributes that form a basis for telling them apart. Here’s a breakdown of characteristics they share, as well as ones they don’t:

A breakdown of characteristics they share, as well as ones they don’t:

As for who would win in a fight – the kabaragoyas are not just bigger, but are also known to eat thalagoyas should they feel inclined to do so, and that just about answers the question.

Although both reptiles are known to be distributed across the South Asian region, the kabaragoya we find here in Sri Lanka (Varanus salvator salvator) is in fact an endemic subspecies of water monitor. The kabaragoya also boasts a bit of interesting legal history – it was the first reptile to be protected under the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance of 1937. The largest water monitor on record (3.21 metres) was also from Sri Lanka.

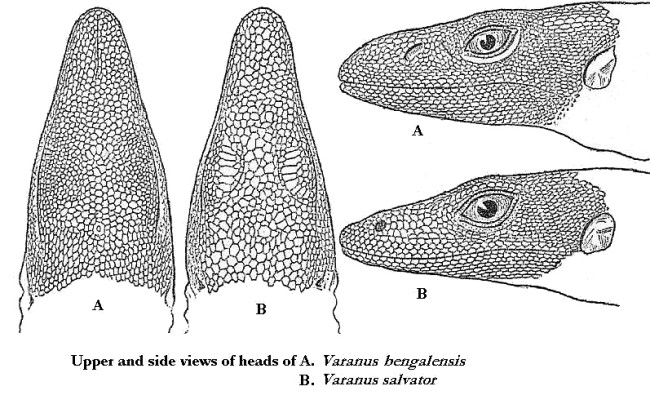

Some physical differences. Image credit payer.de

The kabaragoya has an interesting social structure. These creatures prefer habitats close to a water source, and, as is the case with many animals, there is likely to be one male of the species who dominates a particular habitat. Subordinate male kabaragoyas are then chased away from the water source or main habitat, and forced to disperse. In and around urban areas, kabaragoyas may thus have a tendency to stray closer to human habitats, such as into home gardens. The females, meanwhile, often move about 200 – 300 metres away from their water source to lay eggs.

The thalagoya comes with its fair share of fun facts: such as, its flesh is known to be edible. In Sri Lanka, thalagoya curry is not entirely unheard of, and one does recall reading about how two characters in Nihal de Silva’s novel, The Road From Elephant Pass, captured, killed, and dined on thalagoya while hiding out in the jungles of Wilpattu.

The thalagoya, or land monitor, is a pretty agile climber. Image Credit Dinal Samarasinghe

Interestingly, that wasn’t the first – or only – time the thalagoya, or even the kabaragoya for that matter, was offered a place in English literature. The two words have become as Sri Lankan as the creatures they name, and several authors haven’t been able to resist inserting these words into works based in or pertaining to Sri Lanka. This article by Richard Boyle for instance lists out the kabaragoya’s and thalagoya’s many forays into English literature, dating back to the 17th century. Writers including Robert Knox, Gordon Cumming, Michael Ondaatje and Carl Muller have spoken of these creatures in their works. Another instance that has not made it to the article, is the thalagoya encounter in Amitav Ghosh’s The Shadow Lines. The characters in this novel react in a way that most of us probably would when encountering the reptile – that is to say, they freak out.

A water monitor (kabaragoya) strays close to a residential area.

As intimidating as they may look however, these monitor lizards are relatively harmless unless confronted directly. If one of them is cornered, chances are they will first try to make themselves look as big and intimidating as possible. The reptile may even raise itself up and hiss menacingly, their way of saying “stay away from me!” If, despite all this, you still try to get closer, there is a great chance the thalagoya or kabaragoya would curl up its tail and use it as a whip; and as mentioned before, this could do some serious damage – especially the tail of the kabaragoya, which has a ridge on the top.

Sadly, human activity of late has proven to be less than beneficial to the monitor lizards – according to Dinal Samarasinghe, there has been notable destruction of their habitat in recent times. There have also been incidents of thalagoya and kabaragoya deaths caused due to road accidents. In fact, given recent urban developments around marsh and wetland areas, it would be safer to say that we are of more danger to the thalagoya and kabaragoya than they are to us.