From clusters of mangroves which can be found near the island’s lagoons, to the cloud forests atop its highest hills, Sri Lanka is a country with a wide array of ecosystems. Yet, there is one particular ecosystem which has rarely been spoken of within the country: natural caves.

Formed over time through a combination of various factors—such as the rate of weathering and erosion, the climate and the type of rocks and minerals present in an area—caves are a topic of interest to archaeologists, both local and foreign. In Sri Lanka, the remains of early humans and the tools and objects that they used have been unearthed in natural caves, some of which are said to be millions of years old.

Cave tourism—a form of tourism which has become quite popular in the West—seems to be catching on in Sri Lanka. A few months ago, a group of divers belonging to a group called Dive Sri Lanka, decided to explore the tunnels of the Ravana’s underwater caves in Ella.

According to Dr. Wasantha Weliange, a leading speleologist who provided assistance for this expedition, this cave is by far the largest to date discovered in Sri Lanka. Roar Media spoke to Dr. Weliange to find out more about these dark, mysterious places.

Exploring The Country’s Caves

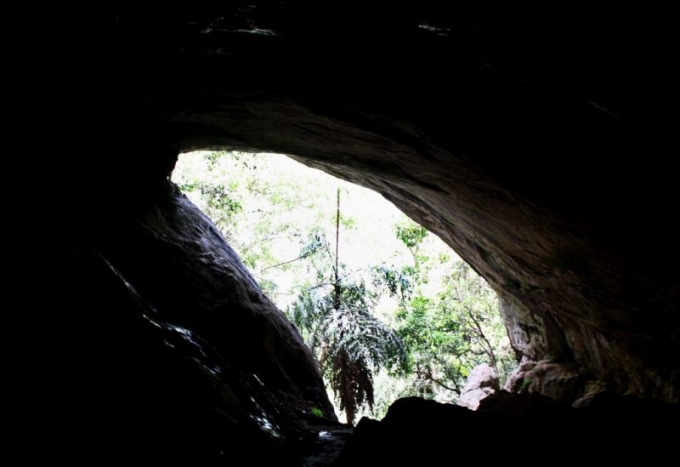

Inside the Ravana Cave in Ella—this cave is fabled for being the place where the legendary King Ravana built his palace. Image credit Roar/Sachin Bhandary

Right now, Dr. Weliange, who is attached to the Lanka Institute of Cave Sciences (LICAS), is currently working on a project—along with Biodiversity Sri Lanka and Dilmah Conservation—to explore the unexplored caves of the country.

According to him, there are two major types of caves in Sri Lanka—terrestrial rock shelters and underground caves. “Some underground caves are so elongated [they are] called tunnels. Various historical reports say [that] there are about 250 caves in Sri Lanka. LICAS has so far explored about twenty underground caves and about ten rock shelters,” stated Dr Weliange.

One such historical account was written by the ancient Arabian merchant and traveler Ibn Battuta; he wrote in his diary that he spent his nights in seven rock shelters along his journey to the summit of Adam’s Peak. “During this project we may cover about fifteen underground caves,” Dr Weliange revealed.The project brings together biologists, speleologists, geologists and academics from other fields in order to survey these caves, describe their geology, map them and search for and document the organisms which dwell in them.

Caves Vs Other Ecosystems

Dr. Weliange told Roar Media that many interesting creatures have been discovered so far, but exact details could not be given as his team is still in the process of identifying these species. Image credit Dr. Wasantha Weliange.

According to Dr. Weliange, while most terrestrial and shallow-water habitats receive at least a few hours of sunlight within a day, all year round, habitats like caves receive very little to no sunlight at all.

Even though the harsh conditions of these caves do not allow terrestrial plants and creatures to live and grow within them, these places are not completely devoid of life, for several species—each with their own unique adaptations to cope with this underground ecosystem—have been discovered, abroad and within Sri Lanka as well. The caves are home to not just bats, but a couple of species of insects and other small creatures, unique to this environment.

“The energy emitted by the sun has a range of electromagnetic waves—low frequency electromagnetic waves, high frequency electromagnetic waves and the visible sunlight. None of these types of energy enter into caves, yet even in this perpetual darkness life still flourishes,” said Dr Weliange.The first phase of the project that Dr Weliange is currently occupied with began with the exploration of the Sthreepura caves in Kuruwita. These caves are thought to be over a thousand years old, even though their exact geological time frame is not known. “[So far] We have discovered more than a hundred different species of animals, including millipedes, frogs, centipedes, spiders, ticks, mites, flatworms, beetles, moths, cockroaches and several species of tiny bats,” Dr. Weliange said. “We are still in the process of identification and cannot give any more details about them, but we know that there is a complex and unique network of energy transfer—the food web [that] occurs within [these] dark caves [are] made up of hundreds food chains,” he added.

Deep, Dark And Unexplored But Still Important

Caves provide homes for bats, and they indirectly they help sustain food security within the country. Image credit Dr. Wasantha Weliange.

Dr. Weliange also revealed that natural caves are important in terms of food security and a sustainable economy.“Caves are directly related to crop production,” said Dr Weliange. “Because [they] provide homes for tiny bats who eat insects—most of those flying insects are pests [which harm] agricultural crops. When [there are] more caves, the population of tiny bats increase and insects can be controlled naturally. On the other hand, these tiny bats are pollinators too,” he added.

The provision of a habitat for these bats, which help to keep the number of harmful pests at bay, is one of the most important functions of natural caves. In the long run, it ensures that farmers and others involved in agricultural activities can limit their use of harmful pesticides.

Exploring, surveying and documenting many of the natural caves is time consuming and require a lot of effort and equipment.

Dr. Weliange and the other members of this team hope that the work they contribute towards will ensure that these caves—which are currently not protected under any of Sri Lanka’s environmental laws—will be legally protected in future.

Featured image: Cave experts exploring the depths of Waulpane, a cave located in the Bulutota Rakwana mountain range in the Ratnapura district, which is home to a large population of bats.

Cover: The Kosgala cave in Ihalawatta, Ratnapura. Image credit Dr. Wasantha Weliange.