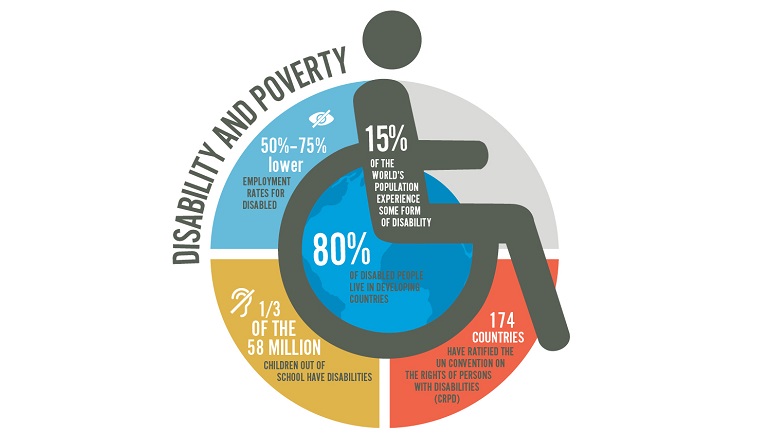

Around 15% (or 1 billion people) of the world’s population lives with some form of disability. According to a WHO report, roughly 2-4% of the community lives with debilitating conditions and severe difficulty functioning.

Over the recent years, it has been noted that the number of people with disabilities has increased, owing to an ageing population and a global rise in chronic health conditions (diabetes, mental illness, cardiovascular diseases, etc.). The current number is higher than the 1970s World Health Organization estimates, which was around 10%.

Trends in health conditions, environmental factors, and others, such as road accidents, natural disasters, conflict, diet, and substance abuse, have been acknowledged in the report as contributing factors to this increase.

The study also posits that people with disabilities around the world have poorer health outcomes, lower education achievements, less economic participation, and higher rates of poverty than people without disabilities.

Barriers in terms of accessing services that are freely available to abled people are partly responsible for this divide, which include health, education, employment, information, and transport.

According to a survey conducted by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs – Division for Social Policy and Development, poverty and disability go hand in hand, with disability being both a cause and a symptom of poverty.

For example, people with disabilities are at higher risk of losing their sources of income or jobs, and therefore, more likely to experience poverty. On the flip side, those who live in poverty are less able to obtain proper healthcare and therefore more likely to have their health adversely affected. Thus by empowering people with disabilities, poverty eradication is made more feasible. But why is this not yet a reality?

Stigmatised

The situation is notably worse in less advantaged communities, such as those in Sri Lanka.

Stigma plays a major part in preventing people with disabilities from accessing proper education and employment, according to a 2018 International Centre for Ethnic Studies (ICES) report.

Participants in the study explained that many parents would ‘hide’ their children with disabilities, often confining them to the house for fear of social backlash against the family.

Having a family member with a disability could effect consequences upon other members, even affecting one’s marriage eligibility.

People with disabilities are often targeted, harassed, abused, and or exploited. These further hinder them from participating in society as active members.

Education And Employment

In Sri Lanka, about 96% of the total population with functional difficulties don’t engage in educational activities. Around the country, only approximately 54,311 students with disabilities attend school.

According to IPS (2016), there are 88,740 children with intellectual and physical disabilities, aged 5-19, of which 62% received education through mainstream schooling, and 34% have not received any form of education. These numbers highlight how for children with more severe functional disabilities, the Sri Lankan school system lacks the fundamentals to accommodate and cater to their needs.

The lack of a formal education means these children are not equipped with the necessary knowledge nor are given the appropriate skills to navigate society. This often leaves them as dependents on family members rather than independent individuals who are self-sufficient.

By denying them quality education, they are also being denied their agency and their ability to provide for themselves.

Education aside, the employment sector is not doing any better in terms of inclusion either. According to the study conducted by ICES, Sri Lankan employers are hesitant about hiring persons with disabilities regardless of their educational qualifications, often reducing them to their disabilities rather than seeing them as individuals with different capabilities.

The study’s respondents from organisations that handle employment for persons with disabilities expressed how common it is for employers to assume that people with disabilities are ‘only fit for blue-collar jobs’.

Accessibility

With most buildings in Sri Lanka being unconducive for people with physical disabilities, as well as inefficient public transport, accessibility has a major barrier. Up until a few years ago, wheelchair ramps were a rare sighting in the country, and many public spaces still lack access points for wheelchairs.

Unfortunately, accessibility has been compromised in other ways, too. Country Coordinator for MyRight Asanga Ruwan Perera highlighted that the hearing impaired are “disadvantaged by the lack of sign language interpreters” in the country, going on to note that they have to learn a version of sign language unique to their area of residence, which in turn “impedes their communication when interpreters are available”.

He then opined that children who are hearing impaired are more often the ones to teach their teachers sign language, due to the severe lack of teachers qualified in sign language. These disparities lead to impediments in the child’s communication and intellectual development.

Technology is also becoming increasingly inaccessible for people with disabilities, as almost every new application or device fails to take into account potential customers with disabilities across the spectrum.

Though there are a few startups that have innovated new methods through which people with disabilities can utilise technology to make communication easier, the vast majority of technology is simply not catered to them.

Amongst the community, women with disabilities are further marginalised as they are subjected to multiple different levels of discrimination, from sexual and gender-based violence to not being provided an education simply because they are women.

As they are caught in a claustrophobic cycle of striving to break free of limitations placed on them by society, they have to fight for their education, reproductive rights, employment, and against sexual violence, among others.

Much To Be Addressed

Towards the end of March 2020, the state imposed a string of curfews, which were suddenly lifted and reimposed over the next several weeks, with some high-risk areas in Sri Lanka going under prolonged lockdown.

In such uncertain times, says Rasanjali Pathirage from the Disability Organisations Joint Front (DOJF), the disability community was impacted negatively, not just in terms of basic resources but in terms of discourse, policy, and aid.

“Whenever curfew was lifted to allow people to get groceries, individuals with disabilities faced problems because they couldn’t venture out like the rest of the public; especially the visually hindered persons or those who are restricted to wheelchairs. Some of these individuals who live in rural areas take a long time to travel to the closest shop. Even if you had money, it was a problem,” Rasanjali explained.

In addition to this, individuals with disabilities who had set up their businesses by the roadside selling lottery tickets and handcrafted items, among other things, lost their livelihoods. There were even instances where they never received rations and medication that were meant for them, lamented Rasanjali. Those who were deaf or hard of hearing were left helpless as most of the communication was happening over phones and they could not contact anyone.

DOJF had done whatever it could to aid the disability community in the meantime, but there was still so much that needed to be addressed. When disseminating key information, government sources did not consider including a version in sign language.

Even the media, while covering the situation on ground, often did not acknowledge much of the issues faced by the disability community, or they cut out the sign language interpreters at official press conferences.

“On top of that, there is no proper database that registers the number of people with disabilities in the country, documenting the nature of their disability, etc. It’s a simple task,” Rasanjali added.

“Same when it comes to disaster strategies; whenever floods, landslides or some other natural disaster happens, there are strategies in place for the general public to follow. But what kind of steps should you follow if you’re an individual with a disability? That has never been discussed.”

When it comes to COVID-19 precautionary guidelines, the situation remains as stale. The Health Ministry’s guidelines did not take into consideration the fact that many in the disability community require caretakers and cannot truly practice social distancing, or that visually impaired individuals cannot maintain a metre’s distance.

While acknowledging that the Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic has been good, Rasanjali raised concerns regarding the lack of mention of any long-term plans to address the disability community’s issues. “How can leg amputees wearing prosthetic limbs operate those sinks that require using one’s foot?” she asked, highlighting one of the key oversights that need addressing.

Empowerment

As the economic gap between abled people and people with disabilities widens, the economy itself is bearing the brunt of the blow. The number of people living in poverty who are disabled is increasing due to abandonment, lack of access to appropriate services, lack of a formal education, or employment opportunities; and there is a glaring dearth of inclusiveness when it comes to people with disabilities in policymaking and essential sectors that would give the community a say in society.

Poverty is multifaceted and is in no way a one-solution issue, but a major step towards eliminating poverty would be to empower one of the largest segments within society who experience it—people with disabilities.

The key focus when it comes to empowerment of people with disabilities should be to ensure they have the means to live independently while participating in society as active contributors. In order to successfully integrate people with disabilities into society, first the social stigma against disabilities needs to be stymied.

Following this, focus then needs to be placed on developing clearer and more consistent coverage policies, improving the local education system, making public transport more accessible, and ensuring persons with disabilities are provided equal services and fair employment opportunities.

.png?w=600)