This is the third in a series of photostories illustrating the history and decline of Colombo’s “adult film” cinemas. The popularity of these cinemas peaked in the 1980s and ’90s, as imported pornographic movies proved popular with local audiences and guaranteed profits for film halls. With time, increased social conservatism and the widespread availability of “adults–only” content online sent these cinemas teetering to the brink of dissolution, where many still remain. The first of the series can be read here, and the second here.

The first “adults-only” movie screened at Rio Cinema — according to owner Ratnarajah Navaratnam — was technically West Side Story (1961). “It was one of my all-time favourites. Still is,” he told me over the phone. “The censors then made it adults-only, because there were two gangs — the whites and the Puerto Ricans. There was no violence; it was [based on] a play. But we weren’t very strict about the adults-only [rating]. I saw it about forty or fifty times.”

When the Rio Cinema was opened by Navaratnam’s father, Appapillai Navaratnam, in 1965, it swiftly became an immensely popular enterprise. The first 70mm Todd-AO cinema in the country at the time, the cinema screened back-to-back Hollywood blockbusters — South Pacific (1958), Can-Can (1960), The Alamo (1960), Cleopatra (1963), The Sound of Music (1965) — “all the big movies,” as Navaratnam puts it. The 600-seat cinema was overwhelming by the standards of the time, with a screen stretching from wall-to-wall and almost to the roof. “People used to come out and say they had a neck pain from looking up, because the screen was so big,” said Navaratnam.

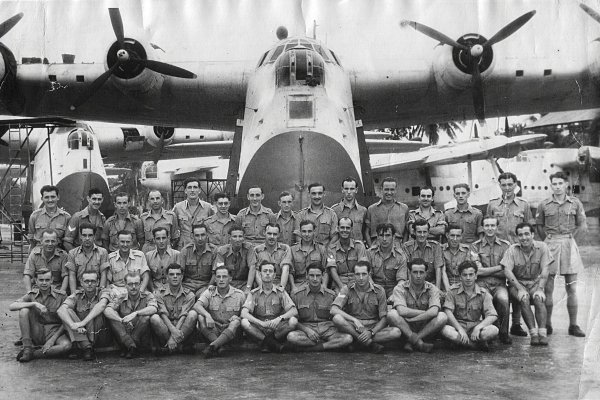

Popularity and prestige often go hand-in-hand, as was the case with Rio, which hosted no less than three future presidents at its opening: The cinema was officially declared open by William Gopallawa, then Governor-General of Ceylon, and soon to be Sri Lanka’s first president, and attended by his eventual successor, J.R. Jayewardene. In the audience of its first ever screening also sat a young girl who would go on to be the country’s fifth president, legs and arms crossed and staring straight ahead. That framed black-and-white photo of a young Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga hangs inside the small office on the ground floor, one of the few items salvaged from the fire that engulfed the cinema and adjoining hotel in 1983.

Next to the office, double doors labeled ‘AIR CONDITIONED’ lead to a hallway built to accommodate what must have once been an impressive confectionary stand, and the crowds that formed around it before screenings and during intermissions. To its credit, Rio has not yet fully given up the charade — inside a glass cabinet lie no less than eight packets of peanuts and two plastic water bottles…just in case.

Past the hallway is the cinema itself, with its towering screen, Many of the red leather chairs are now pushed off to the side, dust settling on nearly every available surface. In the late ’60s and early ’70s, Navaratnam said, the hall would be populated with families. “Those days, [the] cinema was a family outing. Even when I was in school, O/Levels and all that, I would go for movies with my parents,” he said. The busiest showtimes, he recalled, were the 9:30 shows on Friday and Saturday nights, when parents would ring up to reserve tickets for themselves and their children to see whichever family-friendly feature was showing that week.

Things changed when the National Film Corporation, formed in 1972 under then-Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike, monopolised film distribution. “When the [National Film Corporation] came, the Hollywood film suppliers — 20th Century Fox, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Paramount — all refused to supply films to Sri Lanka because they said they don’t deal with monopoly anywhere in the world,” said Navaratnam. “So there was a huge vacuum, a huge lack of films at one point.” As a result, Rio began to source films from independent suppliers — films that were passable at best, disreputable at worst.

Evidence of the latter variety remains all over the cinema. Opposite the makeshift confectionary stand, a poster for the film Ideal Marriage shows a couple seated and gazing at each other, clearly naked. Another one, for a film called Hot Chilli, features the tagline ‘HOT SUN… HOT SAND… HOT SEX…’. Halfway up the staircase, the plot for Vengeance is anyone’s guess based on the poster, which depicts a nude and solemn young woman, a couple kissing in a body of water, and four people jumping in the air in poses that range from violent to joyful.

For Navaratnam, these films were a last resort. “We never imported adult content movies, we just got them from the distributors to keep the cinema going,” he said. The National Film Corporation, according to Navaratnam, put a swift end to Sri Lanka’s burgeoning cinema-going culture. “The cinema culture changed totally,” he said. “[The audience] was mostly youngsters, families were no longer going to the cinema, because the cinemas didn’t have good movies.”

Then came the pogroms. In July 1983, mobs — members of which included the Navaratnams’ neighbours and wider community — looted and set the Rio complex on fire. Navaratnam’s father never recovered from the loss. “You know, you make a bad decision, you lose your business, that’s different,” he said. “But to work hard, brick-by-brick, to earn this, and then to see it going up in smoke and the government doing nothing about it — that was the saddest part.”

Since then, the complex has remained in a state of general ruin and disarray but has become a popular choice of venue for art festivals, video shoots, plays, and even wedding photoshoots, according to Navaratnam. “This kind of a look seems to be in vogue now,” he said.

Even as a skeleton of the building it once was, Rio’s faded grandeur, tragic history and stubborn permanence have cemented its status as a Slave Island landmark — a monument of sorts in an area that has recently fallen victim to increasing gentrification. Navaratnam remembers an Air Force checkpoint stationed close to the cinema during the war, colloquially nicknamed ‘Checkpoint Rio’. “One day I was stopped somewhere by the Air Force, and they asked where I work. When I said I was the owner of Rio Cinema, they said, ‘Ah! Mahattaya Rio Checkpoint lange de?’,” he laughed. “It was a real landmark.”