After the Matale Revolt of 1848, the independence struggle in Sri Lanka was quiescent until the 1930s. Only in 1931 did the short-lived Jaffna Youth Congress call for total independence (poorana swaraj) and boycotted the general election.

However, in far-away America, a young Sri Lankan student, Philip Gunawardena, had already joined the League Against Imperialism and For National Independence, an international organisation committed to the complete national independence of the colonial and semi-colonial peoples, including Sri Lankans. He later went to Britain and worked for the League. He belonged to a Sri Lankan group called the “Cosmopolitan Crew”, mainly students such as himself, including N. M. Perera, Colvin R. de Silva and Leslie Goonewardena.

Cosmopolitan Crew: Philip Gunawardena, Colvin R. de Silva, and N.M. Perera. Image courtesy Victor Ivan

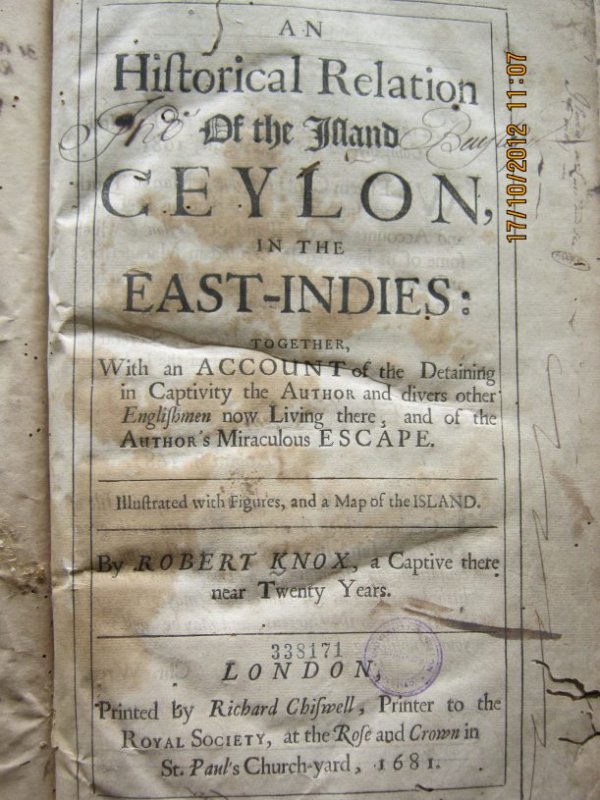

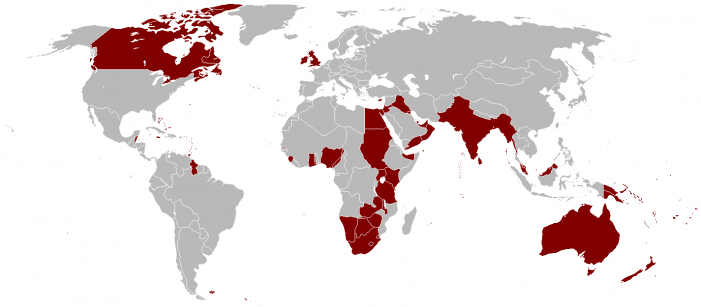

In the early 1930s, members of this group, imbued with ideas of socialism and nationalism, began trickling back to the island and began anti-British agitation. In 1935, they formed the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (L.S.S.P.), the first modern political party in Sri Lanka, with total independence from Britain on its agenda. The L.S.S.P. contested four seats in the 1936 general election, getting two of its candidates, Philip Gunawardena and N. M. Perera elected to the State Council. They immediately began using the legislature as a platform, bringing up such issues as the use of Sinhala and Tamil instead of English for official purposes. However, it was not easy to put the issue of national independence on the political agenda. Sri Lanka was a very different country then. Popular opinion had it that the British Empire, “the empire on which the sun never sets”, then at its greatest extent—covering a quarter of the globe’s land surface and a fifth of its population—was impregnable.

The British Empire at the time of the Bracegirdle Incident. Image courtesy Wikipedia

This writer’s father told him that, at the time, almost all middle-class households displayed pictures of the King and Queen of England prominently in their living rooms and displayed the Union Jack at their weddings. The working class and peasantry were willing to fight for their day-to-day needs, but independence was a far cry indeed. The leaders of the elite were firmly ensconced in a vision of a better place for themselves under the benign eyes of the British Raj. As late as the early ’30s, the ministers submitted a memorandum to the colonial government, seeking to increase their own powers and not even demanding dominion status, let alone independence.

The L.S.S.P. needed a symbol to project itself and the struggle for independence onto the popular consciousness. It found this in a young Anglo-Australian planter called Bracegirdle.

Bracegirdle Steps Forth

Mark Anthony Lyster Bracegirdle, born in London on September 10, 1912, migrated with his mother (a prominent suffragette and former Labour Party local-government candidate) and brother to Australia. In Sydney, he studied art and then went to the outback, where he trained as a farmer. In 1935 he joined the Communist Party of Australia. On April 11 the following year, he sailed for Colombo on the Bendigo.

The late Hector Abhayawardena, chief theoretician of the LSSP, told this writer that he suspected that Bracegirdle was sent to Sri Lanka on the instructions of the Comintern, the international organisation of Communist Parties, in response to the situation in Sri Lanka. Australian journalist and diplomat Alan Fewster, who wrote a book about him, thought he had been sent as a Stalinist agent to wean the fledgeling party away from Trotskyism. However, Bracegirdle himself denied this, giving as his reasons for coming to the island:

“Well, mainly the fact that I was going to learn a new type of agriculture, but nothing really political at that time. I had no knowledge of the politics of Ceylon.”

Mark Anthony Lyster Bracegirdle. Image courtesy Alan Fewster

On board ship, Bracegirdle met Mary Elizabeth Vinden, a young Anglo-Australian socialite, going on holiday to Britain. The couple fell in love. However, duty called. On April 4, he disembarked at Colombo, while Mary continued to London.

After a brief walking tour of Colombo Fort, Bracegirdle took a train upcountry. He went to Relugas Estate in Madulkele, in Matale District, where he began “creeping”—learning how to manage a tea estate—under Superintendent H. D. Thomas, whose family had been planting in the area since “coffee times”.

Together with another “creeper”, Robert George Simpson-Hayward, the son of the renowned under-arm test bowler WHT Simpson-Hayward, he began experimenting with innovative agricultural techniques, which they persuaded Thomas to adopt. However, it was his experience of the conditions of the estate workers which really jolted him.

Planter Raj

The planters, almost all white, formed a tiny, privileged minority in the estate areas. They lived in relative luxury on plantation bungalows, with servants at their beck and call, meeting other planters in “whites only” clubs. The country was pretty much run for their benefit.

This pally system of governance came to be known as the “Planter Raj”, the estates almost forming a separate kingdom on its own. Here, planters were treated as gods, the labourers having to crouch in drains whenever they passed. Young women workers were forced to submit to their sexual advances.

On the other hand, the workers, the “estate coolies”, lived in wretched conditions. Estate owners contracted ‘kanganies’ to bring them labour gangs of Tamil and Telugu peasants from South India to work there. The kanganies were not too choosy about their recruitment practices, press-ganging some and buying the debts of indentured labourers, who had then to work off their debts on the estates.

Most of these coolies had to trek across South India and northern Sri Lanka to estates, tens of thousands dying on the journey—as well as later, on the plantations. They were treated inhumanely, receiving very little healthcare or education, forced to live in “line rooms”, worse than cattle sheds.

Old line rooms at Relugas. Image courtesy writer

Bracegirdle’s employer was fairly typical. According to Wesley Muthiah, co-author of a compilation of documents relating to the Bracegirdle affair, Bracegirdle told him that Thomas would “go to the line rooms to force workers to go to work”.

“Despite many labourers having malaria or suffering badly from its effects,” he said, “he would insist on them picking tea.”

Thomas was also typical in his attitude to education for the coolies, forcing children to go out and pluck tea, rather than attend the estate school.

“It is better that they should learn to pick tea,” Bracegirdle reported Thomas as saying. “Learning to read and write was only copying white men, and it does them no good at all and will give them ideas in later life above their station.”

Bracegirdle Joins The L.S.S.P.

Mark Anthony Lyster Bracegirdle. Image courtesy Vijith Gunawardena

Coming from the relatively egalitarian society of Australia, the treatment meted out to the Indian Tamil estate workers appalled Bracegirdle. He went down to the line rooms and “fraternised” with the coolies, even sharing meals with them, for which Thomas admonished him.

However, Bracegirdle was stubborn. Labour trouble brewed up on the estate, with Thomas firing several workers, and he took the workers’ side. He was himself unceremoniously sacked, and he was given a ticket to return to Australia by steamer.

Meanwhile, Simpson-Hayward had introduced him to Vernon Gunasekera, secretary of the L.S.S.P. The party had sent Leslie Goonewardena to Kandy to meet him. The prospect of a white planter propagandising against the white Plantation Raj seemed too good an opportunity to be missed. Bracegirdle went down to Colombo and joined the LSSP, becoming an activist.

Bracegirdle with L.S.S.P. leaders in Horana. Image courtesy Victor Ivan

He wrote an article, “The Australian Youth Today”, for the November edition of The Young Socialist magazine, under the pen name “Tony Price”. The Police took note of this, and the fact that he was now living with Vernon Gunasekera.

A Criminal Investigations Department (C.I.D.) minute to Inspector General of Police (I.G.P.) Philip Norton Banks remarked that the L.S.S.P. wanted him “as a ‘Communist placard’, so much as to say ‘Here is an Englishman, who is a Communist, learn Communism from him.’”

The impact of a white man participating in anti-colonial activities, at a time when white supremacy was taken for granted, could not be gainsaid, and the L.S.S.P. emphasised this at every opportunity.

On November 28, Colvin R. de Silva, the president of the L.S.S.P., introduced him at a public meeting in Maradana, saying “This is the first time a white comrade has ever attended a party meeting held at a street corner.” Thereafter, he helped to organise a meeting on December 5, celebrating the departure from the island of former I.G.P. Hector Dowbiggin. In early 1937, he addressed gatherings at the South Indian Maruthavar Sangam and the Ceylon Muslim League hall, and attended a meeting of the All-Ceylon Barbers’ Association—all of which were duly noted by the C.I.D.

Nawalapitiya

Meanwhile, Bracegirdle went to meet Kothandarama Natesa Iyer, who, together with Desigar Ramanujam and others, founded what would later become the Ceylon Workers’ Congress, the biggest trade union in Sri Lanka. Iyer offered Bracegirdle the post of union organiser in Hatton or Nawalapitiya. However, he could not find accommodation.

On March 28, 1937, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay of the Congress Socialist Party of India arrived in Colombo to give a series of speeches. Bracegirdle went down to the docks to greet her, and accompanied her to meetings at the Colombo Town Hall, Panadura, Galle Face Green, Nuwara Eliya, and Kandy.

Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay’s meeting at Galle Face. Image courtesy Samasamajaya

On April 3, he accompanied her to a meeting at Nawalapitiya. After her speech, N. M. Perera introduced him to the crowd of 2,000, mainly estate workers:

“Comrades, you know I have an announcement to make. You know we have amongst us a white comrade. He is the soul of our movement. He sheds tears for you. We are in the very happy position of having this presence here this evening. He has generously consented to address you. I call upon Comrade Bracegirdle to address you.”

At this, Bracegirdle mounted the platform. The workers greeted him with applause and cries of “Sami, Sami” (Lord, Lord), which continued to punctuate every sentence of his speech. Calling the white planters “parasites”, who “suck your blood”, he detailed how the workers’ rights under the law were being violated by them, for profit.

“Do not fear the white man”, he said, “Come to us, we will help you. We have two State Councillors in our party. Here they are (points to N. M. Perera and Philip Gunawardena). They will expose these planters in the council. There we have two lawyers in our party. They will appear free in your cases. The planters cannot act illegally. The courts will punish them. The courts will punish them. The courts will fine them. The courts will imprison them.”

Mudaliyar Arumugam of the C.I.D., who kept the meeting under surveillance, reported that the labourers remarked that “Mr. Bracegirdle has correctly said that they should not allow planters to break labour laws and must in future not take things lying down.”

In Hiding

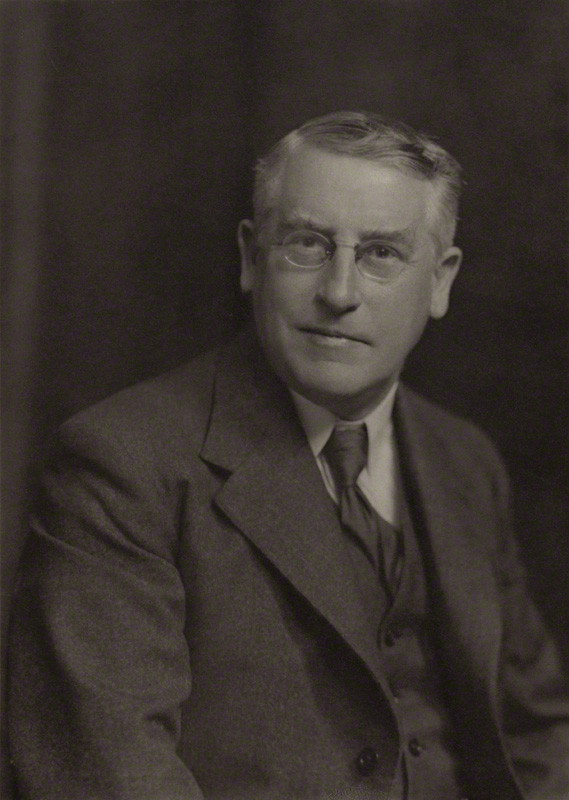

Significantly, this speech, which impacted on the planters’ illegal exploitation of their workers, rather than all of Bracegirdle’s previous political activities, galvanised the C.I.D. into recommending his deportation. This was endorsed by I.G.P. Banks. On April 20, Governor Stubbs, holidaying in Nuwara Eliya, duly signed an order to deport Bracegirdle. Notice was served on Bracegirdle on April 22, giving him 48 hours to pack his bag and board the steamer Mooltan, on which passage had been booked for him to Fremantle.

I.G.P. Banks. Image courtesy Sri Lanka Police

“The Samasamaja Party took a decision,” wrote Philip Gunawardena’s brother Robert in his memoirs, “especially to act against this arbitrary order and immediately to hide Bracegirdle. The Party entrusted to Reggie Senanayake, an enthusiastic party activist, and myself the task of hiding Bracegirdle.”

For three days, they hid Bracegirdle at a house called “Pretoria” in Colombo. Then they drove him to Lunugala, in Uva to a place which had been found for him. Arriving at 4:00 a.m., they discovered that it was not suitable, and decided to take him back to Relugas, where a cave existed which he could hide in. Driving all day, buying provisions at Nuwara Eliya on the way, thither they took Bracegirdle, disguised as a woman. They left him at Relugas, promising to return in a week.“Taking a few tins of food and some tea and a billycan,” wrote Bracegirdle later, “I looked after myself for about eight days. The most difficult part was remembering to cut notches in a stick to mark each day.”

After a week had passed, Robert Gunawardena, Reggie Senanayake and three others, with a pistol for protection, went up to Relugas in two cars. At about midnight they arrived and shone torches into the jungle as a pre-arranged signal.

Earlier, Bracegirdle made his way down towards the meeting place, but found a man collecting wood in his way. He had to swing on a liana down a thirty-foot cliff face to get to the rendezvous.

Stamp issued to commemorate Robert Gunawardena in 2004. Image courtesy Delcampe.net

Returning to Colombo, Robert Gunawardena left Bracegirdle at a “safe house” at Kosgashandiya, Grandpass. However, two days later they felt it was not safe, so he took him to a house in Weka estate in Koratota, Kaduwela (now the Sanctuary Lodge). Here he remained until May 5—whiling away the time by giving an interview to a journalist of the Ceylon Daily News.

Where Is Bracegirdle?

While Bracegirdle was in hiding, the L.S.S.P. put all of its meagre resources to work, drumming up support for quashing the deportation order. It held rallies, at which the slogan “Banks, Out” was popularised, and circulated leaflets asking “Where is Bracegirdle?”. That year, the May Day procession was replete with placards reading “We want Bracegirdle – Deport Stubbs”. The party announced that Bracegirdle would emerge from hiding at a rally on Galle Face Green on May 5.

Meanwhile, the upsurge of public sympathy for Bracegirdle put pressure on the “moderate” members of the State Council. They were disturbed by the fact that the deportation order had been made by-passing the Minister of Home Affairs, Don Baron Jayatilaka, technically the I.G.P.’s boss. On May 4 and 5, the deportation order was debated by the House, which passed a motion, censuring the Governor for acting contrary to the constitution, 34 to 7—the “Noes” including six “official” (nominated) members, the only elected member to vote against the motion being G. G. Ponnambalam. It was a portentous display of national solidarity against the colonial power.

Many of the “Ayes”, among them S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike, Susantha de Fonseka, R. S. Tennakoon, D. M. Rajapaksa, Siripala Samarakkody, George E. de Silva, A. E. Goonesinghe, Philip Gunawardena and N. M. Perera, went straight from the State Council to the rally on Galle Face Green. Among the other speakers were Mrs. Natesa Iyer (who spoke and sang in Tamil), Handy Perimbanayagam (formerly of the now defunct Jaffna Youth Congress), Vernon Gunasekera, Leslie Goonewardena, and Colvin R. de Silva, who presided. The Green was filled with a then-unprecedented crowd of 50,000.

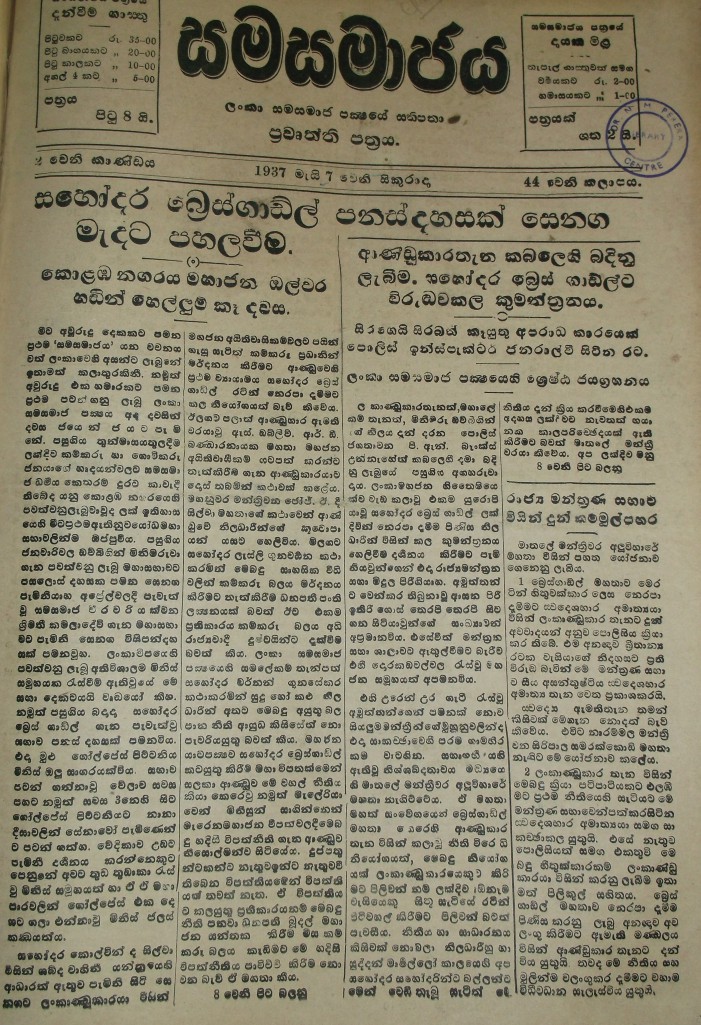

The Samasamajaya report of Bracegirdle’s spectacular appearance at Galle Face.

In the meantime, Robert Gunawardena drove to Weka estate, where he got Bracegirdle to lie down on the rear seat, and drove back to Galle Face. He drove through the police cordon, and stopped the car about 150 metres from the platform to let Bracegirdle out. The latter bounded to the platform and climbed on. He was greeted with roars of “Comrade Bracegirdle, Comrade Bracegirdle”. Garbed strikingly, in a white suit with a blood-red shirt and tie to match, he began speaking.

“I had to have three interpreters,” he recalled later, “Tamil, Sinhalese and Malayalam. If only one part of the audience laughed at a joke, I had to give the interpreters another chance to translate it.”

According to the Independent, May 6, he said:

“I have been called an ‘undesirable’—This was because I took the side of the oppressed masses of Ceylon… I exposed the everyday tricks of my countrymen. I showed how they violated the Indian Labourers’ Wages ordinance,”—which was the law of the land and so it was considered ‘undesirable,’ that I should show their own undesirable ways… Comrades, I took your side because I believe that liberty and justice cannot be decided by colour. You my friends have dark skins, but you have white hearts while my countrymen here have white skins but their hearts are filled with black treachery of such a nature that even a plague rat would disdain to inhabit their ‘hearts’.”

Deportation Quashed

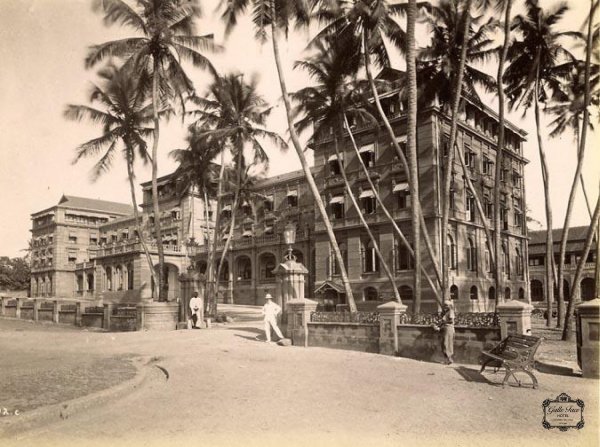

The Police did not dare to arrest him in the midst of this crowd. That evening Bracegirdle cocked a snook at them by dining openly at the Grand Oriental Hotel in the Fort. However, two days later, at Vernon Gunasekera’s house, the Police took him into custody, intending to put him on board the steamer Chitral. However, the L.S.S.P. applied for a writ of habeas corpus, which was granted by the Chief Justice, Sidney Solomon Abrahams.

H. V. Perera, a brilliant civil lawyer, offered his services free. A panel of three judges, including Abrahams, reviewed his application and on May 18 issued its judgement, deciding that the Governor’s deportation order was illegal. Bracegirdle was free. It was an utter humiliation for the colonial government and for the Planter Raj.

The case received wide publicity throughout the British Empire. S. A. Wickremasinghe of the L.S.S.P., then in London, organised a protest meeting chaired by Reginald Sorenson, Labour Party MP for Leyton West. In the British Parliament on June 9, Sorenson asked the Colonial Secretary, William Ormsby-Gore, whether he had taken any action respecting the action of the Governor in making the illegal deportation order. Ormsby-Gore avoided answering. However, the writing was on the wall. Stubbs stepped down on June 30. His replacement, Andrew Caldecott, only took office on October 16.

Governor R.E. Stubbs. Image courtesy National Portrait Gallery]

Meanwhile, the Board of Ministers recommended that I.G.P. Banks be removed, since he lied when he said that he had informed Minister of Home Affairs D.B. Jayatilaka about the proceedings against Bracegirdle. Subsequently, Caldecott appointed a commission of inquiry headed by Justice Abrahams. A year later, the commission published its report, exonerating Banks and the government bureaucrats, and finding fault with Jayatilaka.

The State Council immediately passed a motion of confidence in Jayatilaka. Two weeks later, on November 22, 1938, Philip Gunawardena moved to condemn the commission report as a whitewash aimed at entrenching the position of the white bureaucracy against the popularly-elected representatives of the people. He emphasised that the commission had not been appointed at the request of the House, but had been the Governor’s baby. He also made it clear that the deportation order was the result of a conspiracy of white bureaucrats.

The debate went on for five days, during which N. M. Perera took the opportunity to point out, as Natesa Iyer had during the earlier debate on the deportation order, that the white bureaucracy was essentially protecting the interests of the Planter Raj. However, the motion was defeated 43 to 5—only Natesa Iyer, D. P. Jayasuriya, D. M. Rajapaksa and the two L.S.S.P. members voting for it.

The native elite had too much involvement with the colonial system to critique it. They were more interested in seeing the back of the Bracegirdle controversy than in courting further clashes with the colonial power. Instead, the State Council passed a fairly tame rejection of the commission report, 34 to 14.

The Independence Struggle

However, the genie was out of the bottle. The Bracegirdle incident and the subsequent British imprisonment of the Samasamajists as a response to a strike wave in the estates, laid bare the essential truth of the colonial system and the Planter Raj—that it was intended to exploit the country for the benefit of the foreign overlords.

The scandal surrounding the Bracegirdle incident and the subsequent attempt at a whitewash caused such a groundswell of opinion that Governor Caldecott began the process of constitutional reform which led to the the Soulbury Constitution.

The imprisoned leaders of the L.S.S.P. escaped and fled to India, where they participated in the Quit India rebellion and agitated for independence for India, Burma, and Sri Lanka, recognising that regional freedom was a prerequisite for national freedom. Meanwhile, the party continued its agitation and strike action in Sri Lanka, led by Robert Gunawardena. The experience of hiding Bracegirdle proved invaluable in these mainly underground activities.

In May 1942, L.S.S.P.-influenced Sri Lankan gunners of the garrison of the Cocos Islands, mutinied, led by the charismatic Gratien Fernando. The mutiny failed, and Fernando, speaking defiantly to the end, and two other ringleaders were executed. Nevertheless, the British were so unnerved that no other Sri Lankan unit served in the front line thereafter.The next year, the Ceylon National Congress, the organisation of the native elite, voted for full independence. D. S. Senanayake, who by this time was committed to dominion status, resigned from the organisation. In November 1944, Susantha de Fonseka moved in the State Council that Sri Lanka be given dominion status. The next year, the State Council passed the Free Lanka Bill. There was still no commitment to full independence.

With the end of the Second World War, the L.S.S.P. leaders returned from India and immediately launched a strike wave aimed at getting the British out. At elections held in 1947, the Left gained 25 Parliamentary seats out of 95. With India independent, the British position in Sri Lanka was untenable, especially given the threat from the Left. In 1948 they granted the island dominion status, but kept intact their control over the armed forces and over air and naval bases. It was only after 1956, when the Mahajana Eksath Peramuna government, which included Philip Gunawardena as a co-leader, took office, that indigenisation of the armed forces command took place and the air and naval bases were taken over.

On May 22, 1972, a few days past the 35th anniversary of the Bracegirdle incident, the country cut its final ties to the British Empire by becoming a republic, the new constitution being written by Colvin R. de Silva, who had first introduced Bracegirdle to the public. The Planter Raj came to an end with the nationalisation of foreign-owned estates and agency houses, which had not been possible under the previous constitution. The country gained, finally, the political independence which Philip Gunawardena had set out to achieve four decades previously. Sadly, he did not live to see it, passing away two months before.

Epilogue

Following his release, Bracegirdle worked at the L.S.S.P. press. In October he decided to go to Britain, to be united with Mary Elizabeth Vinden, whose short holiday in that country had turned out to be a permanent domicile there. He was seen off at the docks by N. M. Perera, Selina Perera, Vernon Gunasekera and Ven. Udakandawala Siri Saranankara Thero (later Chairman of the Communist Party). He married Mary Elizabeth Vinden in 1939

In November 1938, the Sydney Workers’ Weekly reported that the reactionary Lyons government in Australia had cancelled Bracegirdle’s passport, effectively serving him with a deportation order from Australia! He was not to return to Australia, except on a brief visit in 1988 to his brother Simon.

He joined Philip Gunawardena’s old organisation, the League Against Imperialism, but was sidelined by Krishna Menon because he had by then joined the Communist Party of Great Britain, of which he remained a member until its dissolution. He became a lecturer in Engineering and at one time worked for the flying doctor service in Zimbabwe. He had three daughters and a son. This writer had the privilege of driving his daughter, Gillian, to Relugas Estate, a few years ago. Mary Elizabeth passed away in 1980. Bracegirdle followed her on June 22, 1999.

Bracegirdle’s granddaughters visit Relugas estate, 2010. Image courtesy writer

Bracegirdle’s biggest legacy is undoubtedly his contribution to Sri Lanka’s independence struggle. By his actions, he drove a rift between the British bureaucracy and the native elite and caused the turmoil which led to the process of constitutional change. More importantly, he showed the ordinary people of Sri Lanka the true nature of the colonial government as a mere cover for the exploitative Planter Raj. Ripping off the paternalist veneer, he doomed British overlordship of the island to destruction.