From murder to stealing mudcrab pots, Sri Lankan-origin law-breakers have been active in Australia for a long time. Some were exiled there as punishment, and became model citizens. Others were incorrigible reprobates.

Sri Lankans have been part of Australian history since the early 19th century. However, with the “White Australia” policy in place from 1901 to 1973, only those who could prove more than 50% White ancestry were allowed to migrate. Non-white Australians, including under-50% white Sri Lankans, tended to remain in obscurity.

Since they were “under the radar”, most of the very few glimpses we get of them tend to be of the ones who showed up in criminal cases – which might give observers a somewhat jaundiced view of the islanders. Not all of them were convicted, nor were the convicts always wrong-doers.

Transported

Like the first British settlers “Down Under”, the first Sri Lankans migrants were convicts “transported” to Botany Bay, the settlement which became Sydney. “Transportation” – exiling to a penal colony – was considered worse than a death sentence. Which it sometimes was.

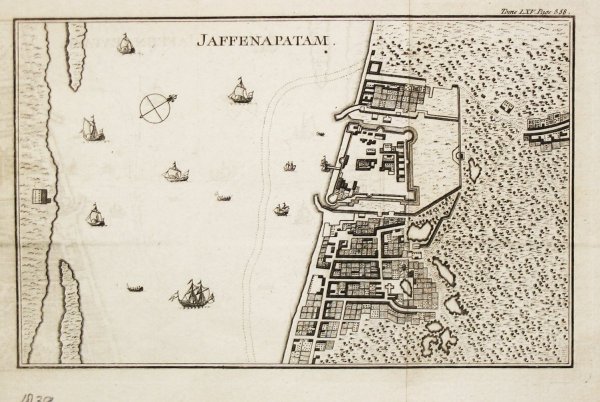

On October 13, 1808, Governor Thomas Maitland, by his official diary (now at the Sri Lanka National Archives), wrote to John D’Oyly to take “the bodies of Sanderadorege Jeronimis de Silva Liyenerale and Andries Fernando commonly called Anjo Sinjo”, who had been sentenced to transportation to Botany Bay, and deliver them to Captain John Cameron, commanding the East India Company ship Jane, Duchess of Gordon.We do know that the Jane, Duchess of Gordon proceeded to Kolkata and thence to Chennai, and we can only hope that the prisoners disembarked in India. The ship returned to Colombo and Galle, but disappeared in a gale off Mauritius, along with four other vessels, including Lady Jane Dundas. General Hay Macdowall, former Commander-in-Chief, Ceylon, who drowned, had taken over the cabin booked by puisne judge Alexander Johnston, who had therefore to board the Earl St Vincent, and so survived, to become Chief Justice of Ceylon.

“East Indiamen in a gale”, by Charles Brooking. Image courtesy wikimedia.org

In 2002, Glennys Ferguson published “The first Ceylonese family in Australia”, in The Ceylankan, the magazine of the Ceylon Society of Australia, with details of her ancestor of six generations, a Malay named Odeen, his “Cingalese” wife, Eva, and their offspring. It is generally accepted that they were the first Sri Lankans in Australia. According to her, Odeen, 40, formerly a Drum Major in the Malay Regiment, found himself convicted at a court-martial held in Colombo, on May 4, 1815, for desertion, and sentenced to be hanged – commuted to transportation to New South Wales.

Pioneers

According to Paul Thomas, who researched his background thoroughly, Odeen (or Oodeen ‒ probably Ud-Din) served in the British army during the Kandyan War of 1803, deserted to King Sri Wickrama Rajasinghe and fought on his side. In the Kandyan War of 1815, Odeen was captured by General Brownrigg’s troops at Gannoruwa. in 1815, Odeen, taken captive, found himself convicted of desertion and condemned to transportation to the British penal colony at Botany Bay.

In 1816, Odeen, Eva, and their children arrived in Sydney aboard the Kangaroo. Odeen found employment as a night watchman on the docks, and later as a constable. In 1827, he was sent north to the “Top End”, to serve as an interpreter between the colonists and Indonesian fishers from Makassar. Returning to Sydney, he worked as an unofficial court interpreter for Lascar sailors and, since he possessed the only Holy Quran in the colony, swore in Muslims. He also became known as a “priest”. He died in the Sydney suburb of Wolloomoolo in 1860, aged 87.

View of Raffles Bay, where Odeen served as interpreter. Image courtesy wikimedia.org

In 1838, Daniel Detlov von Ranzow, 17, was transported to Botany Bay from Penang, for attempted murder in Mumbai. While his parents, Mannar-born Lodewijk Carel, Count von Ranzow, Resident (1822-6) of the Sumatran province of Riau, and Johanna Elizabeth Cramer, had European genealogies, he looked non-European – yellow skin, dark hair, and dark chestnut eyes. A former ship’s captain’s mate (they recruited them very young then) he had already been convicted, together with Lodewijk Carel, for the attempted murder of a Malacca magistrate, two years before. Paroled in 1841, he received a conditional pardon, according to the New South Wales Government Gazette of January 9, 1849. While born in Riau, he could be claimed a Sri Lankan, on account of his parentage.

Black Sam

On January 5, 1843, on a sheep station near Adelaide, a Sri Lankan cut and stabbed a man named John Quartermain (or Quarterman or Gaurderman). The Adelaide Southern Australian, of February 7, 1843 referred to him as “Samuel Davis de Lozay, a black native of Ceylon, better known as Black Sam”, the rest of the Press calling him, variously, Philip de Lozay, Samuel Davy DeSozay, Samuel De Souzay or Da Souza – the Australians apparently still retained the English inability to pronounce foreign names. It sounds like they found it difficult to get the hang of “du Bois de Lassosay”.

The 30-year-old accused may have been a common-law descendant of Guillaume Joachim Comte du Bois de Lassausay, who came out to Sri Lanka with the Luxembourg Regiment, in the service of the VOC. The Comte appears to have adopted the spelling “de Lassosay” and left several legitimate descendants in Sri Lanka, including Leembruggens, Speldewindes, and Kriekenbeeks.

Quartermain and four or five others, reported the Southern Australian, “had been beating Sam, throwing dust in his face, spitting in his tea, and otherwise annoying him by calling him a thief, and upbraiding him with being a black rascal without a God.” In retaliation, he had stabbed Quartermain in five places. Hauled up before the magistrate two weeks later, de Lozay “did not deny the fact, but pleaded great irritation”.

With de Lozay committed to trial before the South Australia Supreme Court, the Southern Australian of March 10, 1843 reported that neither prosecutor nor witnesses appeared. Because of the continued absence of the prosecutor, de Lozay got bail on his own cognisance, but had been frightened out of his wits. The case of two Aboriginal people Nultia and Moullia, had just been heard and they had been condemned to hanging. Said the South Australian Register of March 29 about de Lozay:

“The poor fellow, black as he was, almost changed colour, upon being called up immediately after sentence of death had been pronounced upon Nultia and Moullia, but he thanked the Judge very politely for his indulgence, and promised to be in attendance whenever he might be required.”

The case was taken up again on July 18, but again Quarterman failed to appear. “Should not the prosecutor now appear,” reported the Southern Australian of July 21, “some means must be employed in order to his being taken.” None appears to have been utilised, since we hear nothing more of the case.

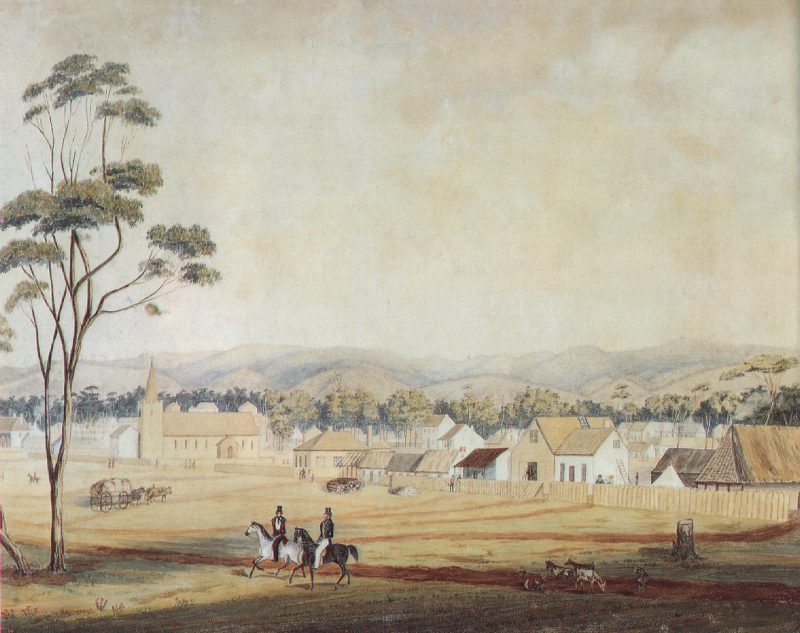

Adelaide in 1839. Image courtesy wikimedia.org

Amadoris and Saranealis

The pearling industry on Thursday Island, off the north tip of Queensland, attracted many Sri Lankan immigrants, mainly jewellers from Galle. On July 17, 1900 Semba Kootie Amadoris and Peter Kuruwaru went in search of a third Sri Lankan, Yahatowgoda Baddallegay Saranealis, a jeweller, intending apparently to shoot him. Saranealis had sold his jewellery shop to Amadoris, but re-started a new jewellery shop later. This may have been the object of contention between the two.

The North Queensland Register of July 23 reported that the pair assaulted a man named Soopaya, and his wife, because they did not tell him the whereabouts of Saranealis. A Chennai Muslim called Bacca came to the aid of the couple, so either Amadoris or Kuruwaru shot him – later, each accused the other.

Bacca made a dying deposition, in which he identified his assailants. The case was heard on October 5, in Cooktown. The Maryborough Chronicle of October 6 reported that the men were found guilty of manslaughter and sentenced to seven years’ penal servitude. They appealed to the Supreme Court of Queensland, on the basis that the dying declaration could not be taken as evidence, because the declarant did not know surely that he was dying and because he was not particularly religious, being a Muslim. The appeal was denied.

Amadoris seems to have been nothing if not single-minded. The Rockhampton Morning Bulletin of October 19, 1906 reported that, on Thursday Island two days previously, Amadoris, having done his time, attempted to stab Saranealis, but was prevented from doing so.

Saranealis House, founded by Y.B. Saranealis. Image courtesy auroracloud.com.au

“Cingalese Deen to Die”

A fracas broke out between two Sri Lankans, Charles Deen and Peter Dina, in Innisfail, about 90 km south of Cairns, northern Queensland, on February 4, 1913. The Cairns Post of February 8 reported that Deen had stabbed Dina with “an ordinary butcher’s knife, which penetrated the lung and went almost to the spine.” He was remanded to trial at the Townsville circuit court, according to the Brisbane Courier of February 13. The newspaper reported on March 5 that he had pleaded guilty the previous day, and on the next, that he had been sentenced to death.

“Cingalese Deen to Die” headlined the Brisbane Courier’s report on April 18 of the Governor in Council’s denial of his appeal. While press coverage of his trial was brief in the extreme, his execution on May 5 at the Boggo Road Prison in Townsville received wide and deep coverage. The Brisbane Courier of May 6 said he wore “a faded blue shirt and white trousers somewhat soiled and tied around the waist with a piece of tape for a belt… a pair of dark woollen socks and a pair of old rubber shoes without laces.”

“He walked with a firm step,” it continued, “and was led unresistingly to the centre of the

trap doors. Seeing the group of officials and Pressmen below him he said, in a low voice, a little shaky, but perfectly self possessed: “Good-bye, gentlemen; I am going now.” His last words were that he had nothing to say.

Row at the Cingalese Club

By the early 20th century, there were so many Sri Lankans in Woolloomooloo that there was even a “Cingalese Club” there, at 18 Judge Street (now bisected by a railway line), not far from where Odeen died. The building was demolished in the ’20s or ’30s.

The Sydney Evening News of February 11, 1919, reported somewhat excitedly, “a shooting affray, in which three Cingalese and one Arab were concerned,” the previous evening, “the outcome of a quarrel at the Cingalese Club.” The true facts came out during the inquest, and were published in the Sydney Evening News and Sun of May 15, 1919. It appears that Handy Amadoris, 49, was preparing to have dinner at the Cingalese Club with his uncle Arles de Silva (the “Arab”), a cook who lived there; Joseph Francis, a kitchenman; Thomas Dionis; and Joseph Bundar (Banda?). They got into an argument, and Dionis threw a plate of steaming rice over de Silva. Amadoris and Bundar tried to stop Dionis, a bad-tempered 25-year-old, who then assaulted Amadoris repeatedly, knocking him down. Amadoris picked up a carving knife, but Bundar took it away from him.

Amadoris fled the scene, got drunk, went to a pawn-broker, pawned his gold watch and, with the proceeds, bought a revolver and cartridges. He then went to 174 Duke Street, the house of William Perera. There, Dionis knocked him down with a shovel, cutting his ear so it bled. Amadoris then shot Dionis in the head and Bundar in the abdomen. Bundar survived but Dionis died from the wound.

The Sun of June 24 reported that Amadoris pleaded guilty to assault on Bundar and manslaughter of Dionis. The Judge sentenced him to 15 years, instead of life, because he was “a coloured man”. He did not live out his sentence ‒ he died of tuberculosis on February 4, 1921. The Newcastle Sun said that he had been moved from Goulburn Jail to Long Bay prison on January 19 on account of his lung trouble, and had to be taken to the Coast Hospital, where he died.

The Cingalese Club was probably the house in the middle. Image courtesy Sydney City Archives

Mudcrabs

In 2000, Allen Keith Appo, 66, of Bunderberg, was charged with possessing undersized and female mudcrabs. He claimed that, as an Aboriginal person, he could fish without restriction. However, government legal officers found that his heritage was “purely Sri Lankan”. Five years earlier, another Appo had been found guilty of the same offence. In their defence, many of the hundreds of Sri Lankan migrants to Queensland in the 1880s were absorbed into the Aboriginal population, and several Appos, such as Bradley and his elder brother Lyall, have gained fame as Aboriginal sportspeople.

The Appos are representative of the generations of Sri Lankan immigrants from before the “White Australia” policy, many of whom have forgotten their origins. How many thousands of Sri Lankan “boat people” made their way to the Southern Continent over the years, we do not know. Most would have lived within the law: it was just a few who were caught for actual or alleged crimes. The very fact of their “Otherness” resulted in greater than expected publicity. However, this very publicity has preserved a record of the lives of early Sri Lankan immigrants which would not otherwise be available.