In 1938, Heinrich Himmler, one of the leading members of Germany’s Nazi Party and a key architect of the Holocaust, appointed a five-member team to go to Tibet, to search for the origins of the ‘Aryan race’.

Their mission, however, began in Sri Lanka — then Ceylon — where they planned to spend a few weeks studying the population of Ceylon and its potential Aryan heritage.

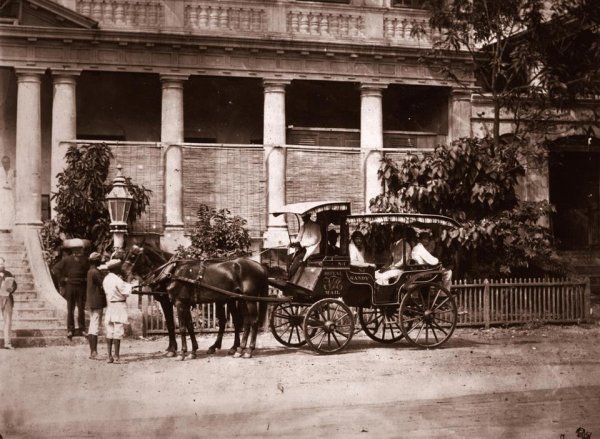

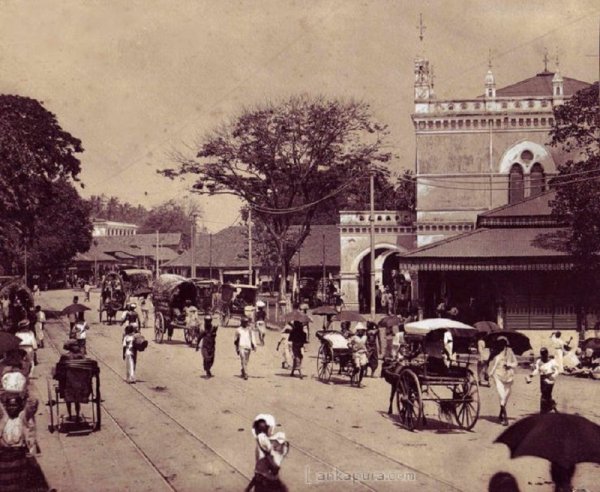

And so, a little over a year before the second World War began, a group of Germans landed in Colombo. The ship carrying the five Germans docked at Colombo in May 1938. They had planned to travel to Madras (now Chennai) and then to Calcutta (now Kolkata) and finally, through Sikkim to Lhasa, Tibet’s capital city, after their brief stay in Ceylon.

But the trip would be cut short by the British occupiers in India.

The Team

Two participants of the expedition stood out the most: Ernst Schäfer (28) — the lead explorer, directly appointed and funded by Himmler himself. He was a zoologist who had been to the Indo-China-Tibet border twice previously.

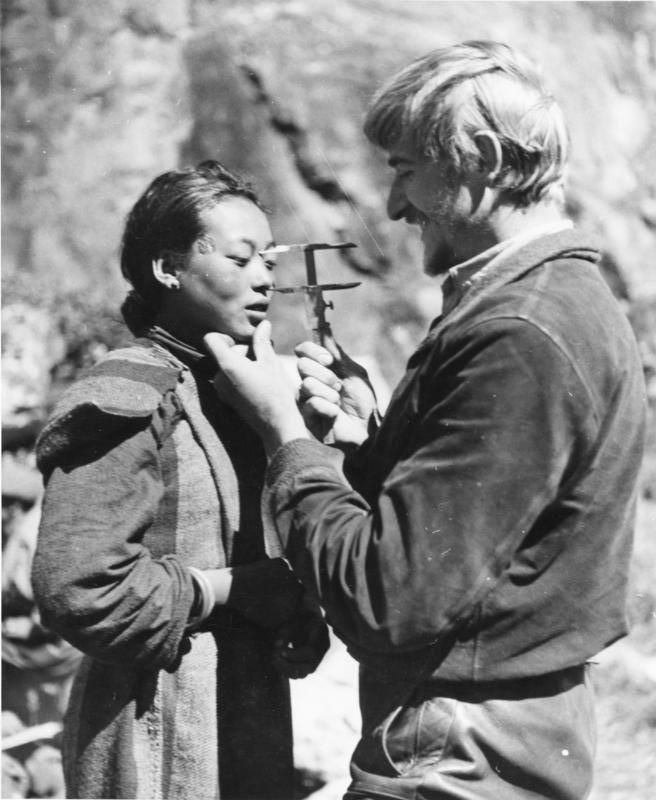

The other was Bruno Beger, a young anthropologist and an expert in racial sciences. Author Vaibhav Purandare in his book Hitler And India: The Untold Story of his Hatred for the Country and its People wrote that inTibet, Beger would take measurements of the skulls and facial details of Tibetans and make face masks, “to collect material about the proportions, origins, significance and development of the Nordic race in this region”.

The other members were geologist Karl Wienert (24), technical lead Edmund Greer (24) and filmmaker and entomologist Ernst Krause (38).

Hitler And The Origins Of The Aryan Race

Germany’s fascination with the concept of the Aryan race dates back to at least a decade before the Tibet expedition.

The almost-obsession, according to historians, began with the translation of 4th century India’s greatest playwright Kalidasa’s Sakunthala into the German language in 1791, which was when a close relationship between Sanskrit and European languages was first observed. This was when the romanticised search for the original land of the Europeans began.

German orientalist Max Muller in his A History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature (1859) said, “Greece and India are indeed the two opposite poles in the historical development of the Aryan man.” In the same study, he went on to say, “Indians are our nearest intellectual relatives.”

This assumed common ancestry of an Indo-Germanic race, thus created the ‘Aryan myth’.

Adolf Hitler believed that Aryan entered North of India some 1,500 years ago, where he believed that they committed the ‘ultimate crime’ of mixing with the local ‘un-Aryan’ people, therefore losing features that had made them racially superior to all others.

Hitler was not the biggest fan of India. And no records show that he was ever interested in the small island of Ceylon just south of the peninsula. But others were; many, like Himmler, believed that the true origin of the ‘Master Race’ could be found in the South Asian subcontinent.

The German Who Loved Sinhala

Thanks to its close proximity to India, Ceylon, too, fell under the radar of German fascination.

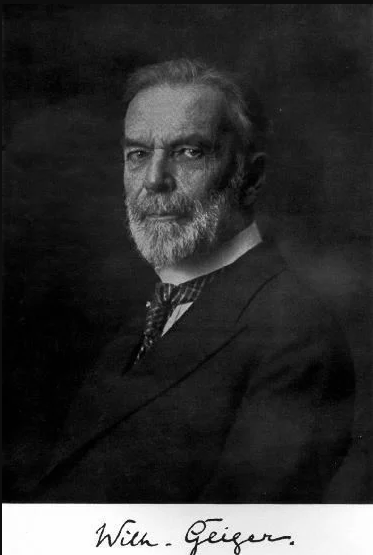

German orientalist Wilhelm Geiger, known for his extensive studies of Sri Lankan chronicles Mahavamsa and Culavamsa, was one of the first to study Sri Lanka’s connection to the Aryan race.

Professor of History, Sirima Kiribamune in her essay Geiger And The History of Sri Lanka notes that during Geiger’s two visits to Ceylon, he carried out studies on the Sinhala language.

In fact, in 1895, speaking to the Ceylon Independent on his arrival in Sri Lanka, Geiger said he wanted to study Sinhala for scientific purposes, in order to see if the language fell under the Aryan category. He also wanted to be a mediator between the scholars of Europe and Sri Lanka.

Kiribamune observes: “Judging from Geiger’s activities in Sri Lanka during this visit and two subsequent visits in 1925and 1931 respectively, this last reason seems to have been the foremost motivating factor compelling him towards a close personal link with the island […] Geiger’s interest in Sri Lanka came at an opportune moment. During his first two visits to the island in 1895 and 1925 respectively, Geiger walked into the thick of the Buddhist revivalist movement which arose as a challenge to British colonial policy and Christian missionary activity.”

A Failed Expedition

Geiger’s work would influence the Tibet-bound voyage and their arrival in Colombo.

Before the group left for India, the scientists led by Schäfer were planning to study the Ceylonese and make connections for future exploits. But their intentions of travelling out of Colombo, were quickly shot down by the British officials who were still in control.

Due to the strict control, the Germans could not leave Colombo and their visit to Ceylon was cut short.

The team eventually reached India and then started their journey to Sikkim in June 1938. After six months, they finally reached Tibet during the winter. According to author Vaibhav Purandare, the team entered Tibet, with swastika flags tied to their mules and baggage.

And yet the search operation soon began to feel the pressures of the growing war in Europe. By August 1939, the expedition could no longer deny the war in the region and its spillover effects in Asia.

By the end of the operation, Beger had measured the “skulls and features of 376 Tibetans, taken 2,000 photographs, made casts of heads, faces, hands and ears of 17 people” and collected the finger and hand prints of another 350, Purandare noted.

He had also gathered 2,000 “ethnographic artefacts”, and another member of the contingent had taken 18,000 metres of black-and-white film and 40,000 photographs.

Upon their return to Germany, the team was greeted by Himmler who congratulated Schäfer and company. Because of the war, Schäfer’s writings about the trip were not published until 1950, under the title Festival of the White Gauze Scarves: A research expedition through Tibet to Lhasa, the holy city of the god realm.

His travel journal would go on to be printed in 1998 with only 50 copies of it existing as of today. But the massive amounts of “scientific results” — artefacts and material they collected from Tibet — were lost or destroyed during the war. And no one has bothered to trace the shame of the Nazi past.