Travelling along the Colombo-Kandy road, you may have heard stories of bandits from days of old. Narrated in awed tones, the storyteller would have pointed to a monolithic hill—Utuwankanda—in the distance, and told you of Saradiel, the highway-man who robbed coaches at gunpoint and then distributed his stolen goods among the poor, before disappearing into his hide-out in the forest surrounding Utuwankanda.

A Pocketful Of Trouble

Born on 25 March 1832 to Adissi Appu and Pichohami in Utuwankanda, Saradiel was the eldest of five children. He received his primary education at a temple in Illukgoda. Stories of his notoriety stem from there, when he attacked a boy from a more influential family. The boy and his friends were said to be bullies and had picked on Saradiel and poorer village children constantly, which eventually provoked a reaction.

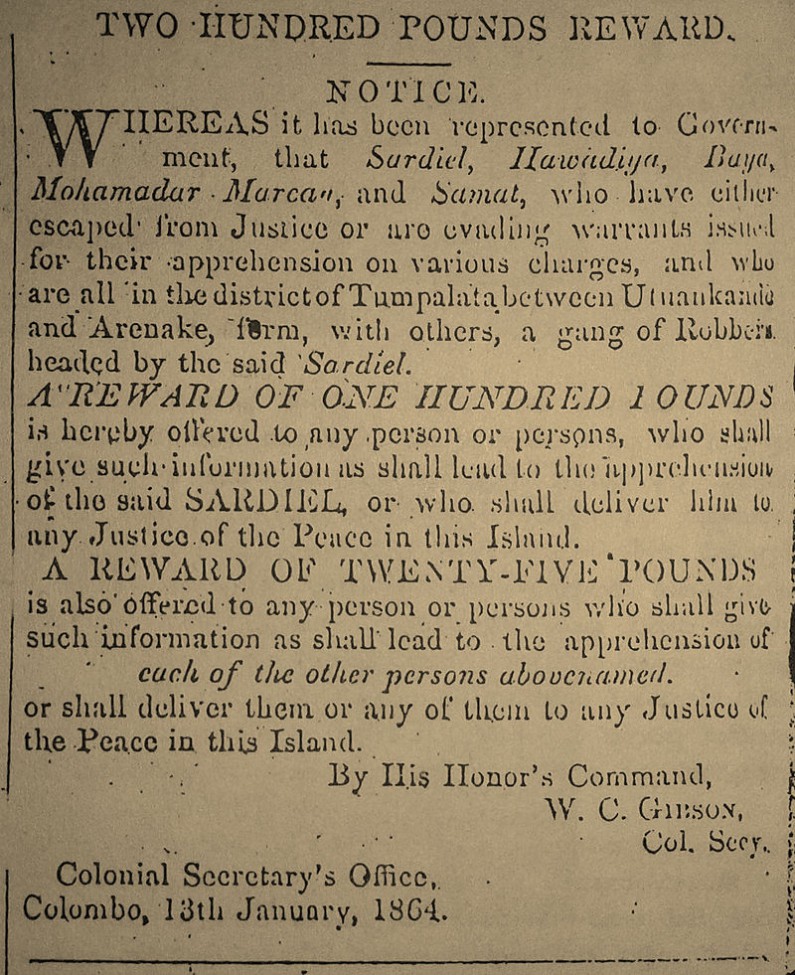

Afraid of the consequences of his actions, and with the police on his heels for assault, Saradiel fled towards Colombo. In the then-capital city, he managed to find work as a domestic to an official at the army barracks. While working there, he learned how to use firearms and weapons, a skill he utilised quite frequently later in life. His stint at the army didn’t last long though. Saradiel robbed his employer, apparently of some silver utensils, and then fled the barracks. Upon returning to Utuwankanda, he got together with a group of friends and spearheaded a gang of highwaymen who became the bane of colonialists and wealthy merchants on the island. Their robberies targeted wealthy coaches traversing the Colombo-Kandy road, and officials who served the British, more often than not at gunpoint. His exploits became so well known that warrants were issued for his arrest, along with a reward for the capture of the gang, and additional police reinforcements were soon deployed not just to Utuwankanda, but to the surrounding villages as well.

Saradiel and his kalliya soon became among the most wanted people in the country.

A Life Of Crime And Kindness

Arrest warrant offering 200 pounds as a reward. Image courtesy Wikipedia.

Despite his turbulent nature and affinity to get into trouble, Saradiel was loved among his village community because he never stole or took anything from them. The bullying he faced in school instilled antagonism towards the wealthier and more powerful segments of society, and he sought to balance this out by redistributing their wealth among his own villagers. There are legends of how he returned cash he borrowed from locals. One such story is how he borrowed money from an old lady he passed on the road. It turned out that she was taking it for her daughter’s wedding, but parted with it willingly when Saradiel asked for it. The bandit was allegedly an avid gambler and wanted the money to fuel his habit. The next day, he returned the cash in double, as he had made enough winnings to tide him over. There are numerous versions of this story, ranging from how he stole precise amounts of cash (and not a penny more) from colonialists to pay off gambling debts he owed to the villagers.

Likewise, he never lived a wealthy life despite all the robberies he committed. Local lore has it that he remained poor because he continued distributing his ill-gotten wealth among the poor, earning himself the love, respect, and protection of the villagers. As he and his gang of bandits became increasingly more notorious, his felony count mounted over a 100 and he was branded a wanted man and traitor to the Queen. A 100-pound reward was offered for his capture and 20 pounds more for each of his henchmen.

The Hideout At Utuwankanda, Betrayal, And The End

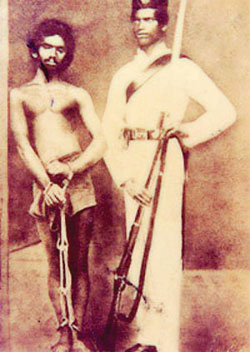

Saradiel, shortly after being captured in 1864. Image courtesy Wikipedia.

In July 1862, he was 27 years old. This was when he was first arrested for stabbing a man. Taken to the Hulftsdorp Courts for trial, he was finally imprisoned but managed to stage an escape in November, whereupon he returned to his hideout in the mountains.

Saradiel’s crimes weren’t committed alone: his faithful bandits included his best friend Mammale Marikkar, and several others known as Bawa, Samath, Hawadiya, Kirihonda, and Sirimale. He was arrested several times but managed to escape thanks to his friends, and often went into hiding at Utuwankanda. The mountain provided a bird’s eye view of the surrounding areas, from where the gang was able to see coaches and carriages plying the Colombo-Kandy road, and plan their next moves.

By March 1864, his luck was fast running out. Police from Kegalle, Mawanella, and Kurunegala were strengthening their forces against him. Saradiel’s crimes increased, as did the bounty for his capture or death. Eventually, Sirimale defected and worked with the police to orchestrate Saradiel’s capture. Saradiel was unaware of Sirimale’s act, even though Marikkar allegedly kept pointing out that Saradiel’s trust in Sirimale was unwarranted.

On the 21st of March, Saradiel and Marikkar were hiding at a safe-house suggested by Sirimale. The latter then tipped the police, and the house was surrounded by armed law enforcement officials soon after. A shoot-out followed, and a police constable by the name of Tuan Sabhan was killed in action.

The two bandits were eventually captured and tried at the Kandy Assizes, where they were found guilty and sentenced to death. They were executed on 07 May, 1864.

Life Beyond Death

Mammale Marikkar was Saradiel’s closest friend. They were executed together. Image courtesy Wikipedia.

Constable Sabhan was the first policeman to die on duty in Sri Lanka. In honour of his service and all those who followed his footsteps, 21 May was declared as the Police Commemoration Day.

Saradiel is seen by many as an anti-colonial hero and vigilante who had his people’s best interests at heart. Currently, there’s a model village recreating the one Saradiel grew up in, at the foothill of Utuwankande. Unimaginatively called Saradiel Village, it consists of life-sized sculptures engaging in village life and tableaus of the bandit’s life.

Despite being a notorious gambler and bandit, the stories of his kindness towards the villagers far outlive the stories of the crimes he committed—and given that those crimes were against privileged people who were disliked by the village community, his exploits are retold with pride. Newspaper reports state that approximately 5000 people went to “witness” his execution, and many beseeched divine intervention on his behalf.

It must be noted that there is little to no academic or historical research available to verify or justify the stories surrounding him, with the existing studies focusing instead on the communal harmony between the Sinhalese and Muslims in that era (Saradiel and Marikkar were best friends, and Saradiel was also in a relationship with Marikkar’s sister). A degree of skepticism is, therefore, warranted when approaching Saradiel’s legacy.

While the bandit was most definitely a criminal in the eyes of the law, his reputation grew larger than life after his execution, achieving an almost mythical status.

Cover image: mdgunesena.com