In March 1896, in the San Francisco suburb of Oakland, the Sri Lankan Buddhist revivalist and missionary Hewavitarne (Anagarika) Dharmapala, on a lecture tour of the USA, met Countess Canavarro. Seeking spiritual sustenance, she struck him as determined and forceful. According to Tessa Bartholomeusz, four months after meeting her, Dharmapala proposed that she travel to Sri Lanka and establish an order of Buddhist “nuns”, and become full-time principal of the island’s first Buddhist girls’ high school, Sanghamitta, named for the first female Buddhist missionary to Sri Lanka.

On the evening of August 30, 1897, at the New Century Hall on New York’s Fifth Avenue, Dharmapala administered to the Countess Canavarro the five Buddhist precepts (pansil), making her the first female convert to Buddhism on American soil. Thus, she became the first in a new order of “Buddhist nuns” which Dharmapala wanted to create in Sri Lanka, some seven centuries after female ordination died out. She took on the enormously significant religious moniker “Sister Sanghamitta”, recalling the ancient missionary, as well as the school she intended to run.

According to Thomas A. Tweed, the Countess, by the very act of conversion, caused a huge stir. In the rigidly Christian atmosphere of fin de siecle America, adopting another religion simply was not done. Although almost forgotten in the USA, in her day, she made a considerable impact on the spread of Buddhism, Bahá’íism, Hinduism, and esoterica in general.

Her effect on Sri Lanka, despite her short stay of three years, has been much greater. Her school still exists as Sri Sanghamitta Balika Vidyalaya, Punchi Borella, an offshoot of the co-educational Mahabodhi vernacular school resurrected by Dharmapala at Foster Lane. Her imaginings of what a Buddhist nun should be have had their effect on the order of Dasa Sil Mathas, even their attire being based on her original design.

Sri Sangamitta Balika Vidyalaya today. Image courtesy sangamitta.com

Sanghamitta Convent

Sanghamitta Girls’ School had a short but chequered history. Founded by the Women’s Education Society in 1891, its first principal, an Australian woman called Kate Pickett, drowned. Louisa Roberts, a local teacher, acted as a stop-gap until Marie Musaeus Higgins, a German-American, arrived. In 1893, the latter broke away and started her own school, Musaeus College. Thereafter, Kate Pickett’s mother, Elise, served as school director, returning to Australia just before the Countess arrived.

Dharmapala and the Countess wanted to establish Sanghamitta on the lines of a Roman Catholic convent school, with Buddhist nuns teaching the girls. Accordingly, the school was relocated from its existing location, Tichbourne Hall, and moved to the same location as the ‘convent’—the Sanghamitta Upāsikārāmaya. Dharmapala and the Countess decided on Gunter House, a single-storey building set amidst a hectare of gardens in Darley Lane (now Foster Lane), which the Maha Bodhi Society bought for LKR 25,000 (LKR 30 million in today’s currency).

The convent, school, and an orphanage were soon up and running, large crowds attending the opening. There was no shortage of pupils for the school. The Countess, who styled herself as Mother Superior, came to be known by the children as Nona Amma (or Madam mother). Sister Dhammadinna (a Burgher woman called Sybil LaBrooy) managed the household, and several Sinhalese ‘nuns’ completed the staff.

In mid-1898, Catherine Shearer, a nurse from Boston’s Eliot Hospital, joined her, becoming ‘Head Sister’ Padmavatie. However, the two did not get along. The Countess expected Shearer to run things for her, while she busied herself with Mahabodhi Society work.

This friction between them betokened a deeper difference in attitudes. According to Bartholomeusz, the Countess considered Shearer “a dreamer”, but herself remained ignorant of the discipline expected from a Buddhist nun. Much against his will, she accompanied Dharmapala to Kolkata and appears, at some point, to have tried to seduce him. Finally, she removed herself from Gunther House and set up a convent on her own. This not only proved unsuccessful but also doomed the Sanghamitta Convent.

“Gunter House”, from The Open Court

Who Was Countess Canavarro?

As an infant, Miranda Maria Banta—born in 1849 in East Texas, accompanied her mother to California. At 17, she married post-master, insurance agent, and scalp-hunter Samuel Cleghorn Bates, having four children by him. Bartholomeusz thinks he may have been an abusive husband, leading her to leave him.

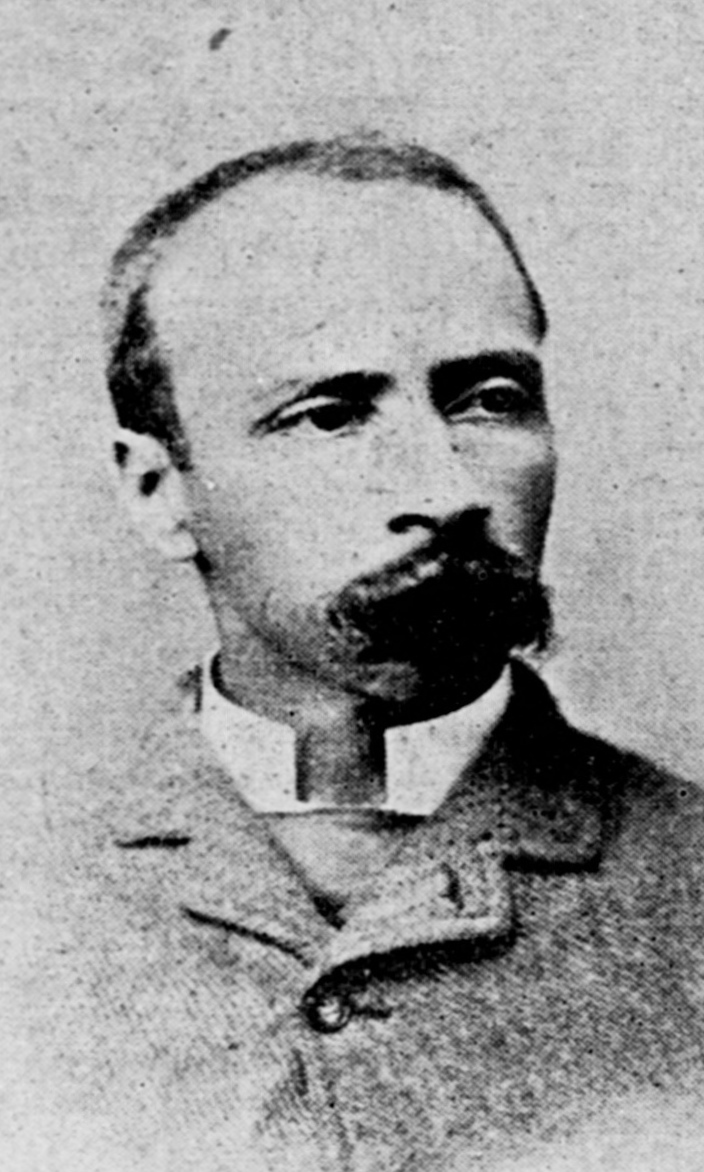

She probably met Lieutenant António de Souza Canavarro, scion of a noble family, on his way to become Portuguese consul-general in Hawai’i—then an independent country—in August 1882. By November the next year, she styled herself “Miranda A. de Souza Canavarro”.

António de Souza Canavarro. Image courtesy Wikimedia

A figure in West Coast high society, her conversion to Buddhism attracted considerable publicity.

Even the obscure Gazette Appeal of Marion County, Georgia, reported it:

This convert, whose purpose is to devote years of labor in the far east to uplift her sex, is the Countess M. De Canavarro, an American, formerly of San Francisco, who, to follow her chosen life surrenders, as the officiating priest announced, family, fortune, and title.

Years later, the whiff of scandal remained. The Greenfield, Iowa-based newspaper, Adair County Democrat claimed Dharmapala had hypnotised her and prevailed upon her to desert her family.

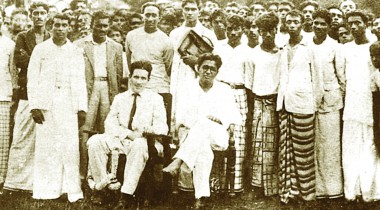

Countess Canavarro with teachers and students, from The Open Court

Companionate Marriage

In November 1900, after the Sanghamitta Convent debacle, the Countess returned to the USA, moving to the East Coast of the USA. She lectured on Buddhism and the Orient in general, several of her lectures being published.

Soon after, she entered a companionate marriage with a fellow Theosophist, Myron H. Phelps, a patent lawyer. The couple travelled to Sri Lanka posing as brother and sister. However, she continued describing herself as a Buddhist “nun”.

In December 1902, the Countess accompanied Phelps to Akka in Palestine, to meet ‘Abbás Effendí (`Abdu’l-Bahá ), the Bahá’í leader. The Countess interviewed ‘Abbás’ sister, Behiah Khanum, who provided the biographical material which went into Phelps’ book Life and teachings of Abbas Effendi. In late 1903, still bearing the name “Sister Sanghamitta”, she declared her acceptance of the Bahá’í faith.

Two years later, she and Phelps were to play host to the influential Hindu revivalist and moderniser Ponnambalam Ramanathan and his Australian secretary, Lillie Harrison, who would later become Ramanathan’s wife and take on the name Leelawathy. Ramanathan’s intellectual view of Hinduism attracted Phelps: by 1908, he would see himself as a Hindu.

The house in Akka, Palestine, where the Countess and Phelps met `Abdu’l-Bahá and Behiah Khanum. Image courtesy bahaihistoricalfacts.blogspot.com

Phelps left the Countess, journeying to India to join the independence movement. Almost bankrupt, she moved to a farm in Blackstone, Virginia, in a companionate marriage with Deuel Sperry, the longest-lasting of her relationships. She continued to lecture, but concentrated on writing: she produced several novels and the autobiographical “Insight into the Far East”.

In 1922 she moved back to Hawai’i, settling later in the Los Angeles suburb of Glendale, from where she would travel to the Ananda Ashrama, founded by the Swami Paramananda in nearby La Crescenta. For, in the last phase of her life, she adopted Vedanta Hinduism. She passed away in Glendale on July 25, 1933.

Countess Canavarro’s grave in Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale. Image courtesy findagrave.com

Legacy

Her legacy affected not only the future of Eastern religion in the United States of America, but also the development of Buddhism, which had already arrived in the USA along with the Chinese who flooded into California with the 1849 Gold Rush. The Countess represented a different type of Buddhist.

Even more profoundly, her example affected the way in which Sri Lankan society looked at women. Hitherto, crushed by Victorian values, the female gender were considered nothing more than sexual playthings or baby-making machines. According to Bartholomeusz,

The Countess and her “sisters,” by choosing to become world-renouncers, challenged the stereotype of the pious Buddhist woman as wife and mother; they helped to make renunciation a respectable choice for Buddhist women in Ceylon.

Despite the Buddha’s teaching enhancing the position of women, stressing the ability of women to achieve enlightenment and the existence of female arhants, later accretions to the canon made out that the feminine body proved a barrier to understanding the Dhamma. The Sri Lankan Buddhist tradition had, for seven centuries, lacked a female branch of the Sangha. This reinforced the idea of women being mentally inferior to their male counterparts, which became dogma.

Countess Canavarro, by resurrecting the image of the Buddhist woman seeking enlightenment, demonstrated the intellectual equality of genders and overthrew this perspective. Her action proved vital to the development of feminism in this island.