The great melding of literature and science comes in the form of science fiction; from interstellar worlds filled with exotic alien life forms, to travelling through time and grappling with vast social conflicts of genetically advanced ‘superhumans’, this literary genre has fueled the minds of many over the years.

While science fiction has, is, and will always be widely consumed in the West, in other parts of the world it has thus far only received somewhat of a subdued attention. In Sri Lanka, it is almost impossible to pinpoint when the first Sinhala language science fiction was published. Almost.

In The Beginning…

In a recent article, author Ruvinda Collure writes that the first use of scientific elements used in Sinhala language story, comes in the book of Five Hundred and Fifty Jathaka stories (පන්සිය පනස් ජාතක පොත). In its longest fable — the Ummagga jathaka — the Bodhisattva uses a switch to operate a door that opens to a tunnel system, which Collure compares to a modern-day electronic security system.

Even so, Collure does not believe that the jathaka story could have been the very first Sinhala iteration of science fiction, as the mentioned switch does not contribute to the rest of the storyline. Collure doesn’t believe that having elements of speculative fiction in them, allow stories to qualify as pure science or fantasy fiction.

The best possible example of the alternative was in the 1940s, when author Kumaratunga Munidasa published පුදුම තැන (A Strange Place). The short story revolves around a child living in a zero-gravity environment, narrating the bizarre occurrences that take place around him. The story was first published in a Sinhala magazine that has since gone out of publication.

Arrival Of Pulp Fiction

Between 1950 and the 1960s, Sinhala literature saw the arrival of pulp fiction which saw a massive influx of crime and detective stories. These books had colourful covers, and mostly racy content, and were cheap to publish and sold equally easily. However, only a handful of independent science fiction stories were written or even came into the limelight during this period.

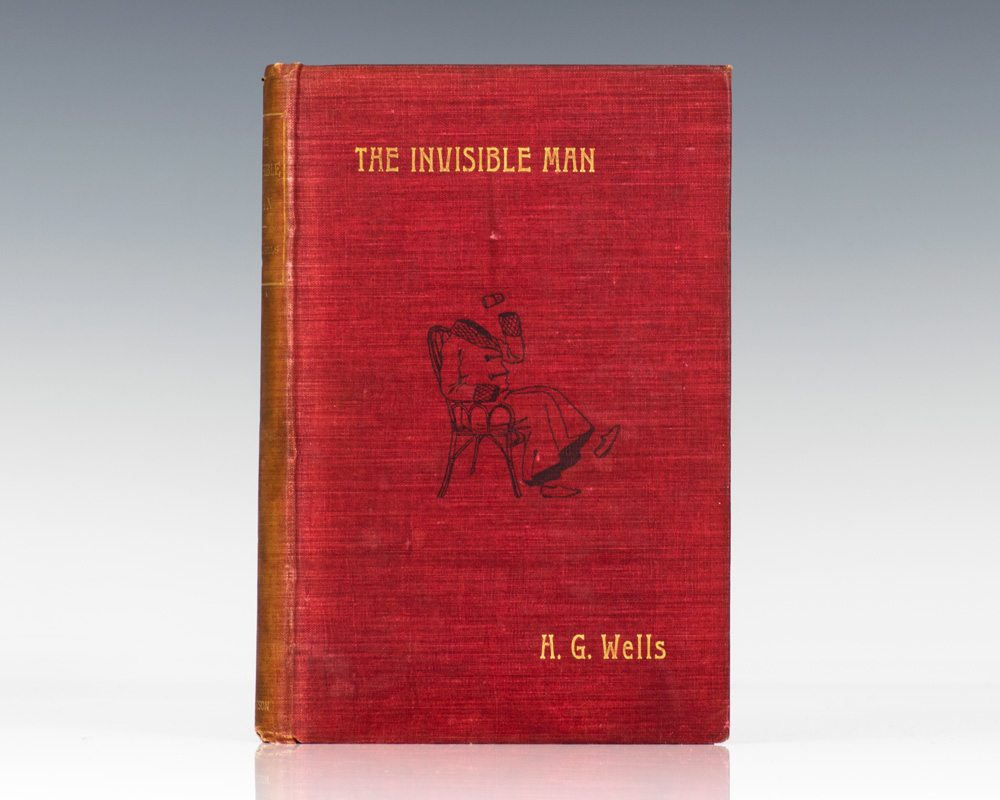

In 1957, the first science fiction book translated from English into Sinhala was published — H. G. Wells’ The Invisible Man was translated by B. Shanthideva Shatweera and is published by M D Gunasena publishers.

Welihinda Munirathna wrote a novel called මාරක ඇටසැකිල්ල (Deadly Skeleton) during this period. It told the story of a man dressed in a black latex suit with a skeleton painted in radium on it. The man would terrify others in the dark, using the glowing radium on his suit to extort money from innocent victims.

Another author, Sirisena Maitipe wrote මා නැති දවස (When I’m Not There) reinterpreting the epic saga of Demon King Ravana and Rama as a nuclear war between the warring factions, also around this time.

The One That Ticked All The Boxes

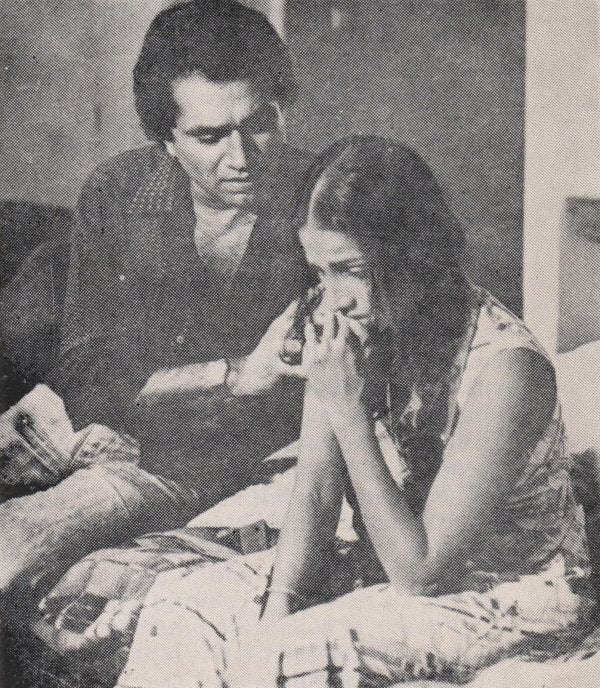

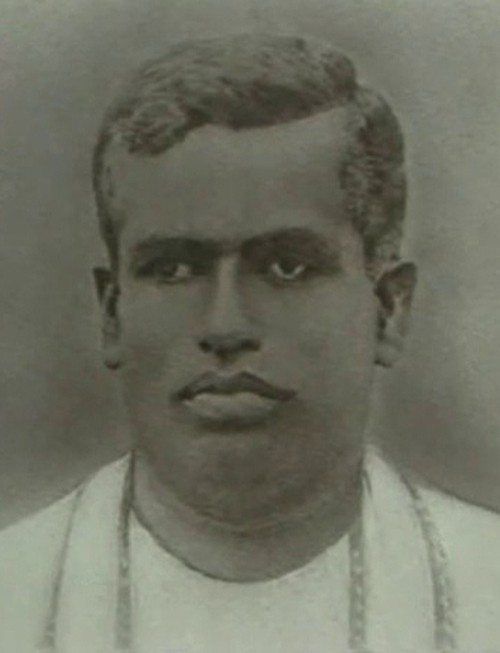

The early sixties also saw the arrival of K. A. Lionel Perera, recognised as the first author to pen the first pure science fiction in the Sinhala language.

A music teacher by profession, Perera wrote and published 1988, a short story about a woman giving birth to a baby, deformed from being exposed to radiated toxic waste from Japan. The baby eventually grows into an adult and transforms into a three-eyed monstrosity with a penchant for violence but an innocent, child-like affection for his mother. This, many agree, is the first piece of Sinhala literature that ticked all the boxes of what constitutes science fiction.

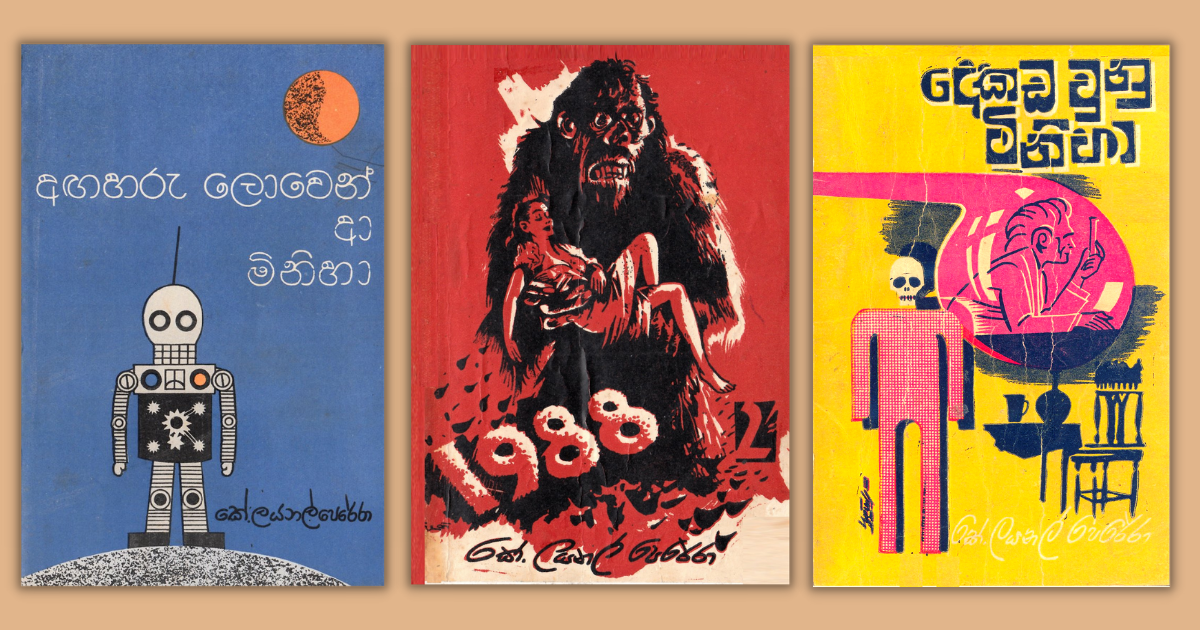

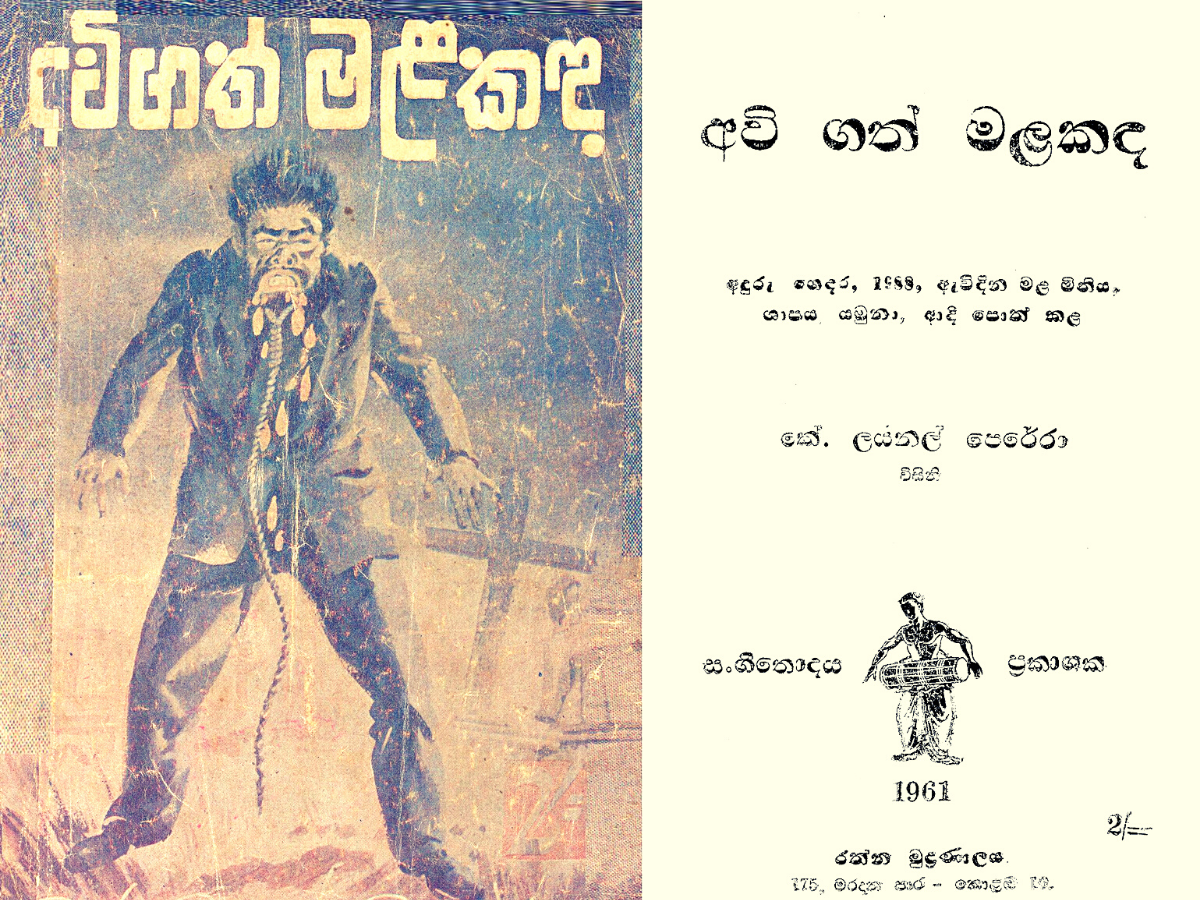

Perera would go on to write several other novels අගහරු ලොවින් ආ මිනිසා (Man From Mars) in 1959, අවිගත් මළකඳ (The Armed Cadaver) in 1961, දෙකඩ වුණු මිනිසා (The Split Man) in 1966 and අඩි දහතුනේ මිනිසා (Thirteen Feet Tall Man) in 1976.

Man From Mars was the story of a Martian warlord who conquered Earth, whose plans were spoiled by a Sri Lankan scientist, the Armed Cadaver, incorporating elements of horror, was a continuation of his first novel, 1988. He also wrote a third sequel to this story — making it a trilogy — the final novel being named 1990.

Many of Perera’s stories were similar to other stories coming out from the other end of the world. Man From Mars has some similarity to Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter of Mars and the Thirteen Foot Tall Man is somewhat similar to the 1958 American movie, Attack of the 50 Foot Woman.

The Translations And The Future

Despite the increased demand for speculative fiction, it is but rarely an avid reader would come across independent Sinhala science fiction. The main reason for this is the much larger demand for translated science fiction — a popularity that began during the 70s.

Even the works of the sci-fi giant the late Sir Arthur C. Clarke, who lived in Sri Lanka, gained popularity — during his lifetime and after his death — due to the translations by S. M. Banduseela.

Banduseela’s first translation came out in 1978, when he published Desmon Morris’ The Naked Ape when he was in his 20s. In his early 60s now, he has translated almost all of Arthur C. Clarke’s work and a dozen other science fiction novels.

A database compiled by Vidusrara — Sri Lanka’s only weekly science magazine — writer Sandun Sameera Siribandu has recorded 300 science fiction books that have been published since 1957 to 2021. Of the 300 entries, only 133 are independent science fiction, the remaining 167 are translations.

But these numbers should not be perceived as disappointing. Science fiction as a genre is still very young, and its potential, limitless. With Sri Lankan authors such as a Yudhanjaya Wijreratne and Naveen Weeratne now making strides in the international science fiction circles, the future of the Sri Lankan science fiction — whatever the language — does not look bleak.