When 45-year-old Chathurya* gave her 13-year-old son a smartphone, she didn’t see any potential drawbacks. “All his friends are hyperconnected, and considering myself a rather progressive mum, I didn’t buy the argument that people were less connected in the ‘real world’ because of friendships pursued online,” she told Roar Media. “Furthermore, given the evidence that the skills acquired during gaming helped develop strategic thinking and motor skills and also knowing the benefits of having knowledge at my fingertips, I thought Mahesh* would benefit from it,” she said.

The last thing Chathurya expected was for Mahesh to become more and more dependent on the palm-sized device. “He was doing well at school and playing sport for his team and I thought he was well-balanced, but the incessant tap-tapping on the phone increased, especially during the holidays when he had ‘nothing else to do,’” she said. “He also became more and more closed-off and uncommunicative, and although we put this down as ‘normal teenage behaviour’, we were worried.” The tipping point came when Chathurya noticed scores of neat horizontal scars across Mahesh’s forearms.

“I was shaking,” Chathurya told us. “I grabbed his arm and demanded to know what had happened.” But the answer was convoluted: “Mahesh said it wasn’t serious, and that other boys in school were doing it too.” Both alarmed and dissatisfied with his answer, Chathurya pressed further, threatening to take the matter to the school principal. Mahesh’s rambling answers were inconclusive and it was difficult for Chathurya to understand why her son was cutting himself – or indeed, why other kids were harming themselves, as Mahesh had reported.

Chathurya decided to take her son to a counsellor, who referred her to Dr. Lalith Mendis, the former Head of Pharmacology at the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Kelaniya. Dr Mendis, who currently functions as the Director of the Empathic Learning Centre in Colombo and as the Founding Director of the Centre for Digital Science, Right Learning, Career and Choices, campaigns tirelessly against digital addiction. He explained clearly the way digital devices affect the brains of children and teenagers, impacting their behaviours.

Brain Activity

“Reducing screen time from a young age is very important,” Dr. Mendis said, explaining that children should be allowed no more than 25 minutes in front of a television, iPad or another screen. “Cartoons with a high pixel per inch (PPI) and rate of pixel change, coupled with the intensity and variability of sound and colours causes ‘pixel-driven neurotoxicity’, a condition that causes attention span deficits, boredom and chronic fatigue from dopamine depletion due to digital overuse. Learning becomes uninteresting, the regular becomes boring and the fantastic becomes the craving,” he said.

For children younger than two-and-a-half, digital overuse is believed to contribute to delays in speech development. “Parents come to me and say, ‘My son (or my daughter) is so smart, he knows this and that, and they attribute this knowledge to the digital device(s) the child is using. But later they come to me in tears—their child is finding it difficult to adapt to a new language in school, he is unable to cope—and why? This the reason why,” said Dr Mendis.

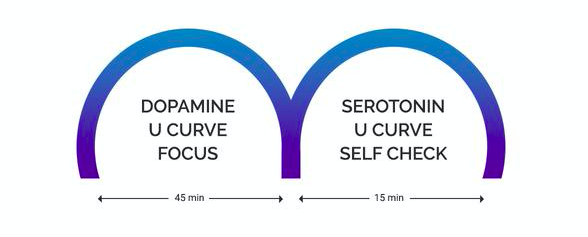

The more the digital stimulation, the more dopamine is secreted to the brain. Although dopamine is commonly known as the ‘happy chemical’, what it does is to signal the value of a reward to the brain, which in turn provides motivation. Dopamine does this through what is known as a ‘Dopamine U-Curve’, which refers to when dopamine regulates itself by taking a U-turn, making way for another brain chemical: serotonin. Serotonin conducts a ‘self-check’, evaluating satiety and satisfaction, before taking a U-turn itself, making way once more for dopamine.

Dopamine is usually active in the brain for no more than 45 minutes, before the naturally-occurring U-turn takes place, giving way to serotonin, which is active for about 15 minutes. This is why Dr. Mendis advises that no brain activity is conducted for more than 45 mins without a short break. When children—or adults—spend long hours on a digital device, the brain has no time to evaluate or reflect on the work it has just done to ask the important questions: Have I understood this correctly? Was this done right? What more can be done to make this better?

Digital Addiction

Once a child, or teenager, becomes accustomed to the ‘high’ derived from the excessive dopamine produced in the brain, she begins to want to replace the high when she becomes dopamine-depleted, which can lead to addiction. As Jomo Uduman, Honorary Director of Mel Medura, an organisation affiliated to Sumithrayo that helps people struggling with behavioural addictions, explained: “The failure to resist an impulse, drive, or temptation to engage in a behaviour that is harmful to the person or to others is the essential feature of an addiction. Digital addiction falls into the category of ‘behavioural addictions’ like pornography, computer gaming and gambling.

“When a person is ‘digitally addicted’, there is an increase in tension, restlessness or irritability that becomes apparent when it is impossible to use the device, and increasing amounts of the activity is needed to reach satisfaction. More alarmingly, social, occupational, academic or recreational activities are often given up or reduced to make room for the behaviour: Digital addiction becomes the most important or central activity, dominating thoughts, feelings and behaviour. In this way, behavioural addicts, such as those digitally addicted, are no different to those who abuse and misuse harmful substances like alcohol and other drugs,” he said.

It isn’t that only young people are susceptible to digital addiction. Jomo explained that the risk of addiction to devices is high for all users. “When excessive time is spent on digital devices, it takes you away from connecting with the real world and importantly, from acquiring life skills that will help you cope with real life situations and the challenges and crises in your life,” he said. “It reduces the opportunity to develop and practice ‘emotional intelligence’—the key elements of which are self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy and social skills—and social scientists have already indicated the importance of emotional intelligence (EQ) over IQ.”

This became apparent to Chathurya, who through counselling and support, discovered that Mahesh was cutting himself in frustration at his inability to deal with the pressures of school and his peers. While at first she couldn’t comprehend why he would choose to hurt himself, Dr. Mendis explained that the behaviour could have physiological reasons. “Although children themselves may not know the psychology behind their actions, references to violence and pain online prompts them to experiment and thereby experience the ‘sweet release’ that occurs when endorphins, a naturally produced morphine, is released in the body,” he said.

Taking Control

Dr. Mendis warned that digital addiction could also affect sleep and eating patterns. “Digital overuse suppresses the secretion of melatonin, the hormone that regulates sleep and wakefulness,” he said, adding that the effect was worse when children use devices after 6 pm, when the brain begins to prepare for sleep. This became evident to Nilu*, whose 17-year-old son, Thilina*, began to stay up all night gaming with friends from across the world. “He would still wake up and go to school on time,” she told Roar Media, “and his grades were fine, so I didn’t know if I should make a fuss.”

But a few months on, Thilina’s grades dropped and he found himself floundering, unable to manage his life. It took several months to get him back on track. Nilu wishes parents had more guidance in this area. “ We didn’t know what he was doing was unhealthy, so we didn’t actually prevent him at the beginning,” she said. This is one of the reasons why Dr. Mendis is so committed to educating schools, parents and religious organisations on how important it is to guard children and adolescents against digital addiction. “ It’s best to delay giving a child or teenager a phone until after his Advanced Levels; if possible, even later,” he said.

Jomo also pointed out the responsibility lies with parents to influence the behaviour of children. “Adults must be conscious of their own habits, if they want to moderate their children engaging with technology and media,” he said. “When a child observes a parent frequently distracted by his phone, she may wish to imitate that behaviour. We need to set boundaries for work-time, social networking and family time.” And even while Jomo agreed that less time on social media may be the best solution, “learning how to use social media in a way that will boost well-being rather than hinder it will also play an important part,” he concluded.

[Cover: Director of the Empathic Learning Centre, Dr. Lalith Mendis, who has campaigned tirelessly against digital addiction, sees increased dependency on digital devices as retrogressive rather than progressive. Image courtesy: ft.com]