The unexpected question caught Samadhi* (22) off guard, and she paused a moment before answering. The composure she had displayed thus far cracked, and her eyes welled up.

“People make mistakes,” she answered finally. “[But] that doesn’t mean they have to be murdered.”

Samadhi’s mother, Kumudini* (42), was arrested in 1999 for possessing 150 mg of heroin. Samadhi doesn’t believe her mother ever did drugs. She told Roar Media the contraband belonged to her father, who had refused to take responsibility.

Kumudini was sentenced to death in 2011. “She was pregnant at the time, so the order was reduced to two life sentences. I couldn’t bear it. I collapsed when I heard the news,” Samadhi recalled.

Kumudini’s younger brother was born in prison, and is now seven years old. It’s Samadhi, who, together with the help of relatives, takes care of her younger siblings. Their father absolved himself of all responsibility and kicked the children out in May last year.

But even as Samadhi and her younger sister and brother struggle to come to terms with the loss of their mother and the abandonment by their father, a new fear grips their hearts. With President Maithripala Sirisena announcing his intention to enforce the death penalty, they may lose Kumudini forever.

Photo credits: Nirasha Piyawadani/ GPJ Sri Lanka

The Death Penalty

The last time the death penalty was imposed in Sri Lanka was in 1976. The sentence has since been automatically commuted to life behind bars. But President Sirisena interest in imposing capital punishment has brought up a gamut of issues, not least the question of if it is morally justified.

This is not the first time President Sirisea has wanted the death penalty imposed. He brought the matter up in 2015, to deter rising crime, particularly the rape and murder of four-year-old Seya Sandewmi. But nothing came of that announcement.

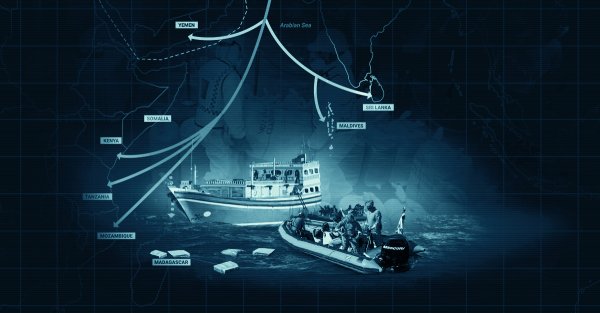

Now, despite criticism and a heavy backlash, he seems intent to revive capital punishment, this time, in a bid to crackdown on drug smuggling. A private member motion to declare the death penalty illegal has also been dismissed as illegal.

The Ministry of Justice, the trial judges and the Attorney General’s Department have identified over 450 death row inmates, 30 of whom are convicted on drug-related charges, and the President has greenlighted death to be imposed on three selected men and a woman.

For Samadhi, this is chilling news: because the President has held back from revealing who the selected criminals are, there is no guarantee her mother will not be one of the four on whom the death penalty will be imposed.

What About Us?

Samadhi is not the only one unhappy about the coming course of action. The family of four-year-old Seya Sandewmi is enraged with the President’s seeming duplicity, arguing that capital punishment should be imposed on criminals convicted of rape and murder first.

“If it is being implemented on them [drug smugglers], why not [on] these child molesters and murderers?” Seya’s 40-year-old father asked Roar Media. “Especially when it has been proved with DNA.”

Although Seya’s murderer was sentenced to death in 2016, his sentence was commuted to life behind bars, which is the norm.

“Just because he is in prison doesn’t mean there is any difference,” Seya’s father said bitterly. “When he was out of prison also, it wasn’t like he lived decently. But at least he had to work for his money. Now he is in prison and eating and drinking on our money.”

Photo credit: Ceylon Today / Tharaka Basnayaka

Death As A Deterrent

Further compounding issues is the fact that death has not proved an effective deterrent to crime.

Writing to the Sunday Times, Forensic Specialist Professor Ravindra Fernando reiterated the widely accepted argument— ‘there is no evidence that the death penalty is any more effective in reducing crime than life imprisonment.”

So widely accepted is this, that only 53 of the 193 countries of the world currently still impose capital punishment—Madagascar (2015), Benin (2016), Guinea (2017) and Burkina Faso (2018) being the most recent to abolish the death penalty.

The irreversibility of the death penalty and the high possibility for wrongful imprisonment— as suspected in the case of Kumudini—especially in countries with less-than-robust judicial systems and processes like ours, has also been flagged as a significant point of concern.

Sri Lanka’s justice system is riddled with long delays and systemic failures. As of 2018, 3, 486 cases were pending in the Supreme Court, 4, 817 in the Court of Appeal, 5, 890 in Civil Appellate High Courts and 16, 811 in High Courts.

Further to this, a whopping 167,945 and 535, 644 cases were pending in the District and Magistrates’ Courts respectively, and a further 5,048 in Labour Tribunals.

Just this year, in a study of seven emblematic cases in Sri Lanka, the Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA) noted large time lags, of over 10 years, in some cases, and called for better accountability in the country’s justice system.

Social Security

There is also the matter generally unconsidered: for instance, what happens to the families of those on whom the death penalty is imposed? Chairperson of the Committee for Protecting the Rights of Prisoners (CPRP), Attorney-at-law Senaka Perera said the state does not currently have a welfare programme for the benefit of families.

This means the families and any dependent of the incarcerated convict and the convict on whom the death penalty is imposed will continue to have to bear the economic burden and social marginalisation of the loss of a family member.

In the case of Samadhi, who already bears the economic burden of her family, social marginalisation has materialised well into her young life.

“When I was studying for my Advanced Level exam, a teacher in my school learned that my mother was on death row,” Samadhi told Roar Media. “She spread the information to the entire school. She told my friends to stop associating with me. My best friend was asked to stop being my friend. I couldn’t handle it. With six months left for the exam, I dropped out,” she said.

Samadhi’s and Seya’s stories are but a fraction of the larger picture. The fact is that the debate about capital punishment is far from being answered. And in an election year, there is a palpable risk of it becoming reduced to an electoral gambit.