For the last two months, Tharusha’s* (13) daily routine has been the same; wake up, watch TV, play outside, read a book, go to sleep. But Tharusha is the only one from his class doing that. For in the last two months, his friends have hit their books again. Their teachers send them lessons through WhatsApp, and the students follow instructions at home.

But Tharusha’s family does not own a smartphone.

Living in a small house close to Marine Drive, Dehiwela, Tharusha’s father is a small-scale vegetable vendor while his mother is employed at a janitorial service. While both parents are away at work, Tharusha is taken care of by his grandmother, who lives with them.

The Unlikely Rise Of WhatsApp As A Learning Platform

“His teacher called and asked us whether we have access to WhatsApp. But I told them that we only have a small phone [feature phone],” Rosalin Nona* (62), Tharusha’s grandmother told Roar Media.

Schools were closed on March 12 as a preemptive measure against the spread of COVID-19. With no reopening date in sight, administrative authorities and teachers have mobilised to try and conduct academic activities through digital means. And due to its ease of use and popularity amongst smartphone users, WhatsApp has emerged as the platform of choice for teachers.

“Soon after the Avurudu holidays, our principal told us that he had received instructions from the Zonal Education Office to disseminate lessons through WhatsApp,” Hema Punchinilame* (53), Tharusha’s class teacher told Roar Media.

For Punchinilame, who has been teaching for more than 20 years, delivering lessons through WhatsApp is a novel experience. “This is the first time I am doing something like this. We created WhatsApp groups for each class, and added all the relevant teachers to each group along with the students. Every teacher posts lessons and instructions on the group. The students seem to be following our instructions, but we can only see the results of this experiment once school reopens,” she said.

But what happens to students like Tharusha, who have no access to smartphones?

“Paw, e lamai” [poor children], Punchinilame said. “They have no way of following these lessons, and for no fault of theirs. I personally try to only give students exercises which are easy to grasp, so that I can explain the harder lessons in detail to all the students once school reopens. That way, at least the students who have no access to smartphones won’t fall behind by much,” she said.

Error 404: Device Not Found

Sri Lanka was one of the first countries in the world to embrace the concept of distance learning, when it established the Open University of Sri Lanka in 1978, a mere nine years after the United Kingdom. Since then, however, the growth of e-learning has been hampered due to various issues, especially at the primary and secondary education levels. Chief amongst them is access to internet-connected devices.

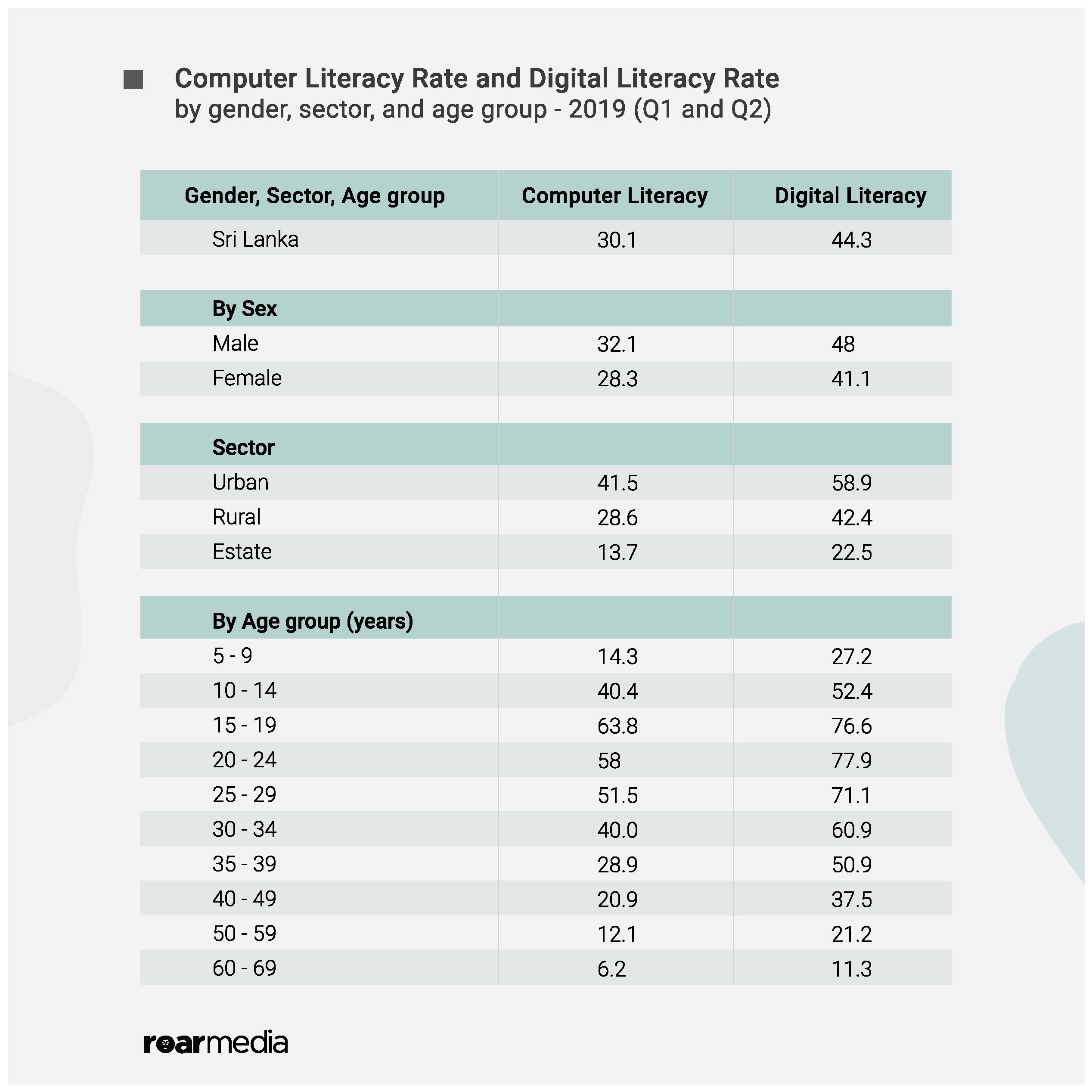

According to the latest available data from the Department of Census and Statistics, Sri Lanka’s computer literacy rate (as defined by whether a person can use a computer on their own) stands at 30.1 percent. However, the digital literacy rate (as defined by whether a person can use a computer, laptop, tablet, or smartphone on their own) is significantly higher at 44.3 percent.

This development, while encouraging, also means that the vast majority of Sri Lankans still do not have access to the internet. A previous government raised a proposal to distribute free tablet computers to students, which technically could have increased device accessibility, but never came to fruition.

The Content And Data Question

“I use Ammi’s phone to keep up with the lessons on WhatsApp. But I wish there was a better, more interactive way to learn. This is very boring,” Dilmi* (16) a student at a girls’ school in Kandy told Roar Media. Currently preparing for her G.C.E. Ordinary Level exams, she said: “For students like me who are getting ready to face an important exam, it is important to have an easy way to obtain feedback from teachers. Having some videos and explanations will also be nice. But then, you have to think about the data charges.”

For e-learning to work, access to devices and the internet needs to be complemented with a rich ecosystem of content that is both interactive and easy to consume. To its credit, Sri Lanka does have its own national e-learning platform—e-Thaksalawa, which is powered by Moodle. Moodle is an open-source Learning Management System (LMS) popular with universities and schools around the world. The site is free to use and users will not incur data charges as per the directive of Sri Lanka’s Telecommunications Regulatory Commission.

Although e-Thaksalawa has a vast volume of learning material for every subject from Grade 1 to 13 in all three languages, its poor usability and lack of smartphone responsiveness is its Achilles heel. In a country where almost 71 percent of households go online through their smartphones, the absence of such features means fewer students are inclined to use these platforms.

“Maybe they can include things like games and quizzes. Then it will be fun for us as well,” Dilmi contemplated aloud.

And she is right. Perhaps it is time to reimagine e-learning in Sri Lanka to suit the smartphone age.