A phone rings.

“Is this a good time?”

“You have all the time you need. We are walking, as you know, on a very delicate area…it is very important that this conversation is held in as responsible a way as possible.”

Thus begins a conversation between Sam Harris, American neuroscientist and author, and Maajid Nawaz, once a radical British-Pakistani Muslim. The latter was arrested in Egypt for his work with Hizb ut-Tahrir, a political Islamic movement seeking to establish a global Islamic state.

Harris and Nawaz first met in New York in 2010. Harris was in the audience watching a debate centered around the topic Is Islam a Religion of Peace?, which Nawaz defended. Their initial meeting was at a closed-door dinner party after the debate, where Nawaz took offence at a question Harris asked him — whether Nawaz truly believed that it was a religion of peace, or if he was pretending, hoping it would eventually turn true one day. The situation was so tense that attendees at the dinner half expected a fist-fight to break out, before intervening and changing the conversation.

No one expected Harris and Nawaz to be on speaking terms after, but four years later, in 2014, Harris reached out to Nawaz asking if they could continue their conversation. What ensued was a long phone conversation discussing radicalisation, interpretations of the Quran, differences between Islamists, jihadists, and reformist Muslims, and global extremism.

For Nawaz, Islamism was a purely political ideology.

“When I say Islamist, I mean the desire to impose any given interpretation of Islam over society. Jihadism is the use of force to spread Islamism…” he elaborated, clarifying that groups like ISIS and Al-Qaeda were jihadists, whereas Hizb ut-Tahrir was Islamist.

The reformist Muslims, he says, are the ‘smallest minority’. They are “those who recognise the problem, recognise openly that there are troubling passages in scripture that require re-interpretation, and recognise that there are people within the Muslim community who are theocrats and need to be challenged.”

The outcome of this conversation was a book co-authored by Harris and Nawaz, titled Islam and the Future of Tolerance: A Dialogue. This was published in 2015.

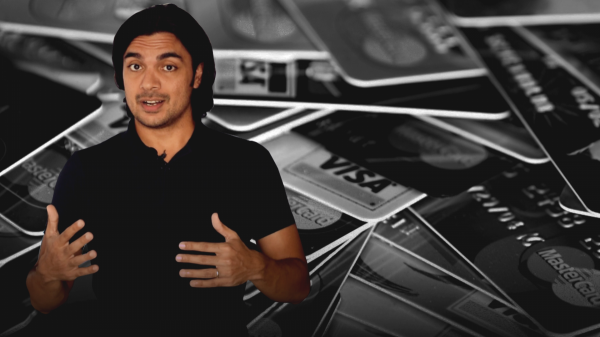

By December 2018, an eponymous documentary—co-directed by Desh Amila, a Sri Lankan living in Australia—was released.

From A Phone Call, To A Documentary Film

“I didn’t get into filmmaking until two years ago,” Amila tells us over a Skype conversation from Australia. “There’s no clear way about how you can get in to film, like IT, or investment banking. So I got into radio, and eventually did my own radio show.”

His shows were a resounding success, and opened avenues into the event sector. One thing led to another, and soon, Amila was working with Think Inc., a collective which organised events and discussions around challenging topics. In 2015, he pulled together an event featuring both Harris and Nawaz, and filmed it, intending to upload the clips on to YouTube much later. Going through them, Amila realised he had an “extraordinary story”. Things began to fall into place from thereon. Jay Shapiro, a documentary filmmaker based in New York, had been following Think Inc. on social media. After watching the event, he messaged the organisation hoping that the interaction was being recorded. Thereafter, he and Amila partnered up to produce the documentary.

Harris’ recording of the conversation between himself and Nawaz is used as a conduit throughout the story, along with other footage and clips of cataclysmic events such as 9/11; the rise of Combat 18, a neo-Nazi organisation in the United Kingdom which attacked people of colour and Muslims, partly contributing to Nawaz’s turn towards radicalisation; other incidents of similar violence, and Hizb ut-Tahrir’s recruitment video.

The documentary opens with the conversation between Harris and Majid, and then follows both of them through their experiences, perceptions, and the reasons for their beliefs. It juxtaposes Harris’ view of Islam after the September 11 attacks, and how he wrote his best-selling novel The End of Faith a mere few days after it, with Nawaz’s experience of anti-Islamic and anti-Pakistani sentiments halfway across the world, which pushed him towards radicalisation.

In the film, Nawaz makes a distinction between the political and religious reasons for joining Hizb ut-Tahrir: “…that’s crucial to understanding what Islamism is all about: it isn’t a religious movement with political consequences, it is a political movement with religious consequences.” It then goes on to explore, respectfully, Harris’ queries — such as the reasons why Islamic radicalisation is a global issue, and why it is undiscussed within mainstream Muslim communities.

Addressing “The Muslim Question”

For Amila, the primary aim of the movie is about conversation, and how to have one without losing one’s humanity.

“When we talk about Islam, and when you go online, it is denigrating a group of people. The far right wants to pin the entire world’s problems on Muslim people. Then you have the left not wanting to talk about this subject matter, because they’re worried about marginalising a group. So they choose to not talk about it at all, and prevent conversations from happening. The left is very sympathetic towards minority rights but unintentionally, they’re hurting the group of people they want to help by not having this conversation,” he elaborated.

Breaking Into The Industry

One of the biggest challenges Amila and Shapiro faced was for the documentary to be taken seriously by established film bodies, distributors, and organisations.

“I’m a first-time filmmaker, and we didn’t go through traditional routes of making the movie,” Amila recalls. “We were treated as outsiders, the subject matter was controversial…and so on. I think one part was perceived lack of experience, and the other part was subject matter.” People were hesitant to publicise or support it because it touched upon Islam.

In addition to that, theatrical releases have been hard. The movie premiered in Los Angeles, and there was a screening in New York, but the primary avenues to access it are digital platforms like Vimeo and Amazon Prime. Currently though, the team is working with a subsidiary of Sony acting as their distributor, and has an arrangement with FanForce, a user-driven screening platform.

On the plus side, however, funding was never an issue. Amila’s business was profitable, and initial funding came from that. Thereafter, they launched a kickstarter campaign and raised a “reasonable amount of capital,” according to him.

“I believe we’re the third-highest fund-raised Australian documentary,” he said, adding that the film also got philanthropic donations from independent donors.

Besides, the documentary has been received with critical acclaim: it is rated 5/5 on Amazon Prime, and 9/10 on IMDb.

Dialogue And More

Muslims are often perceived as a homogenous community. Internationally, there is little awareness about the diversity within the community. The documentary addresses this, in addition to the difference between ideology and religion.

Other than the obvious reason for making it—which was to make the most of the opportunity and content he had from the event featuring Harris and Nawaz—Amila also wanted to spark a conversation.

Among other things, his experience as an immigrant filmmaker has itself been interesting for Amila.

“I haven’t been able to get a single journalist [in Australia] to speak to me,” he said. “In America, it was very interesting. A lot of people assumed I was Muslim because I was brown.”

This disconnect—and misunderstanding—that exists about who is Muslim, is one of the reasons that Amila decided to make the film.

“There’s a lack of understanding of who is a Muslim — people don’t understand the difference between the people and the ideology; between who is a Muslim and what is Islam.”

What the documentary does, he said, is to help people talk and learn from each other.

“Some people think there’s going to be answers…but the movie doesn’t have any. It only gives you the tools on how to have a conversation.”