It is often the case that when a nation is blindsided by tragedy, its people will translate their grief into fear and anger. This is what graphic designer and illustrator, Tahira Rifath, found to be the case when a series of coordinated explosions hit Sri Lanka on Easter Sunday, killing 258 people and injuring scores more.

In the aftermath of the attacks, Rifath felt immense grief over what had happened, and yet, when she went on to social media or turned on the news, she didn’t find this feeling reflected back at her.

“When I opened Twitter, all I could see were people fighting, and accusing each other of various things,” she said. “I was up till 7 AM, not sleeping, just wondering about the people who went through this; what kind of trauma they must be feeling. I’m sure others felt this way, but that isn’t how people seemed to be communicating.”

The attacks have prompted furious online debates about the failures to national security, the spectre of global terrorism and a growing distrust amongst communities. These narratives dominated Rifath’s newsfeed, and she felt the victims had been buried once again beneath all the noise.

This is when she decided to pay tribute to them herself, by embarking on the arduous task of drawing a portrait of each person who died as a result of the attacks.

“I felt the need to centre [on] them in some way,” she said. “When the New Zealand attacks happened, their Prime Minister refused to give the perpetrators the spotlight. But when the attacks happened in Sri Lanka, that is exactly what we did. I saw all these articles being shared about who the bombers were, but I barely found the articles about the victims being shared. They just became reduced to a number.”

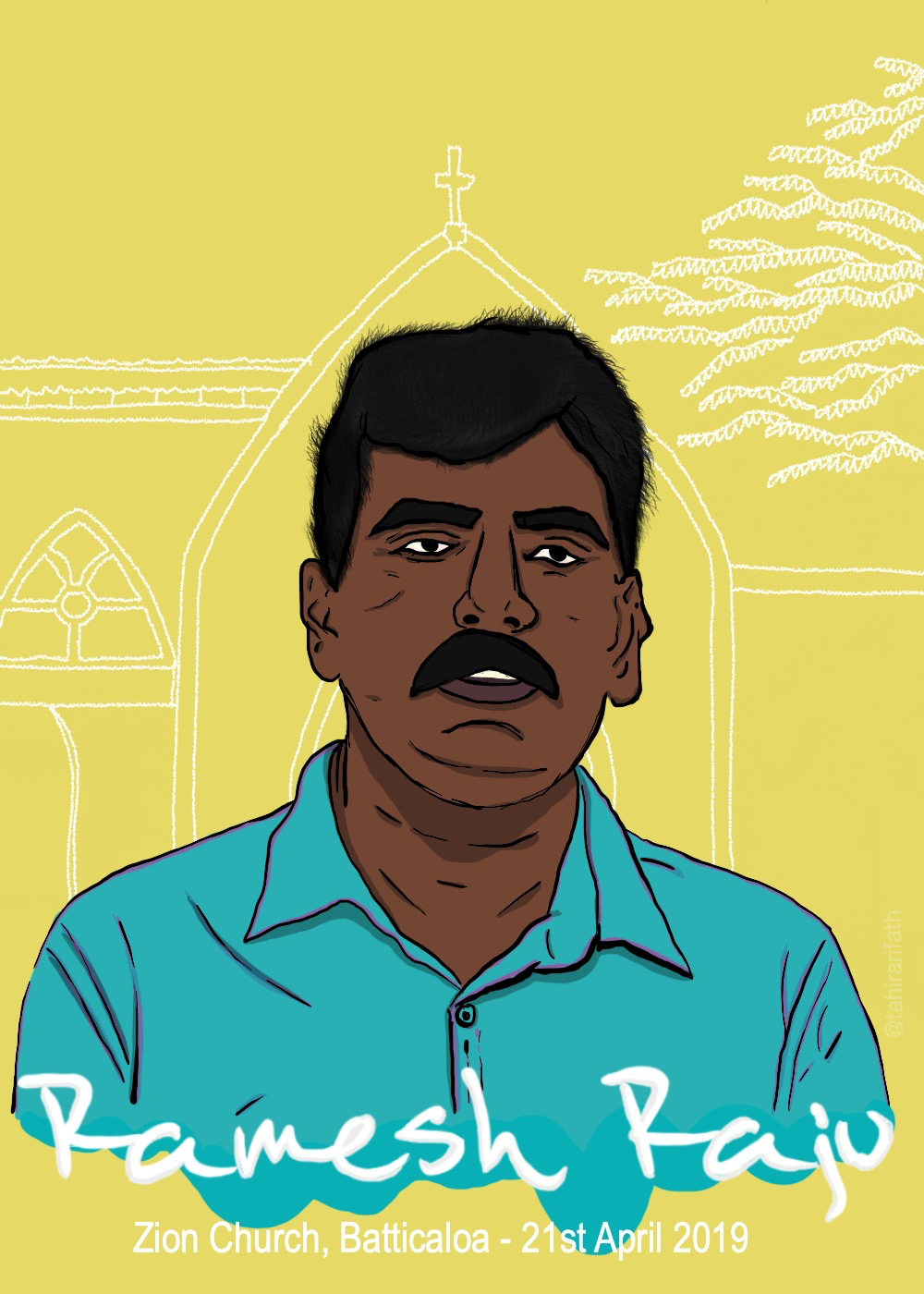

So she began her first portrait — of 40-year-old Ramesh Raju. Raju was a building contractor and a father of two. He lost his life attempting to prevent the bomber at the Zion Church in Batticaloa from entering the church, saving the lives of many attending the service, including his family. Had it not been for Raju, there would have been many more casualties.

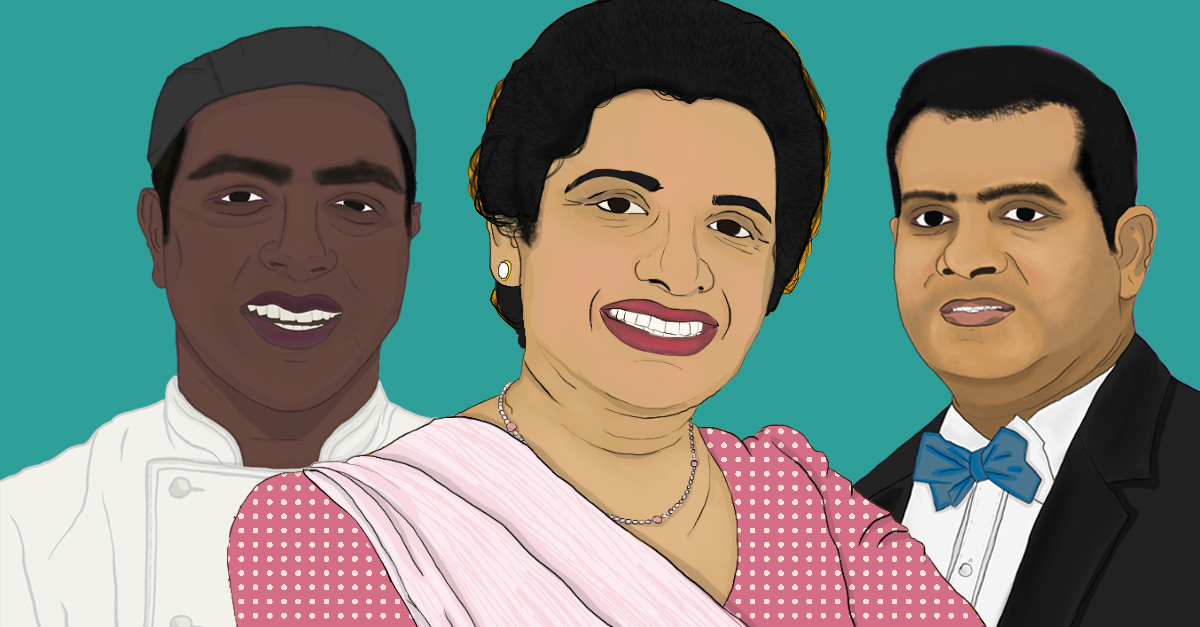

“I started with Ramesh Raju because I came across an article written about him, and there was enough information on him already out there,” she said. “Once I posted his drawing, more people came forward. For example, [the] management at Cinnamon Grand gave me information on their staff members that were killed. I drew them next.”

Rifath’s process begins on Facebook, where she tries to find photographs and information on the victims from their profiles. When she is able to, she locates family members and friends of the victims who are willing to speak on their character.

This is a time-consuming task, but thankfully, she does not have to do it all herself and has a few friends helping her with gathering and cross-checking information. When this is done and she has a reference photograph ready, she goes straight to her Mac, and begins drawing.

Although Rifath accompanies her drawings with descriptions, she tries hard to incorporate a sense of who the person was through the image. By paying attention to clothing details, and sometimes including illustrated backgrounds, the personalities behind the images begin to take shape. They become recognisable human beings — and their loss, tangible to the viewer.

“I feel like I get to know the people I draw,” she said. “When I began my first drawing, halfway through, it just hit me that this person isn’t there anymore, and the weight of that sunk in. I think that weight is what drives me to see this project all the way through. I don’t want the last image that their loved ones see to be the image of them in a casket.”

Of the 258 drawings she aims to complete, Rifath has completed eight. If anyone has any information on the remaining victims of the Easter Sunday attacks that they would like to share with Rifath, contact her at: rifathtahira@gmail.com.

.jpg?w=600)