Years, as they go, are tumultuous, but Sri Lanka wound her way magnificently through the last one. Braving incidents as horrific as the Meethotamulla tragedy, the protracted drought that engulfed a swathe of the nation, and cyclone Ochki that raged through parts of the island, Sri Lanka, nevertheless, made meticulous progress on several fronts. Here are a few things that Sri Lanka did right in 2017.

Implementing the Right to Information Act

When the Yahapalanaya government took over reins in 2015, it made a number of pledges spanning 100 days. Among these was the promise to enact the Right to Information Act within three weeks of February 20, 2015. Despite these ambitions, Cabinet approval for the draft Bill was only granted on December 2, 2015, after which it was sent to the provinces for discussion.

While the Western, North Western, Central, Southern, Eastern, and Uva Provinces agreed with the contents of the draft Bill, the Sabaragamuwa, North Central, and Northern Province wanted amendments made to it. The draft Bill was finally presented to Parliament for first reading by Parliamentary Reforms and Mass Media Minister Gayantha Karunathilaka on March 24, 2016.

After several rounds of discussion, the draft Bill was passed with amendments on June 24, 2016, receiving the support of all 225 members of Parliament. Under the Act, citizens are ensured the right to request for information in the possession of any public authority. The Act, however, only came into effect on Independence Day—February 4, 2017, two years after the current government took over.

Local university students and members of the Government Medical Officers’ Association protest against SAITM. Image courtesy nation.lk

Resolving the issues relating to SAITM

The issues surrounding the medical faculty attached to the South Asian Institute of Technology and Medicine (SAITM) had reached a fever-pitch before the government intervened to finally abolish SAITM on October 29, 2017.

It had previously offered to take over the Neville Fernando Teaching Hospital and a host of other compromises in a bid seek ‘middle ground’, but the offers were rejected by the Government Medical Officers’ Association (GMOA) and the protesting local university students.

The GMOA and the local university students had launched an indefatigable attack on the government in the form of strikes and protest that affected the public. University students also stormed the Health Ministry, resulting in over 80 students being injured in the ensuing clash with law enforcement officers.

The protests severely crippled medical services as people were left stranded in government hospitals, and inconvenienced the general public who had to bear the brunt of the street protests. While the move by the government resolves the SAITM issue, the conflict between state and private education still persists.

Regaining GSP+ trade concessions

Sri Lanka lost access to the lucrative European Union Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP) Plus trade concession on February 15, 2010, for “significant shortcomings” in the implementation of “three UN human rights conventions relevant for benefits under the scheme”.

This was largely due to the previous government’s disregard for human rights and its dismal track record with the international community. The new government, however, that was formed in 2015, made regaining GSP+ trade concessions a priority.

Accordingly, an application seeking to regain access to the GSP+ trade concessions was made on June 28, 2016. In October 2016, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe travelled to Brussels, Belgium to recommence talks with the EU.

After a protracted period during which the EU reviewed Sri Lanka’s application concurrent to her human rights record, Sri Lanka was once more granted access to the GSP+ trade preference on May 16, 2017. Under the scheme, Sri Lanka will benefit from GSP+ until 2021, when it becomes a middle income country.

The GSP+ trade preference grants a full removal of tariffs under the standard scheme. This allows Sri Lanka to export upto 60,000 products to European Union countries duty-free, boosting the country’s export sector.

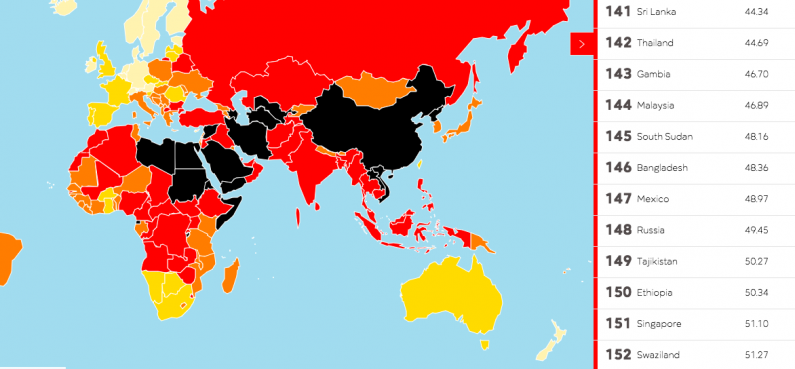

A better ranking on the World Press Freedom Index

Climbing to 141 place in the World Press Freedom Index. Image courtesy rsf.org

The year 2017 marked continued success for Sri Lanka when, after plummeting to as low as 165 from 180 countries on the World Press Freedom Index in 2014 and 2015, she maintained the position of 141 gained in 2016 for a second year running.

The World Press Freedom Index, compiled by Reporters Without Borders, is an annual ranking of countries to assess the freedom given to journalists, news organisations, and netizens, and the efforts made by authorities to respect this freedom.

Ranking 141 for a second year is an indication that improved relations between the fourth estate and the incumbent government are stabilising, and the culture of impunity propagated by the previous government is truly a thing of the past.

Intimidation and attacks against journalists, the murder of Sunday Leader Editor Lasantha Wickrematunge and the disappearance of cartoonist Prageeth Eknaligoda, number among the incidents that caused Sri Lanka to slip down the ranking in the previous years.

The national unity government that was formed in 2015 promised to reverse the damage caused to Sri Lanka in the eyes of the world and opened investigations into a number of attacks against the media and journalists that had seen no progress for years. Investigations into these high profile murders and disappearances are ongoing.

Signing into law the Office on Missing Persons Act

Sri Lanka agreed, by consensus resolution at the United Nations Human Rights Council in 2015, to work towards promoting reconciliation, accountability and human rights in Sri Lanka. To this end, the government pledged to establish 1) an Office on Missing Persons, 2) an Office for Reparations, 3) a Judicial Mechanism with a Special Counsel, and 4) a Truth, Justice, Reconciliation and Non-Recurrence Commission.

The first of these, an Office on Missing Persons Act, was signed into law by President Maithripala Sirisena on June 20, 2017. The Act seeks to “ensure necessary measures to provide appropriate mechanisms to search and trace missing persons, as well as to clarify the circumstances in which such persons went missing, and their fate,” and is not restricted to those affected by the civil war with the LTTE but also those missing during the JVP insurrections.

Becoming Signatory to the Ottawa Treaty

Sri Lanka Permanent Representative to the UN Dr. Rohan Perera deposited the Instrument of Accession to the Ottawa Treaty on December 13, 2017. Image courtesy ft.lk

On December 13, 2017 Sri Lanka became signatory to the ‘Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction’, also known as the Ottawa Treaty.

Sri Lanka became the 163rd country to sign the Treaty, following in the footsteps of countries like Canada, Ireland, and Mauritius—which were the first to get on board in 1997. Thirty-three countries, including the United States, China, India, Pakistan and Russia, are non-signatories to the Treaty.

The move by Sri Lanka comes on the heels of intense post-war recovery, which included demining efforts in the areas of the North and the East. It was estimated that there were over half a million mines hidden in Sri Lanka.

Under the terms of the Ottawa Treaty, a state must destroy all anti-personnel mines under its jurisdiction or control within four years of the Treaty, while ensuring the anti-personnel mines do not pose a threat to civilian populations.

Cover: President Maithripala Sirisena is greeted by SAITM founder Dr. Neville Fernando when he arrived to sign the agreement transferring ownership of the Neville Fernando Teaching Hospital to the government. Image courtesy dailynews.lk