Last March, Sri Lanka was in a state of emergency. Racial tensions which had long been brewing online lead to rioting mobs, who subsequently damaged nearly 500 buildings: including homes, mosques, and businesses.

Businesses across Akurana, Digana, and Katugastota were irreparably damaged, leaving behind buildings which were later condemned. The petrol bombs hurled into these structures shattered more than what they were aimed at: social structures were torn apart.

Three months down the line, victims of the attack are working hard to move forward: with minimal support from the state. People we spoke to across affected areas in the Kandy district stated that other than the initial compensation (of Rs. 50,000 for damaged homes and Rs. 100,000 for damaged businesses), and other than the Attorney-General Department officials valuing the damage, nothing has been done to date.

Despite this, they are committed towards rebuilding their lives and reinforcing values of respect and tolerance within the community. Here are a few of their stories.

A Hundred Thousand For A Life

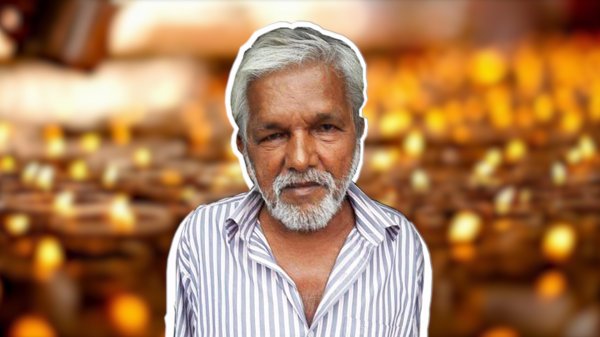

M. Samsudeen was the father of three boys. He lost his youngest, Abdul Basith when the mobs attacked. His eldest son Fazal had married and moved out, but his second and third children were victims of the riots.

I am a pavement-seller. That’s how I did business and took care of my family. We were never rich or well-off, but we never took anything on credit or even a rupee as a loan. I taught my boys to be happy with what they have, to work hard, and study hard. My oldest studied to be a moulavi for over 21 years, and he is one now. My youngest was in the university…he also worked at the phone shop close by. They were all brought up with strong values—and whenever I think of my youngest now, my heart clenches. The pain is indescribable.”

Two doors away from the ruined Masjidul Lafir is an empty space. There are workmen digging along—you can see that it used to be something before.

It used to be the Samsudeens’ home, before it was torched by mobs.

Recounting the panic faced by the family, Samsudeen tells us how he and his wife, both well over 60, managed to get out of the house. Their youngest son (Abdul Basith) was still inside, and their second, Fayaz, was on the roof trying to douse the fire—but in the panic and confusion, they were both unaware of this. Having escaped, the couple ran to the cemetery behind the mosque and hid there with a few other people until the mob passed. When they made their way back down, they were told that the boys were taken to the hospital.

“This was a relief. I was finally able to breathe thinking that my sons were safe. My wife and I were so worried waiting up there on our own, but couldn’t do anything. We heard people say they were taken away and finally felt a bit better.”

By this time, Fazal had come over. Making his way into the ruined house ones the fire had receded, he discovered his deceased youngest brother inside.

“He [Basith] worked at a phone shop. I used to scold him, telling him to work more and work harder. I just wanted what was best for him, but didn’t know that he was already doing a lot. Once he passed away, I learnt that he had been helping to teach 15 orphans. Many more people came and told me stories of how he was always helping them.”

Samsudeen’s second son sustained severe burns. His hands are irreparably damaged.

Even now, Samsudeen can’t remember how he and his wife managed to escape unscathed.

Samsudeen and his wife are in their sixties. Both his surviving sons have families of their own. Fayaz is still recovering and cannot work. None of them have received psychosocial support from the government, nor have they sought it on their own. They are currently living with extended family, and are managing to feed themselves “thanks to everybody’s kindness.”

The home they were living in was rented by them, not their own. It is currently being rebuilt—but again, through private funding.

“If the government officials had just done their job, this wouldn’t have gone so far. Now, even if they give a million, it doesn’t really matter. Will my son come back to me? No.”

Cultivating Patience—The Akurana Mosque’s New Role

K.R Faiz Moulavi was alone in the mosque when he saw the mobs approach. Standing on the second floor where tall glass windows faced the road, he saw pockets of people make their way down lanes, and convene around shops before attacking them. A few rocks were directed at the mosque, but it was otherwise ignored.

It was evident that they were targeting livelihoods. They passed by people’s homes and made a direct beeline for the Muslim-owned shops,” the Moulavi said. “Everything happened ‘peacefully’ with no injuries. That would have caused larger problems, and these people were very clear in what they wanted: nothing large enough to cost lives and cause massive problems, but large enough to destroy the community’s income.”

This spurred the mosque to take on a more active role in the Muslim community’s personal lives—they now have courses focusing on societal values for children, and also deliver Friday sermons.

According to Faiz Moulavi, the mosque wasn’t silent during the period of riots either.

“Even while the mobs were on the roads, we were transmitting messages for our people [through the loudspeakers]. We urged them to remain indoors, to be patient, and to ask dua [to pray]. We kept things under control by stressing how important it is to be patient, throughout the ordeal,” he said.

However, people are still afraid. Parents are still afraid to send their children for religious classes. The mosque previously had 72 children who attended classes, but numbers have now dwindled to 55.

“It’s definitely affected them. The parents and children both are scared,” he said, adding that he now focuses a lot more on lessons teaching co-existence, respect, and patience.

“We try to teach them that no one is different, and we’re all one,” he added, gesturing towards the paused class. “See? Even the class isn’t segregated. We teach our boys and girls together.”

Moving Forward

M. Riyaldeen owns a building in Katugastota, which has been let out to a handful of businessman. The building was bombed, destroying his tenant’s wares as well. He tells us he’s still running around government offices trying to get a state engineer to evaluate and give an official estimate of the damages.

“Without this, we can’t apply for compensation. The damages are in millions, but we received just the initial Rs. 50,000 early on. And you won’t believe it, the Gramaseva came by recently and distributed leaflets saying that they’ll offer a loan of Rs. 10,00,000 for just 2% interest,” he said.

Riyaldeen comes from a mixed family; his father was Moor and his mother was Sinhala Buddhist. While his parents were alive, they were popular for being helpful around the neighbourhood. Both sides of his family are on cordial terms, and have no bad blood between them. He tells us that they are at a loss at how to react to the race-motivated violence.

“When my property was burned, my mother’s side of the family came to visit immediately. They offered what help they could, and were shocked as to why anyone would want to attack us. At times like that, it makes you realise that you can’t really even ‘scold’ a side. How can I get angry about Sinhala people attacking my properties when Sinhala people were also helping me out here? I never saw race being a factor in anything while growing up, and it’s still very difficult for me to just blame an entire community for what happened here,” he elaborated.

Most of the people we spoke to are desperately waiting for the government to compensate them adequately. They were not optimistic of it happening anytime soon, especially as payments for the victims affected by the Aluthgama racial riots in 2014 began in March this year.

Others, especially in Akurana, have accepted private funds and are in the process of rebuilding their mosques, homes, and shops.

Our coverage of the incident can be read here.

Image credits: Aisha Nazim/ Roar Media