Over the course of history, the world has seen countless pieces of its heritage vanish forever with no chance for recovery. Vast contingents of knowledge are continuously being lost- to the passage of time, to natural causes like disasters, insects and mould, and to acts of war and unrest. Every time a palm-leaf manuscript crumbles with age or a mob-driven fire consumes a center of learning, the world loses an irreplaceable part of its past.

The burning down of the Jaffna Library in the year 1981, during the explosion of ethnic unrest, is still spoken of as one of the most devastating losses of knowledge the country has seen. Often depicted as a tragedy for just Sri Lanka’s Tamil-speaking communities, the truth of the matter is that when those 97,000 books went up in flames, the whole of Sri Lanka lost a large chunk of its documented heritage.

This is partly why the Noolaham Foundation initiated the Noolaham Digital Library in the year 2005- as a way of ensuring that such a devastating loss will never happen again.

Rising From Ashes; The Noolaham Digital Library

The Noolaham digital Library is a ‘virtual library,’ an online open-access database of Tamil language documents, books, manuscripts, videos and photos. “Basically, we are digitally documenting, protecting and preserving the heritage of Sri Lanka’s Tamil-speaking communities,” says Kopinath Thillainathan, one of the founders of the digital library.

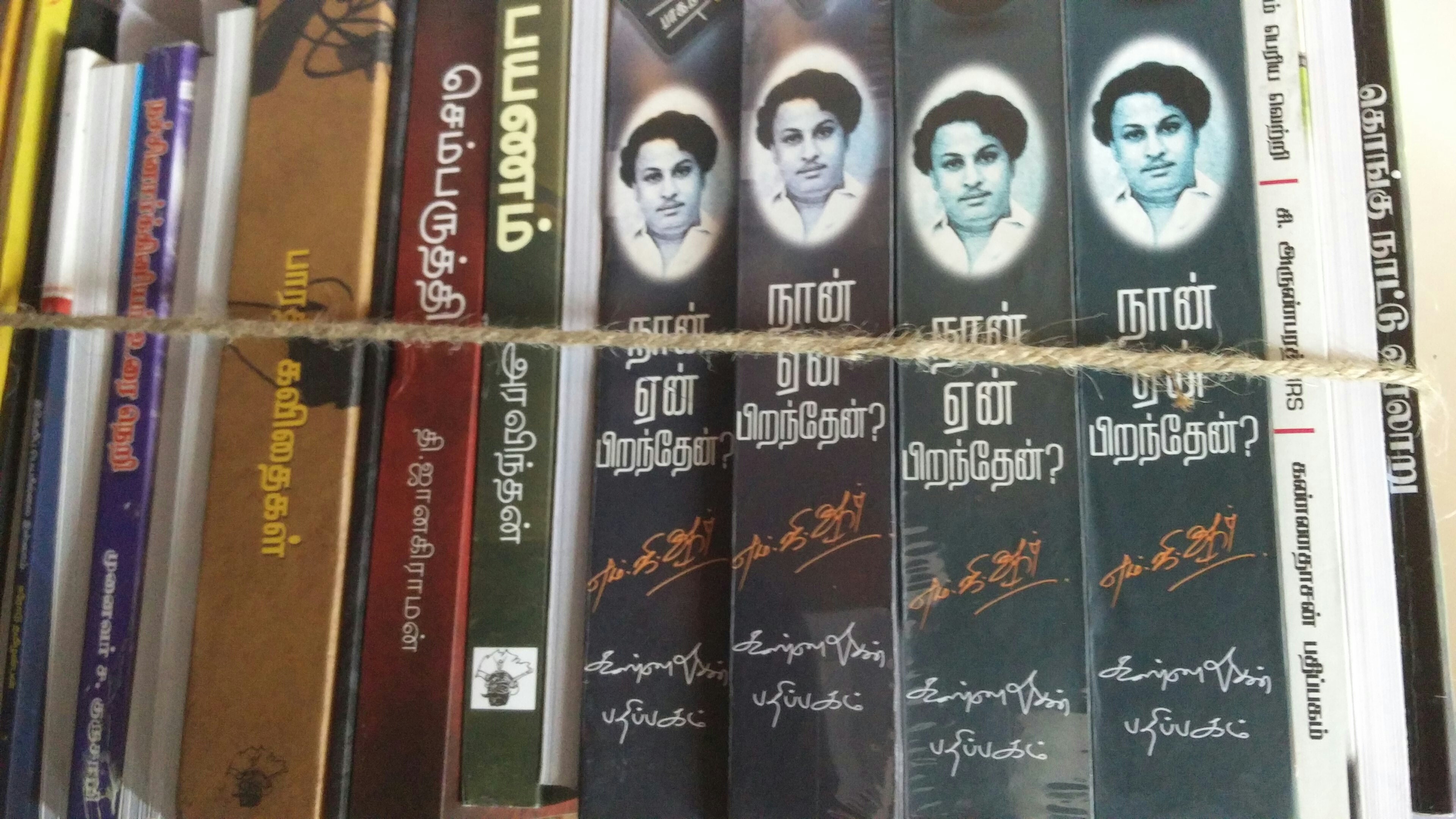

Thillainathan tells us that the greatest tragedy of the torched Jaffna library was the loss of those rare items which can never be replaced. These include palm-leaf manuscripts, around 140 years worth of newspaper editions (like The Morning Star, a bilingual newspaper which was started in 1841), handwritten manuscripts by reputed scholars, academics and poets, and rare editions of books which could not be found anywhere else.

Looking at these devastating losses, it is easy to see why Tamil speaking people from around the world rose to contribute towards the birth and growth of this digital library.

“While the Noolaham project took off in the year 2005, the concept of digitization had been around long before that,” says Thillainathan. Information technology had been growing in leaps and many individuals had been experimenting with small-scale digitization projects from as early as 1998. Noolaham is a culmination of all these smaller projects.

So What Would You Find In These Digital Archives?

“The library is multi-dimensional,” says Seran Sivananthmoorthy, one of the directors of the Noolaham Foundation. “We don’t just work with print anymore. We also have audio, images and videos.”

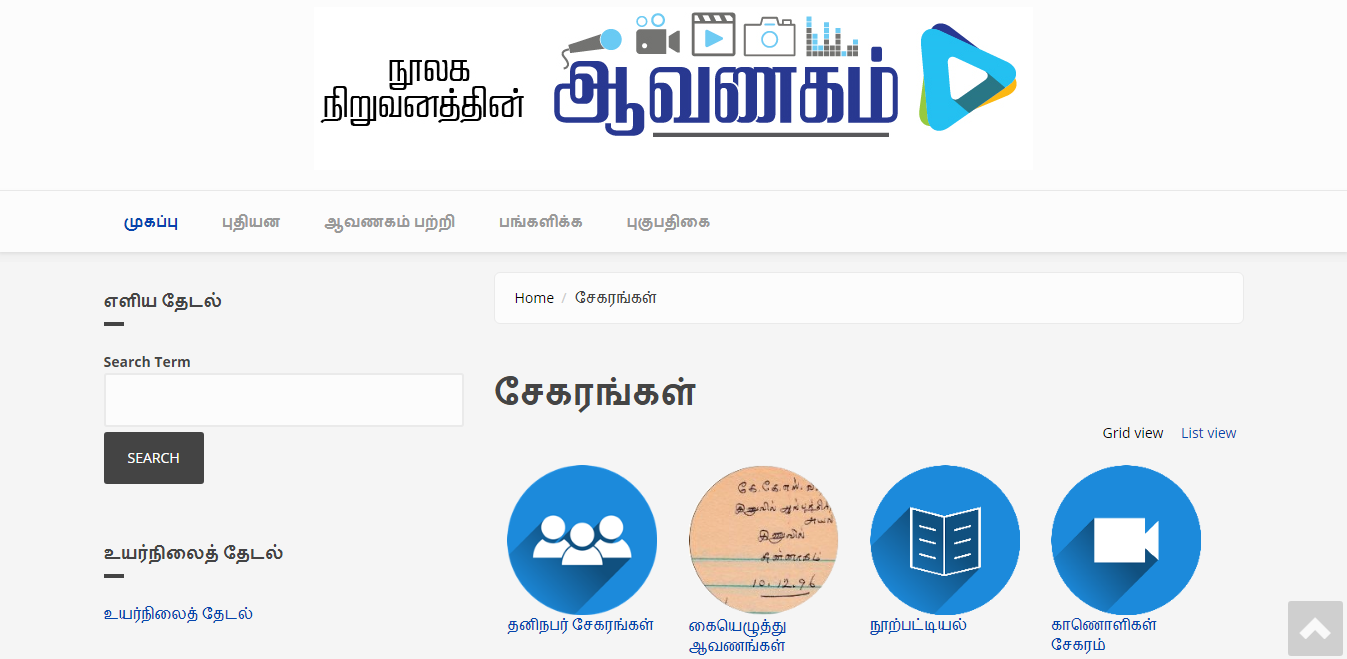

The digital repository consists mainly of two divisions, Noolaham, which archives print documents, and Aavanaham, which is a multimedia repository. Aavanaham archives born-digital documents, images, audio files and videos.

“We actually focus more on the multimedia than print now,” says Seran. “Times are changing, and the new generations seem to have completely moved into that sphere.”

The print archives now contain over 55,000 documents (including 7000 books and 35,000 newspapers), while the multimedia archives, which got off the ground much later, contain around 5000 items (including 3400 images and 900 ephemera). One of the most interesting initiatives in the works is the Oral History Project, a collection of interviews with a diverse range of individuals about their lives. They have so far archived the stories of over a hundred and fifty people from teachers and musicians to farmers and craftsman. Other projects included a Muslim Archive and the Malaiyaham Archive (which documents the culture and heritage of the Sri Lankan Muslims and up-country Tamils respectively), and a Women’s Archive which focuses on women and gender issues.

Of Ola Leaves And DSLR Cameras; How The Digitizing Is Done

“When we first started out, we used to type the texts,” says Thillainathan.. “One person would read out loud, while another typed.” Progress was slow and tedious, and in one year, they only managed to digitize about a hundred books. But as time advanced, so did the technology and they gradually moved onto scanners.

They currently use three methods of digitizing. Flatbed scanners are used to scan the rarer books page by page. Sheetfed scanners are used for books which have plenty of copies in existence, so the pages can be removed and fed into the scanner in bulk. However, for the more easily damaged documents like the ola leaves, cameras are used.

“Ola leaf manuscripts are very fragile; you can’t just feed them into a scanner,” explains Seran. To digitally archive them, he tells us, they use a specialized method using DSLR cameras and lighting following the British Library standards.

Nearly 75% of the digitizing is done in Jaffna, where most of the equipment is, though the Noolaham Foundation has offices in many locations including Colombo, Malaiyaham and Akkaraipattu. They also have what they call ‘chapters’ around the world – small branches in countries like Norway, America, Canada and Australia, which collect books for digitization, raise funds and spread awareness.

Why Digitize?

“Our Tamil-speaking people are scattered around the world and we want them all to be able to benefit from this,” says Thillainathan. “Going digital is the most efficient way of reaching the masses.” The palm leaf manuscripts for instance, which would have been nearly impossible to access, are now open to anyone from anywhere in the world.

Apart from the most prominent reason—the preservation and protection of knowledge— there is also the fact that this is the more cost-effective method of archiving and sharing documents as opposed to building physical libraries.

People also embraced this concept for sentimental reasons. Seran tells us that the Noolaham Digital Library is something of a community-driven project, with hundreds of volunteers and donors from across the globe contributing towards it since its inception. All the key members of the foundation make time for the project while also having their day jobs. Funds are difficult to come by – the Noolaham Foundation spends about five to seven million rupees a year on equipment, staff and other expenses. Nearly 90% of funds are obtained from donors or diaspora organizations, while only about 10% is supplemented from other institutions. The ola leaf archives, for instance, were funded by the British Library. However, the foundation has persevered over the years and still continues to grow.

“We are proud of what we have achieved,” says Seran, adding with a laugh, “But there is still more to do. We still feel like we have miles to go before we sleep.”

Cover image courtesy: wikimedia.org

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article mistakenly stated that the Noolaham Digital Library was initiated in 2010. This has been corrected to 2005.