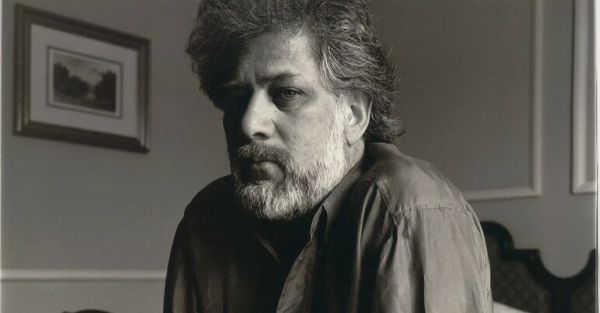

As a young boy of ten in the remote village of Vankalai, Mannar, Professor Augustine Sosai would hear the sounds of dynamites detonating out at sea. He knew what it meant — fishermen from the neighbouring villages were using explosives to illegally catch indiscriminate numbers of fish. “I’m 65 years old now,” he tells us. “When I am back at home in my village, I still hear dynamite explosions in the area. Nothing has changed for more than 50 years.”

Prof. Sosai is telling us about blast fishing, an activity which involves fishermen using dynamite to stun or kill fish, which can then be easily collected. This is one of the many IUU (Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated) methods of fishing that are practised in Sri Lanka. Prof. Sosai, who is associated with the University of Jaffna, has spent years researching and advocating for their eradication, but to little avail.

IUU fishing is a major global fisheries issue that threatens the sustainability of the world’s oceans. It can be defined as any fishing activity which is non-compliant with national, regional or international conventions or management measures. According to many officials and independent researchers Roar Media spoke to, the issue is quite prevalent in Sri Lanka’s north and northwest, where the waters are shallower and there is lesser policing by authorities.

In spite of being illegal, destructive fishing activities continue to take place. In fact, the situation reached the point where the EU imposed a ban on all fisheries exports from Sri Lanka in January 2015, severely crippling the fisheries industry for more than one-and-a-half years while the ban lasted. Here are some of the destructive fishing activities which are decimating our oceans, their socioeconomic and environmental impact, and why they continue to prevail in spite of the laws put in place to prevent them.

Destructive Fishing Activities Which Put Seafood On Your Dinner Plate

Blast Fishing

A few sticks of dynamite, a handful of unscrupulous fishermen and mere seconds is all it takes for hundreds of fish and large areas of coral reef to be completely destroyed.

Most fishermen turn to blast fishing because it is viewed as a quick and cheap method of catching large numbers of fish. According to Prof. Sosai, a stick of dynamite, along with the detonator, costs just Rs 1,000. However, it is unsustainable and highly detrimental to the marine environment, small-scale fishermen, and even the perpetrators themselves. “Just about a week ago, some fishermen here in Mannar were injured when a dynamite went off on a fishing trip,” Prof. Sosai tells us. “One of them lost an eye, another lost a hand, and the others acquired various other injuries.”

Blast fishing results in large amounts of by-catch, a term used to describe the non-target marine creatures, which are incidentally caught along with the target fish. A dynamite is not selective—it stuns or destroys everything in its blast range—and juvenile fish, turtles, dolphins, and even dugongs are often killed this way.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Arjan Rajasuriya, in his lecture on coral reefs in the North, spoke of a horrifying incident where a whole school of about 50 dolphins was once targeted in a dynamite blast. In another incident in 2010, two large dugongs were killed in Mannar; one of them was later discovered to be carrying an embryo. Rajasuriya also mentioned that modern technology like GPS and cell phones makes blast fishing—and getting away with it—very easy. Fishermen can easily pinpoint the location of shoals of fish, and warn each other of raids.

Blast fishing can also result in the destruction of coral reefs, biodiversity hotspots which support countless species of marine organisms. The damage done to coral reefs can take decades to reconstruct — certain massive corals only grow about 0.2 to 1 cm per a year.

Stake-Net (jakotu) Fishing

Near the coral reefs of Vankalai and Arippu, Prof. Sosai tells us about a village called Panangkattikottu (in Mannar District) which has been given permission by the Ministry of Fisheries to install stake-nets, or jakottu dal. Apart from this specific area, the method appears to be prevalent in other areas in Mannar as well. Rajasuriya, in his IUCN lecture, describes this as a passive form of fishing. Stake nets are fish traps: the nets stand in the ocean everyday, affixed to sharp metal stakes which are driven into the ocean floor, and are placed across the migratory paths taken by the target fish. Traditionally, this method was only used with wooden stakes and restricted to the shallower waters or the lagoon, but now the nets are large-scale, and used without restrictions.

“Now there are 37 villages in this area, but only one village has been licenced to do this,” Prof. Sosai says , speaking about this specific place in Panangkaddikottu. “Other small-scale drift net and beach seine fishermen find it difficult to fish. Their nets can get damaged, and they can never go out at night. The metal stakes damage the coral reefs when they are driven into the ground. Many other marine creatures like turtles are also caught.” Several small-scale fishermen recently travelled to Colombo to hold a discussion with the Department of Fisheries and NARA and protest against these fishing techniques, insisting that they are ecologically and economically unviable.

Lalith Ekanayake, one of Sri Lanka’s foremost turtle biologists tell us that many turtles get caught in these stake nets, as well as other types of nets like the purse seine, and gill nets. “When the turtles get caught in the nets, they struggle to get free, and in the process, they damage the nets,” he tells us. “Fishermen often get angry when they see the damaged nets, since they are very expensive. Sometimes, they just use a harpoon and chop off their heads. If they get caught in ray nets which are below the surface, they suffocate and die.”

Thushan Kapurusinghe, another turtle expert who is currently overseeing projects in the North, tells us that turtles are often kept alive inside these stake-nets for long periods of time. “This way, the meat stays fresh,” he explains. “Sometimes, fishermen capture the turtles elsewhere and then keep them in these nets for meat. If the Navy finds them, they simply say that the turtles had accidentally got caught.” According to Kapurusinghe, the Navy does not have the capacity to survey all nets, so the turtle meat racket continues to exist, even though it has lessened considerably.

Why Are These Issues So Prevalent In The North?

The amended Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Act of 1996 bans many destructive methods of fishing such as the harpooning of marine mammals, the use of improvised fishing gear such as metal rods and monofilament nets (thangus del), and the use of stupefying substances such as dynamite. So why does this continue to happen? And why is the north and northwestern region so prone to this?

British fish biologist Dr Steve Creech tells us that part of the reason why IUU fishing is so prevalent in the north and northwestern waters is due to the shallow nature of the sea. “Those areas, like the Palk Bay and the Gulf of Mannar, are really shallow and the continental shelf is very broad there,” he explains. “Most of these destructive fishing activities like trawling work better in shallow waters.”

Kapurusinghe tells us that the law enforcement is not always present in certain remote areas in the North. About the turtle meat racket, for instance, he says, “If someone sees people selling turtle meat in, say, Tangalle, and if they dial 119, the Navy can be there within minutes. In more isolated areas, the police or the Navy can take hours to get there.”

Kapurusinghe is currently working on a community livelihood project in the North, which aims to offer people alternative livelihood options in place of destructive fishing activities like blast fishing. He opens up a different argument about why fishermen continue to use destructive fishing methods. “Most people were struggling to make a living after the war,” he explains, telling us how many of them struggled with poverty, and hence turned to destructive fishing in order to feed their families. “That is why my initiative focuses on training [perpetrators] as tourist guides, or helping them earn a living by breeding ornamental fish.”

Euman Pranandu, the president of the Puttalam Fishermen’s Cooperative tells Roar Media, “We do use thangus dal [monofilament nets] for fishing, and it is illegal, but we need to survive and take care of our families. We buy these nets because they are cheaper and easier to get. We cannot afford big boats with motors.”

However, N. M. Aalam, the former president of the Fishermen’s Cooperative in Mannar, counters that claim by saying that destructive fishing activities are destroying Sri Lanka’s oceans. “There are less fish in the sea now,” he says. “Everyone needs to earn a living, but they need to do it within the law.”